You Saw the Beauty of Nature in This Town

The Levin-Ha'levi Family

Origin >> the Shtetl of Luninietz >> Aliyah to Eretz Israel >> Shchunat Maccabi

The Levin Clan, 1945

Top row, from right: Dov, Yankale, Bella, Sara (Arieh's wife). Isaac, Yaffa, Zalman

First row, from right, the patriarch, Yitzhak, the matriarch, Esther Malca, holding her first grandson Shlomo (Shyomic), Arieh, and Tzvi

The Dream

Esther Malca was known for her dreams and psychic intuition. Or maybe, this was her ingenious way to help the cause, any cause! In an interview with her son, Tzvi Levin in 2009, he reported the following: One early morning, in February 1934 Esther Malca was awoken by a nightmare. In the dream her Grandmother, Zlata, appeared and urgently told her to pack all their belonging and move to Eretz Israel. She informed her that danger is looming in Luninietz. The whole town will be destroyed and burned to the ground and all the Jews will be killed.

Esther Malca's other son, Dov Levin, recapped, "the dream," in his memoir, a bit differently. He wrote that on the Shabbat morning, after the dream, Esther Malca told them that her grandfather Arya Leib appeared in the dream, wearing a long soft white beard. Using authoritative gesture and a commending voice, he told her, Esther Malca, the ground here is going to shake and burn. Liquidate everything, take the kids and run away from here. Trembled and scared, she awakened and immediately woke her husband, Yitzhak, telling him about the dream. He dismissed it by saying, “here we go again.”

It took some convincing, diplomacy and lots of political maneuvering, nevertheless, in early October 1934 the family liquidated all their assets, paid their debts and departed Luninietz via a train to Lviv (Lvov) Ukraine. (only Arieh, the eldest son, because he was close to the military draft, stayed behind. After ten months he was able to get a visa and reunite with the Levin family in Palestine).

After spending couple of days in Lviv, the Levin family continued to the Port of Constanța, on the western coast of the Black Sea, where they boarded the ship SS Polonia (see a travel ad Picture 1) and began their voyage from Constanţa, via Istanbul and Pireaus, arriving in Jaffa Port on November 25, 1934.

The below Passport picture was taken in 1934. Apparently, at the same photo session more pictures were taken. A different image was chosen for the actual passport on the right.

The Levin-Ha'levi Family of Origin

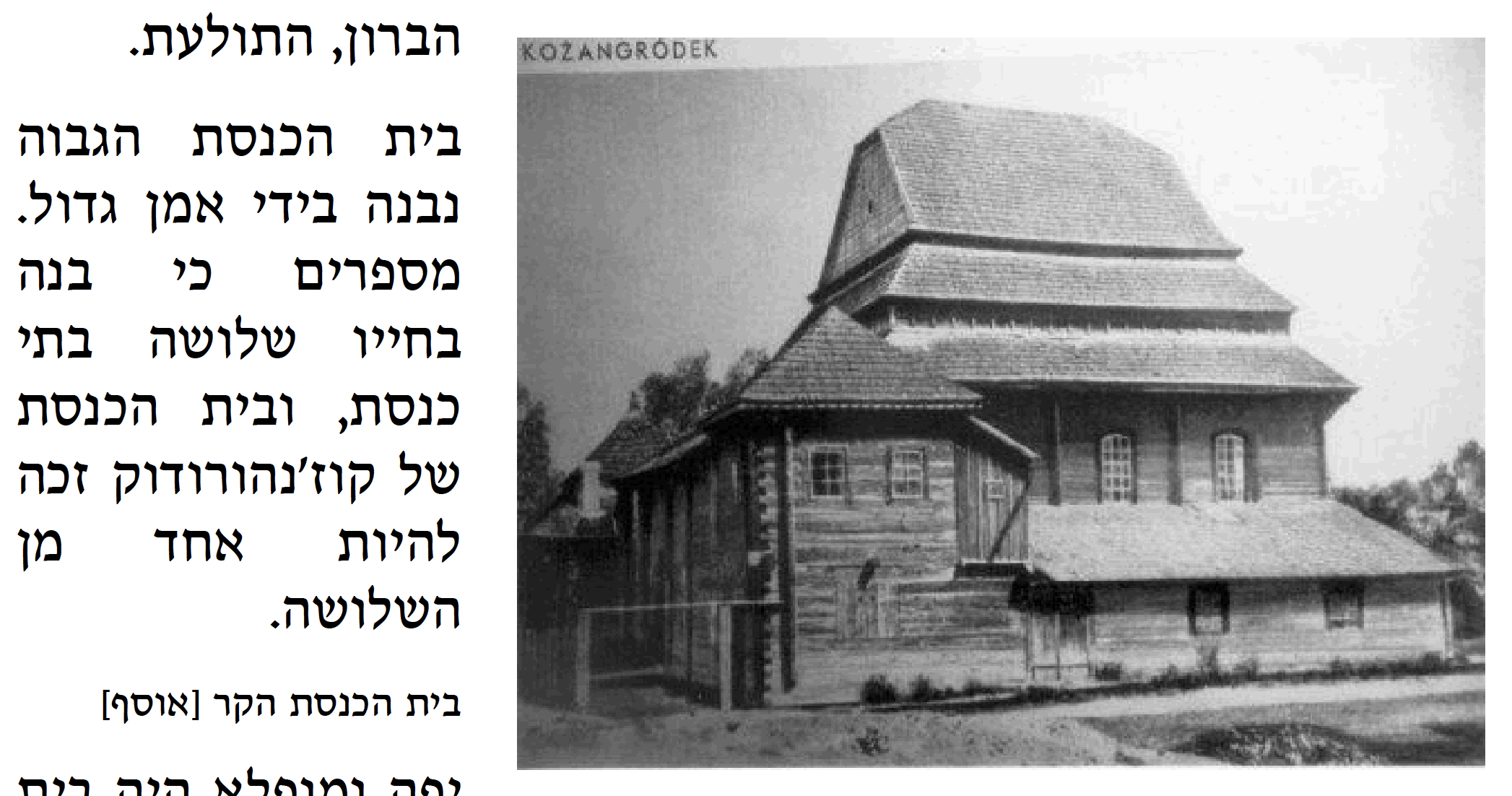

The Ha-Levi, Levin(e) family settled along the Pripyat river in an area of swamps and dense forests at the southern part of White Russia. The first known Levin(e), Moshe Yaacov Ha-Levi was born in 1835 (the below picture is of his son Shlomo born in 1865), in the shtetl of Kozhanorodok (the name may be transliterated in various other ways, including Kozhan Gorodok, Kozhanhorodock, Kazhan-Haradok, Kozhan-Grudek, Kazhaneradok, Kozhangrudek, Kurzanhradek). The town is located on the bank of the Tsna River, 2 miles from its confluence with the Pripyat River, in the Minsk gubernia, Pinsk uyezd and in the Kozhangorodetskaya volost, within the boundary of the Pale of Settlements – Today White Russia is known as Belarus. Over time, this territory belonged to various countries. Between the 16th-18th centuries it was part of the region of Poland until the second partition of Poland in 1793 when it became the Russian rule. In 1920 it moved into the Second Polish Republic.

Between the thick virgin forests and swamps of Pinsk, 9 miles west of Kozhanorodok, where a primitive majesty hovered, dwelled an out of the way hamlet called Luninietz (the name may be transliterated in various other ways, Luninyets, Luniniets, Luniniec). The hamlet was inhabited by uneducated White Russian peasants, submerged in ignorance and wretched poverty, not even one Jewish family resided at this castaway. Suddenly, the hamlet was awakened from its deep sleep. Rumors were heard of the laying down of railroad tracks. In the late 1880s, some of the Levin(e) descendants moved from Kozhanorodok to Luninietz to seek a source of livelihood.

Shlomo, Ben Moshe Yaacov Ha'levi-Levin 1865-1936. He was the Father of Yitzhak Levin – Bella's father

LUNINIETZ

Visit of the Rebbe or Admor Patshnik in Luninietz. On the left Shlomo Levin and on the right, his son, Yitzhak Levin. Yizkor Book, page 142

Luninietz and Kozanhorodok

“There was a section of Luninietz, near the forest, that provided freshness and light,” wrote Zehava Shocat, in her page of memoir, I’ll Not Forget You, Luninietz from The Jews of Luninietz and Kozanhorodok Yizkor Book (translated by Albert Latucha). She continues, “When you went out on a summer day to breathe fresh air and enjoy the sunlight, on the way to the forest, the sand hill, green fields and fragrant pine trees, you saw the beauty of nature in this town.” (page 80)

Asher Plothik wrote about “The Development of Luninyets” in the Memorial Book for the communities of Luninietz and Kozanhorodok Yizkor Book (pages 17-19). “At the beginning of the twentieth century Luninyets was still very young. The town was built on a large level field, surrounded by forests of pine trees. To the North-West there was an extended marshland, where many birch trees grew, as well as other trees and shrubs that served as burning-wood. In the winter, the peasants would chop the trees and bring them to town on sleighs, during the rest of the year no person would set foot in this marsh area. To the East and to the South, sands and also black fertile soil extended to the horizon, and when the town grew in size and in population these soils were transformed into cultivated fields, growing wheat and potatoes. The place was not blessed with a river or streams; therefore, a large settlement has not developed there.

At the beginning, only very few peasant families, poor and destitute, lived there. Only when the railroad tracks were constructed in the vicinity, the town became awake and an enormous movement of construction began.”

Memorial book of Luniniec and Kozanhorodok Yizkor Book Edited by Yosef Zeevi (Wilk) et al. Published by the Association of Former Residents of Luniniec / Kozhanhorodok in Israel, Tel Aviv, 1952. This chapter was translated by Lou Keller. (page 207-209)

According to Max Schneiderman My Youth account (Pages 207-209), “the old people told us that according to plans, the railroad was supposed to run through Kozanhorodok. For that to happen an officer had to be bribed. Unfortunately, the high sum demanded was beyond the means of the town. Kozanhorodok remained without a train.

The shoemakers, tailors and carpenters moved to Luninets to find income. The remaining poor folk lived off each other, the goyim and surrounding villages. Here were fairs four times a year. Two in winter and two in summer.

The population of Luninets consisted of farmers that used to travel to Kozanhorodok to sell their farm products and to purchase the necessary wares, fabrics and tools. Only in the 70’s of the 19th century, when they began to build the Homel-Brisk rail tracks near Luninets and started to erect the railroad station did the Jews from Kozanhorodok appear. They were artisans and merchants that earned money from the train workers. Jews, however, according to the laws of the Pale of Settlement could not settle in the town. They couldn’t even sleep over.

Every evening they had to return to Kozanhorodok. Life was tough, but what doesn’t a Jew do to earn a livelihood? A greater tide of migration into Luninets occurred years later when the Baranowitsh-Sarne line passed the own, and the large train bridge, over the Pripet River began to be built. Due to the huge marshes, several thousand workers were employed and the project dragged on for several years. The laborers were good customers. Not only did Jews arrive from Kozanhorodok but also from Lachva, David Horodok and even from Pinsk. But they were prohibited from living in Luninets.

As told by the elders of Pinsk, the engineers who built the Baranowitsh-Sarne line made an offer to the Jews of Pinsk. For a large sum of money, the engineers would run the rail line through Pinsk and not Luninets and thus make Pinsk a rail hub.

The Pinsk Jews felt that if there was a plan to run the line through Pinsk it would happen without the bribe. They could not believe that Luninets and not Pinsk would be a railroad hub. The line passed through Luninets as foretold by the engineers.

From then on Jews settled in Luninets ignoring the law [As noted before, some of the Levin moved to Luninets in the late 1880s EH]. The Jews suffered greatly at the hands of the Czarist police. They had to bribe, to remain in town. At that time, Luninets had neither a Bit Medrosh; [literally a ‘house of study ‘. It was that, but it also served as a house of prayer on weekdays LK] nor a cemetery. The dead had to be buried in Kozanhorodok.

This scene repeated itself, whenever large railroad stations were built near villages where Jews were not allowed to reside.

Unable to stop the Jews from settling near stations, the Czarist regime issued a special statute according to which 109 villages, including Luninets, residing in the domain of the Pale of Settlement, were recognized as Pasadn, where Jews were allowed to dwell. [cannot find the word Pasad – must be area – could come from the Polish word pas or pasek which means belt – a subscribed circled area LK]

The Jewish settlement was beginning to grow. Houses were being built, also three “beit midrashim” and bath [mikveh]. The cemetery was laid out.

All of this was happened at the sacrifice [on the account] of Kozanhorodok which was shrinking from year to year. The artisans and merchants moved to Luninets. Kozanhorodok emptied and remained deserted.

Since all the land in Luninets belonged to the peasant organization, the Jews as well as the Christian non-peasants, had to lease the land on which to build their houses. The lease had to be renewed every 12 years. That was an expensive proposition. The peasant owners had to be bribed with a bottle of whiskey at every lease renewal.

That did not faze the Jews, and the settlement continued to grow. In the First World War, in the fall of 1915, the Germans captured Pinsk. Luninets was in turmoil. The richer Jews left Luninets and rode deeper into Russia. The front however remained at the Yaselde River, 40 km from Luninets. The enemy did not reach Luninets. His planes, however, reached the town and dropped bombs. Many refugees arrived from German occupied territories. A Jewish committee was formed, that provided the refugees with food, dwelling and clothing. Even after the war Luninets had much to endure. The so-called Officer’s League, of the Russian and then Polish army, occupied the town.

Eventually, after the Riga Treaty, Luninets remained part of Poland. Normal life returned. Luninets became a district capital.”

Most of the Jews lived in the center of town, where they had workshops and shops. Some were trading and some were craftsmen such as tailors and shoemakers. With the establishment of the Jewish community in Luninitz, many, especially builders, found their livelihood there. The town was rich in fish, and the Jews also engaged in fishing and fish trade.

[A comment on the designation by the Russians of towns and villages. Jews were not allowed to live in cities, because they would be too close to government and its secrets. Near churches, because they were anti-Christ etc. However, when they needed money, they would change a town where Jews were permitted to dwell into a village they were not or vice versa and give them (the Jews) a choice between moving out or paying an extra penalty. Shalom – Lou]

The Economic Life

The Jewish Storekeepers, artisans, small merchants and workers in Luninets drew most of their income from the peasants, railroad workers and government employees.

The latter benefited from very liberal credit arrangements.

The relations between the Jews and Christian communities were good. The Jew was the stable outlet for the products of the peasants, as well as the employer of many Christians in the forest holdings.

The Jews of Luninietz were engaged in trade and crafts. The train station was an important source of livelihood and the Jews who worked there were organized by a trade union established in 1905 and members of the Bund. Among the craftsmen were blacksmiths, tinsmiths, and rattlers; A tailor's cooperative, a butchers 'union and a merchants' organization were formed.

The economic situation worsened in the 1930s, when the Polish government declared the “owshem” (“our own”) policy – an economic boycott against the Jewish products and workers. With the help of the government, Poles penetrated all sectors of the economy and pushed the Jews away from them

The artisans and storekeepers carried on a bitter struggle against the destructive policies of the government and its institutions. In the last years, the propaganda and boycotts against the Jewish businessmen and workers broadened and became more organized.

Christians opened private and co-operative stores, and with government guidance established clothing and footwear workshops. That, plus the import of ready-made (ready to wear) goods, forced many Jewish tailors and shoemakers to close their stores. In spite of the relief offered by the Jewish co-operative banks, the exit of the Jews from their businesses continued.

Before World War II, there were about 3000 Jews in Luninitz, which constituted about a third of the city's inhabitants and in the town of Kuzhnhorodok about 100 – 150 Jews.

The Holocaust Period

One fate was for Kozhnhorodok and Luninietz in World War II; When the war broke out in 1939, the whole area was occupied by the Soviet army. The German invasion of the Soviet Union, the Jews attempted to flee from Luninietz to Russia, were arrested by the Red Army, and forced to return, only a few managed to cross the border.

In August 1941, almost all the men from Luninietz and Kuzhenhorodok were murdered; The children and women from both places were imprisoned in the ghetto. In August 1942, all ghetto residents were shot and murdered and buried in a mass grave. Over 50 individuals of the Levin family perished.

Jewish communities and individuals, such as the 10 family members of Yitzhak and Esther Malca Levin and one cousin Malca Orion nee Palach, who immigrated to Israel before World War II survived along with those who managed to escape to the Soviet Union or China during the war.

Enclosed a PDF file of Yizkor : Kehilot Luninietz and Koz'anhorodok

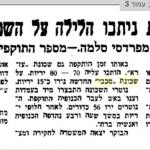

Luninietz Train Station, 1915

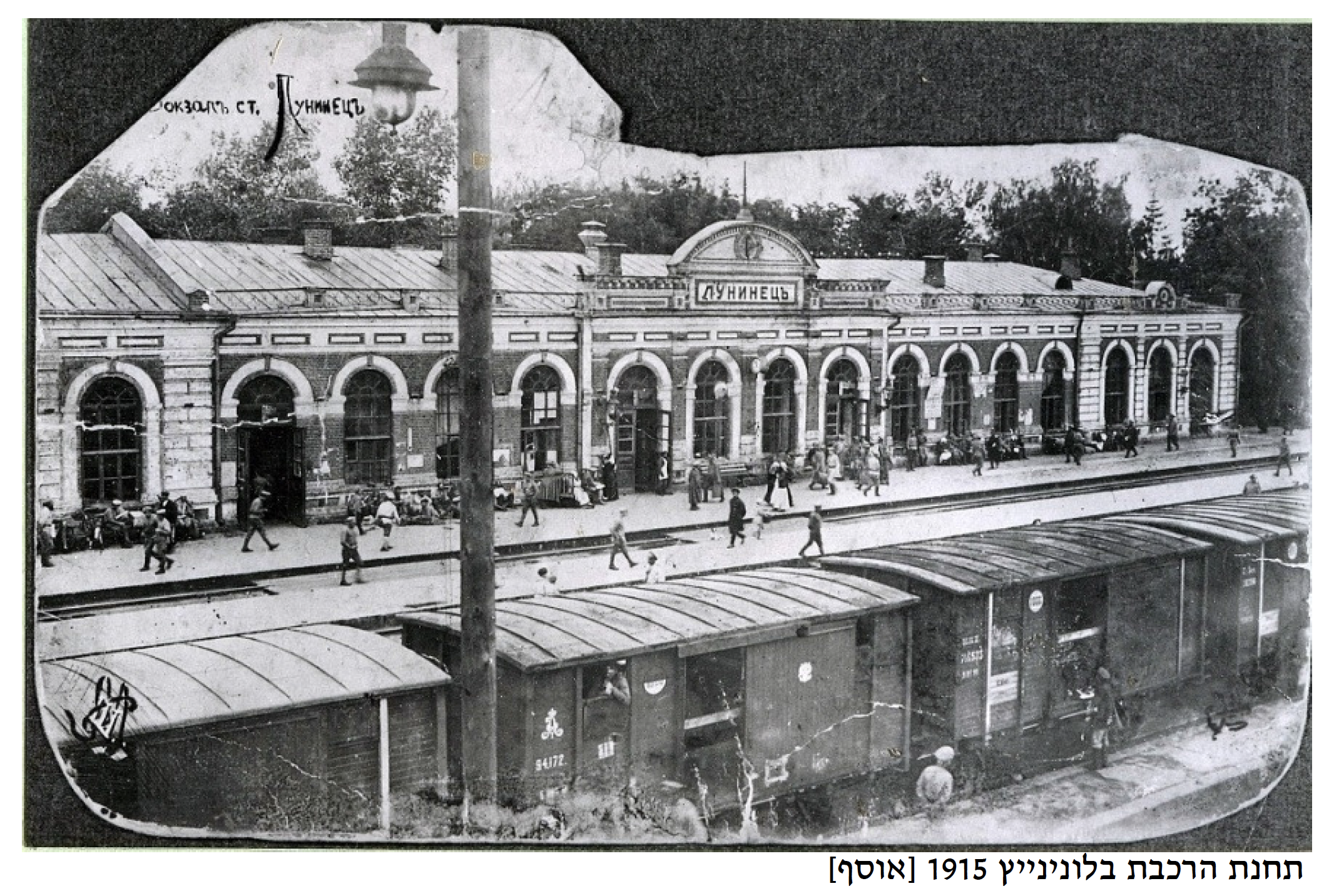

Fire Station in Luninietz, 1917. It used for gatherings and events

The Cross Street, one of the first streets in Luninietz

Listopada Street, were Jews and Gentiles Lived

Online courses

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

Kozanorodok H'kar Synagogue

Stalls in Luninietz Market, 1922

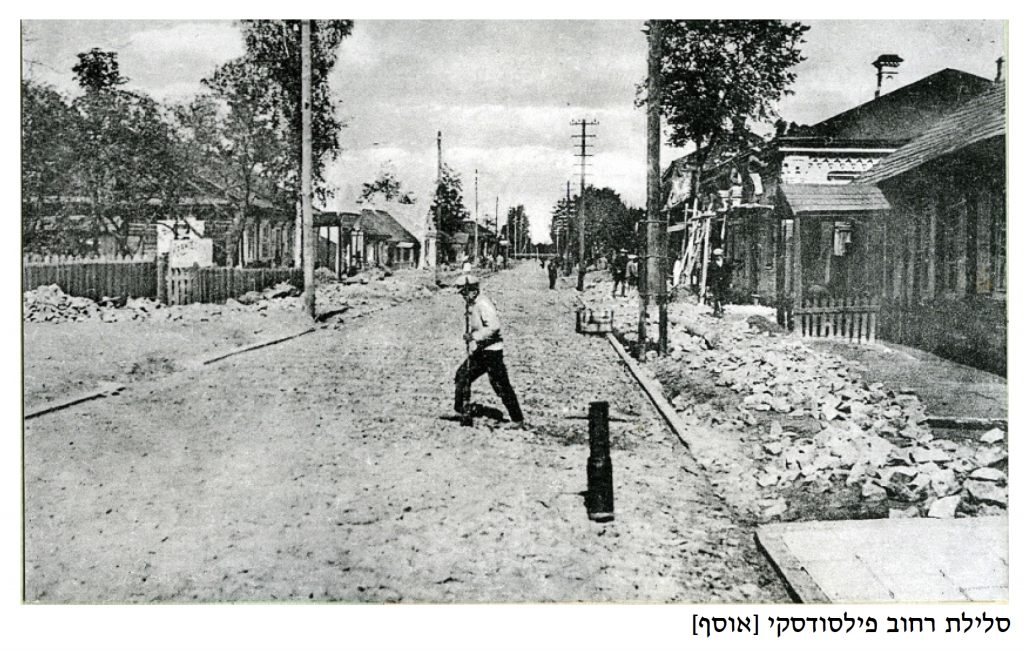

Pylsidasky Street paving

The tailor union in Luninietz, 1908

The Butcher Shops in Luninietz, 1936

consultation

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

Shchunat Maccabi

Shchunat Maccabi (Maccabi Neighborhood) History

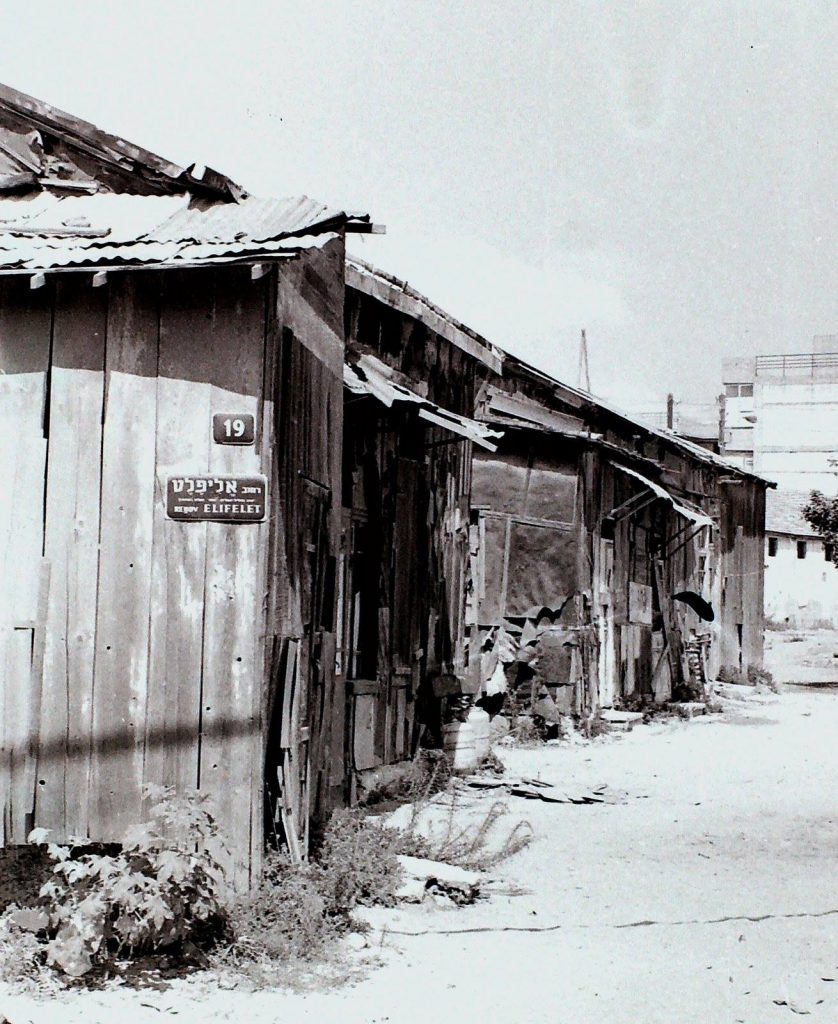

In 1925, fifty Jewish immigrant families, which formed the Maccabi Barracks Cooperative Association, purchased nine-and-a-half acres of land at the corner of Elifelet Streets and the Rebbe Mevarech Street of today (then, Amalican Street), in Jaffa and erected their barracks. The location, near the German American Colony and adjacent to Palm Court – the Maccabi football field, that was jointly used with Ha’poel Tel Aviv Association.

The poor immigrants lived in small, modest huts, made of wood with tin roofs. Most of the cabins were so small and shared a kitchen and a bathroom with adjacent huts. The neighborhood suffered from Arab riots in 1929, during “The Great Revolt” 1936-1939, and during the 1940s.

In 1936, the Levine family sought a place to house all ten members of the family. They bought a shack in the Maccabi neighborhood and over the next few years bought another shack. They quickly became part of a united and active community. In their home, weapons caches were hidden beneath the floors, behind the plywood of the flimsy hut’s walls. It is told that during a British authorities search for hidden weapons cache among the civilian population at Shchunat Maccabi, they searched the Levin's hut. Esther Malca positioned herself, atop the wooden floor and the entrance to the weapons cache. She didn't move until they left the hut and retrieved from the neighborhood.

At one end of the neighborhood stood a two-story building, which served as an observation tower for the British Mandate police. The purpose of the "tower" was to protect the Jewish neighborhood from Arab rioters. The British, themselves turned a blind eye and often allowed the Arabs to attack the neighborhood, responding slowly and ineffectively.

Above, Bella Hadar, in the Maccabi Neighborhood, 1946

Levin family's Hut, 1936. From Right, the mother, Esther Malca, Bella, the father, Yitzhak and Tzvi

Esther Malca and Yitzhak Levin with their first grandchild, Shlomo at their Hut yard, 1945

Levin Family with guests from Luninietz at their Hut, 1945

Tzvi Levin (right) and his brother Zalman

Shchunat Maccabi, 1975

Online courses

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

Bella (right) with her brother Arieh and sister Yaffa, circa 1939

Bella, circa 1947

Bella, circa 1945

Shchunat Maccabi, 1975

Workshops

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

The Levin family at the Palm Court, 1940

Soccer game (video) in the Palm Court – the Maccabi football field, that was jointly used with Ha’poel Tel Aviv Association, 1935. Courtesy, Israel National Archive

Yaffa at the Palm Court, Megrash Ha'poel

Bella at the Palm Court, Me'grash Ha'poel. Notice she wears the same outfit as her sister, Yaffa (above). The sisters did not only share a bed, they also shared their clothings

Shchunat Maccabi, 1975

consultation

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

Terrorist attack against Shchunat Maccabi and the surrounding areas 1938-1948, Newspaper clippings

Yaakov Levin, (Yankale) Saved Shchunat Maccabi from a Murderous Arab Mob

Arab rioters knew that most of the men in the Maccabi neighborhood left every morning, to go to work and only the kids, the women and the elderly stayed behind.

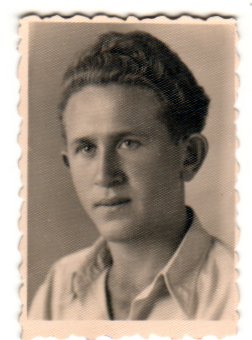

On a hot and humid summer afternoon in 1947, Arab mob began to move into the neighborhood. No one stood in its way. At the same time, Yankale, 20 years old (see picture) was at the Levin hut, dressed in undergarments. He was holding the wooden handle of a hot and heavy clothes pressing charcoal iron (see picture of the actual Iron). He was off duty that day, helping his dad, Yitzhak, in his garment business.

As soon as Yankale heard the mob approach and the screaming of neighbors, he didn't hesitate. He opened the weapons cache, hidden in the Levin family hut, took several stun grenades and ran towards the mob.

He threw the grenades, stopping the "invasion" and attempted destruction of the neighborhood as well as the massacre of all the Jewish families.

The Arab mob fled but on the way out, they informed the British guards that they were the victims. The British Police entered the neighborhood and started searching for the man who threw the stun grenades. They were looking for the guy wearing the undergarments.

Yankale, of course, had already returned to the hut, dressed up and walked around the neighborhood, like one of the guys.

Yaacov Levin

Yitzhak Levin, the tailor's coal iron

Yitzhak Levin, the tailor's scissors, 1934-1962

Correspondence (all in English) regarding a mortgage note for the Maccabi Cooperative Society Barracks neighborhood, October 31, 1942. The name of Yitzhak Levin, on the mortgage notes

PDF File, courtesy Israel State Archive

Nunc nec massa nec est interdum suscipit. Donec vel orci quis dolor

Image Sources: ארכיון משה ״פומי״ הדר

Reflection and Memories of Esther Malca by her Son Dov Levin

Dov Levin's Memoir

Gastronomia at the Levin's Home in Luninets

The Dream, the Aliyah and acclamation in Israel 1934-1939

The Levin Family Circle, United States, 1941