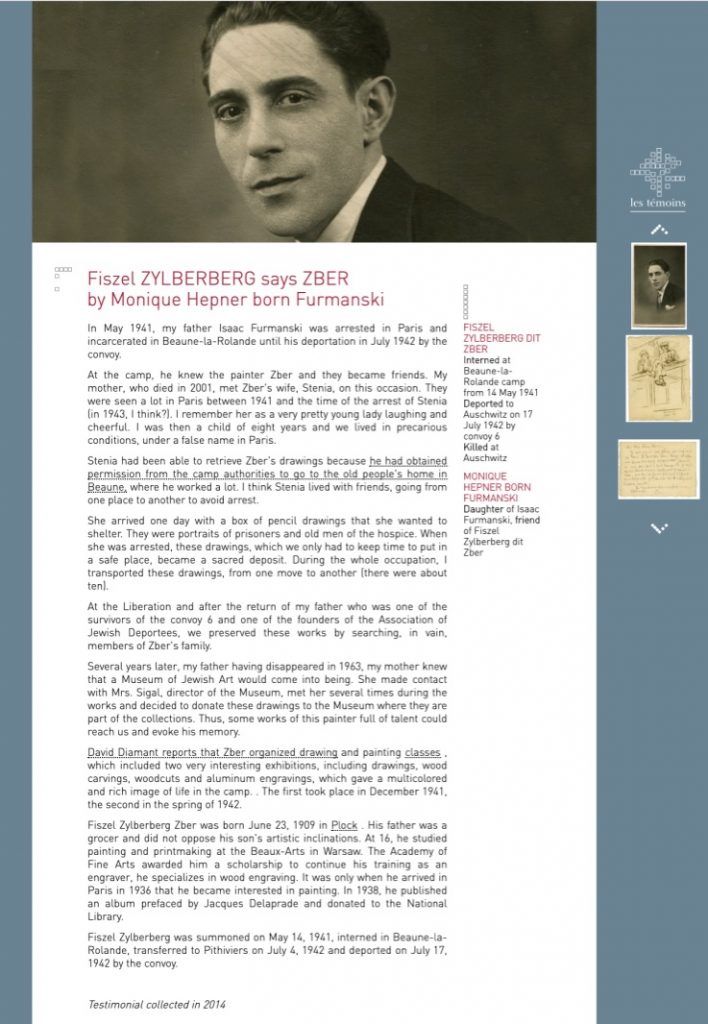

Fishel Zylberberg-Zber

1909-1942

Fishel Zylberberg-Zber was said to be a young artist who was a genius of the graphic arts, so much so that his style was known to have a "lyricism drawn from life itself." His masterpieces are now represented in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the Tel-Aviv Museum, the Museum of Modern art in Haifa, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and in many other reputable art museums.

Hailed as a “poet of his generation,” Zber's artwork encapsulated all that was around him. Whether it was the intimate nature around him, or the diligent workers doing their trade, his artwork was known to be authentic and true to reality, to the point where it is said to be palpable.

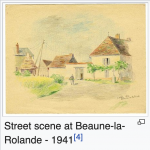

The genius graphic artist was arrested on May14, 1941. Along with the first 5,000 Parisian Jews, he was sent to the French internment concentration camp of Beaune-La-Rolande.

Zber was born on June 23, 1909 in the city of Plock, in the Warsaw district, on the Vistula river in central Poland. He was the son of Ruchlla Zylberberg nee Nordenberg was (born in 1887) and Wolf-Zelig Zylberberg. The couple had four sons and one daughter. The whole family, with the exception of one son who fled to Russia, were murdered in the Holocaust. Fischel Zylberberg-Zber was murdered in Auschwitz.

Aaron Pomerantz (Pommy’s father) was Ruchalla’s cousin.

Fragment of Bielska Street in Plock. Visible tenement house on the corner of Bielska and Szeroka (kwiatka), where Fishel lived with his family, Photo by Julius Klos, 1918 (collection of the Plock Scientific Society, reference # 363)

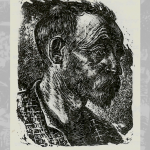

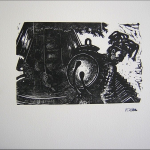

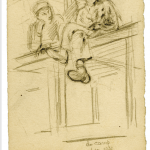

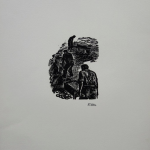

Fishel Zylberberg-Zber

Fishel Zylberberg-Zber

“It’s such a loss,” wrote, Eliyahu Eisenberg (1967), in the article, "With Fishel Zylberberg before his tragic death" – about the friendship of Isaac Formansky (later chairman of the Association of Former Nazi Prisoners in France) and Fishel.

Formansky said, "Although he is only one of the six million, but if he was alive, he could, through his artistic talent and human sensitivity, give the world a bitter weep, expressing the horrors of that horrible period and shaking the conscience and hearts!"

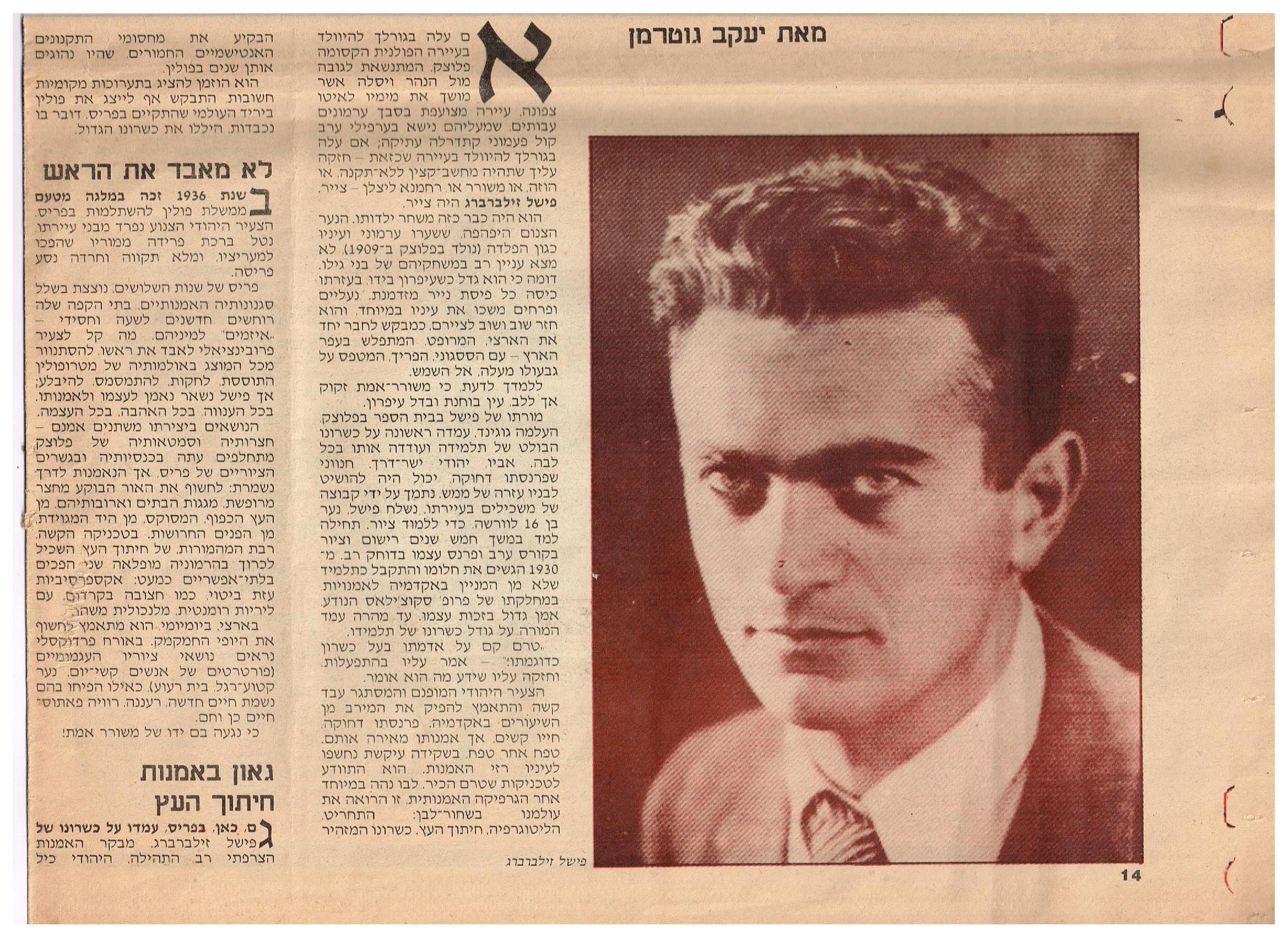

Zber by Jacob Guterman of Plock

Attached here is the English translation of the article published in Al Ha’Meshamar Newspaper on 25.07.1986

If your destiny was to be born in the magical Polish town of Plotsk (Plock), which rises high above the Vistula river, that slowly flows northward. A town shrouded by thick chestnut trees carrying, in the evening mist, the sound of an ancient cathedral bells. If it was your destiny to have graced this town – you must be a philosopher, a poet, or a God forbid – a painter. Fishel Zylberberg was a painter.

He was like that since childhood. The handsome slender boy, whose chestnut hair and steel eyes (born in Plock in 1909) found little interest in playing games with his peers. He seemed to grow up with a pencil in his hand with which he adorned every possible piece of paper. Predominantly, shoes and flowers attracted his eyes and he kept repeating them over and over again, as if trying to piece together the earthy, shabby, wallowing earth clay – with its colorful, crisp pursue. To the sun.

You must know. A true poet only needs a heart, an astute eye and a pencil stub.

Fishel's teacher at Plock's school, Miss Gogind was the first to discover her student's artistic brilliance and encouraged him wholeheartedly. His Jewish father, was known to be a man of integrity, a hardworking grocer who was struggling to make ends meet, and who could not provide his sons with any real help. At the age of 16, Zber moved to Warsaw with the intention of actively pursuing his artistic career. This was made possible by the financial support Zber received from the Jewish intellectuals in his hometown who believed in his artistic endeavors. For the first five years in Warsaw and as a way of earning income, Zber worked during the day at a picture postcard factory, and took private drawing and sketching lessons during his free time at night.

In 1930, he fulfilled his dream and was accepted as a full-time student at the Academy of Arts in the department of renowned Prof. Wladyslaw Skoczylas, a great artist in his own right. The teacher soon realized his student’s immense talent.

"Not as yet in our earth has risen such a talent!" He said with admiration and he knew, what he was talking about.

The introverted, self-confessed Jewish young man worked hard to make the most of the academy lessons. His livelihood is tight, his life is difficult, but his art enlightens them. Tap by tap. With his stubborn diligence, the fountains of art were revealed to him. He became acquainted with techniques; he was not yet familiar with. His heart was especially drawn to the graphic arts. The one that sees our world in black and white: the etching, lithography, wood cutting. His brilliant talent broke the strict anti-Semitic barriers and anti-Jewish laws that were so prevalent in Poland in those days.

He was invited to exhibit at important local exhibitions. He was also asked to represent Poland at the World Fair held in Paris. It speaks dignity. Praise his great talent.

Don't lose your head

In 1936, the Polish government awarded him an eight-month scholarship to study in Paris. The humble Jewish young man parted from his town, taking a farewell greeting from his parents, who became his fans and hopelessly and anxiously traveled to Paris.

Paris of the 1930s sparkled with many artistic images, its cafes sizzle with innovators of sorts. It was easy for a provincial young man to lose his head, to dazzle with everything in the lively metropolis' halls, to mimic, dissolve, and get swollen by the environment. But Fishel stayed true to himself and his art, with all the humility, love, and intensity.

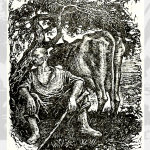

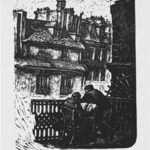

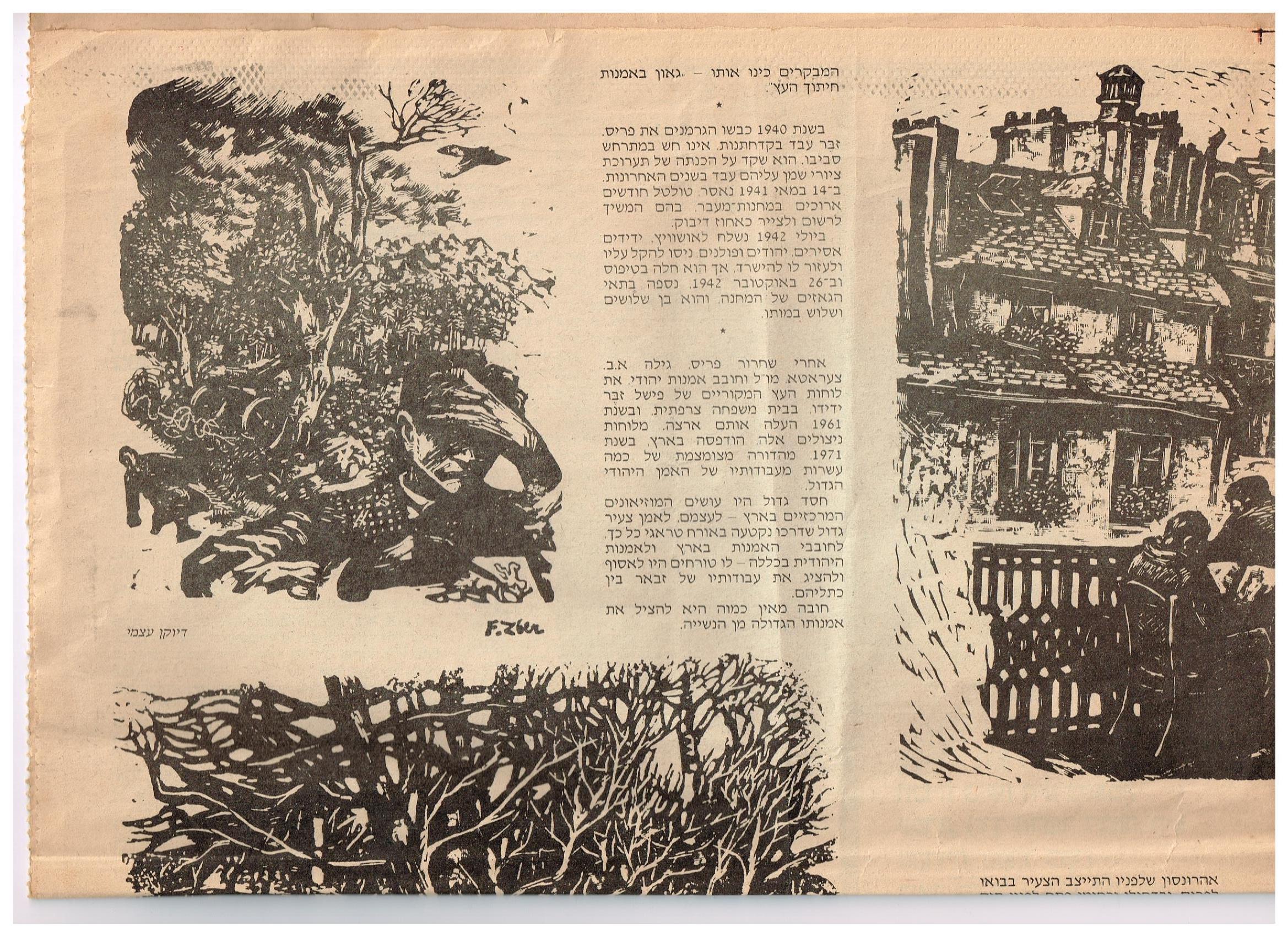

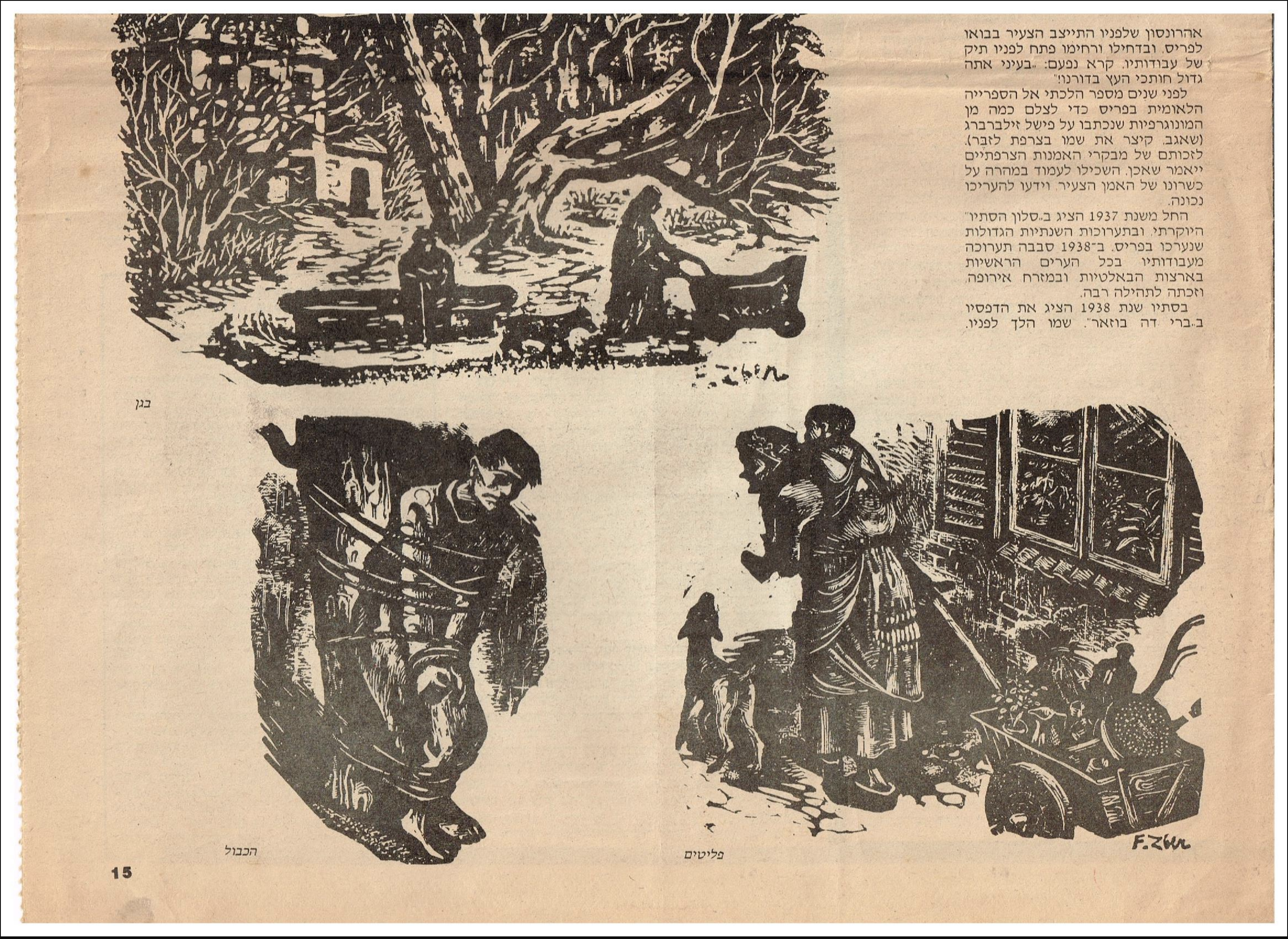

The themes of his work taking new subjects – Plock's courtyards and alleys are now replaced by the picturesque churches and bridges of Paris, but the loyalty to his artistic path is preserved: to expose the light emanating from a rickety courtyard, from the roof tops of houses and their chimneys, from the bent and gnarled wood, from the chapped hand and deep creased face. In the difficult technique of woodcutting, he was able to marvel in the two nearly impossible and oppositional harmonies: strong expression chiseled with somewhat melancholy romantic lyricism.

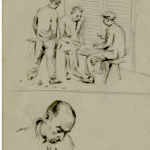

He strives to expose the elusive beauty. Paradoxically, the subjects of his mournful paintings (portraits of hard-working people, a broken-footed boy, a dilapidated house) look as if they have received new life, saturated with a warmth and pathos.

Because they were touched by the hand of a true poet!

A genius in the art of woodcuts

Paris was talking about Fishel Zylberberg’s talent. He presented himself and his art portfolio to the well-known French-Jewish art critic, Chil Aronson, who gave him much praise as a xylography protegee, exclaiming, "In my opinion, you are the great wood-cutter of our generation!"

A few years ago, I went to the National Library of Paris to photograph some of the monographs written on Fishel Zylberberg (who, incidentally, shortened his name to Zber). To the credit of the high-ranking Parisian critics, and graphic arts experts who wrote admiringly of him as a masterly young artist with a genius for wood engraving.

Beginning in 1937, he exhibited at the prestigious "Fall Salon" and at the major annual exhibitions held in Paris. In 1938, an exhibition of his works toured all the principal towns of the Baltic countries as well as Eastern Europe, which received great notoriety.

In the fall of 1938, the last exhibition of his career was showing his prints by the publishing firm of the Rue des Beaux Arts, followed by having his work published in a limited edition album, submitted to the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Critics called him "a genius in the art of cutting wood."

In 1940, the Germans occupied Paris. Zber worked frantically, not sensing what was going on around him. He has worked on the preparation of an oil painting exhibition, which he has been preparing for several years. [For some time in 1940 he escaped Paris with a group of about 10 Polish friends, but then decided to return to his beloved, Stania, an activist in the Nazi underground movement in France, whom he later married. See article later].

On May 14, 1941, Fishel was arrested and spent many months in internment concentration camp. Even under these horrendous conditions, he continued to pursue his artwork as though being possessed.

In July 1942 he was transferred to the Pithiviers camp, and the next day to

the Auschwitz extermination camp. Friends, Jewish and Polish inmates, tried to ease his condition and help him survive, but he fell ill and on October 26, 1942, he was murdered in the prime of his career in the camp's gas chambers. He was thirty-three years old.

[Although his career was short-lived, Zber’s artwork left an indelible mark that speaks to the life and conditions of early 20th century Europe, with great historical relevance].

After the liberation of Paris, A.B. Zarata, a publisher and a Jewish art aficionado, discovered 39 of the original woodcuts’ plates of his friend Zber at the home of French family, and in 1961 he brought them to Israel. A limited-edition album of several dozen of the works of Zber’s surviving woodcuts was published in 1971.

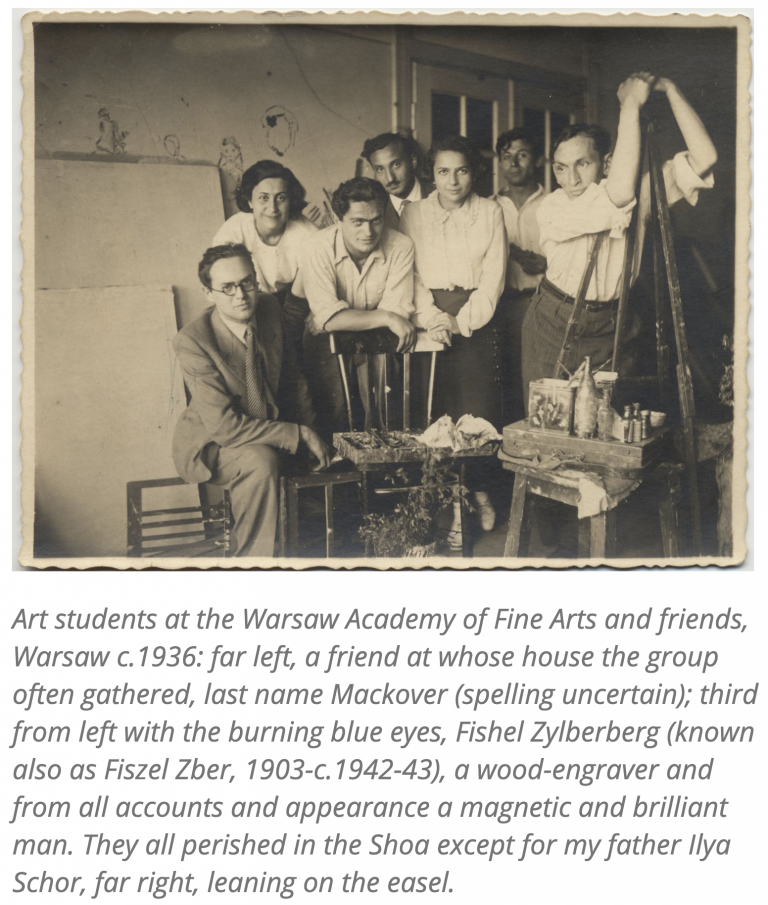

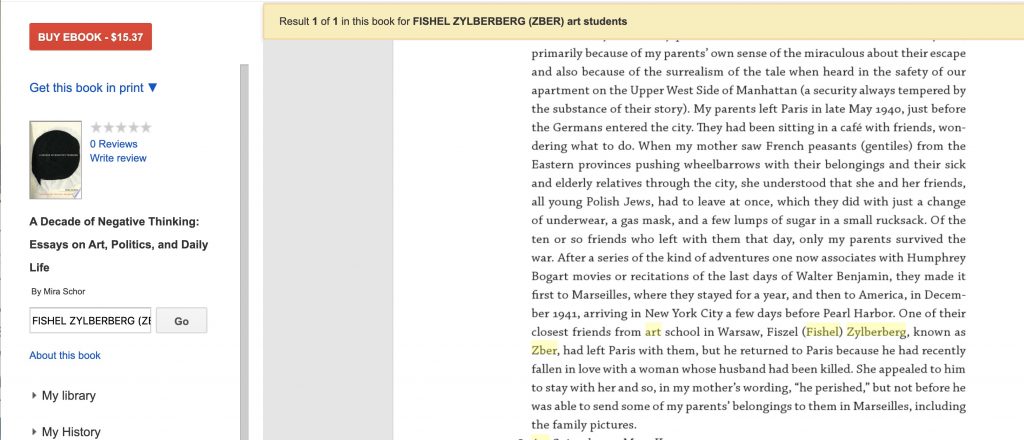

In her book, "A Decade of Negative Thinking: Essays on Art, Politics, and Daily Life" (January 2010), artist and writer Mira Shore, writes about the close friend of her artist parents, Ilya and Rasia Shore, of the Warsaw School of Art (see photo), Fishel (Fiszel) Zylberberg-Zber: “He left Paris with them [her parents] but he returned to Paris, because he had recently fallen in love with a woman whose husband had been killed. She appealed to him to stay with her and so, in my mom’s wording, ‘he perished.”

Stania Bondar – wife and activist in the anti-Nazi underground in Paris

While writing about Fishel zylberberg-Zber, one must pay homage to his wife, Stania Stanislav Bonder. She was born on December 24, 1911 in Warsaw. In 1926 she came to Paris to study law and later, although not a painter, she studied at the Paris Academy of Art.

Stania participated in anti-Nazi activity in Paris and was murdered in Auschwitz in 1944. She was deported under the name "Guta Rosenstein". Before she was arrested, she managed to hide some of her husband's art work.

At Stania's house, the underground, prepared explosives and did other covert operations against the German enemy.

Indeed, once an explosion happened in the house and two wealthy Jews from Poland Ivo Mullen (underground name) and Salk Bot, a gifted musician, perished while preparing explosives. The house was ruined, of course, miraculously, Stania managed to escape Paris.

She hid in the villages and continued to work in the underground movement under the name, Alice Buda. Her job was dangerous: She had to go to the various municipalities and ration offices and replace the food cards of the underground members. She was under constant danger for being snatched by the secret agents who roamed these offices.

After her husband, the artist Zylberberg-Zber was arrested and taken to the camp. She attempted to do everything to save and hide his paintings. According to testimony by Monique Hefner born Formansky on the French witness site (2014 Les Temoins), he remarks about the friendship formed between his father, Isaac Formansky (later, chairman of the Association of Former Nazi Prisoners in France) and Fishel zylberberg-Zber. He reports, “one day, Stania, arrived in our home, with a box of pencil drawings, asking to shelter them. They were portraits of prisoners and old men in hospice. The family later gave them to the Museum of Jewish Art.”

On November 16, 1943, at 12 o'clock midnight, Stania was arrested and taken to the Paris’ police station, where she remained for two weeks. From Paris, she was taken to a prison in Fresnes, where she was jailed for three months.

In Fresnes, Stania was interrogated by Special Brigades and was accused of “communist terrorist activity.” Despite being weak and frail, she endures with utmost courage the torture and German’s beatings; their aides failed to extract any information from her. On January 20, 1944, she was transferred to the Drancy Concentration Camp, north of Paris under the number 1184. The camp served as a transit station for the deportation of the city's Jews.

On February 3, 1944, she was deported in convoy No. 67 of 1214 deportees, men and women bound for Auschwitz. She was deported under the name "Guta Rosenstein." Immediately after their arrival, 985 deportees were burned in the gas chambers. When the Russian army liberated the camp on January 27, 1945 only 26 survivors remained of this convey including 12 women. Stania (Guta Rosenstein) was dead, murdered in the same gas chambers that exterminated her husband, the painter Zber, two years earlier.

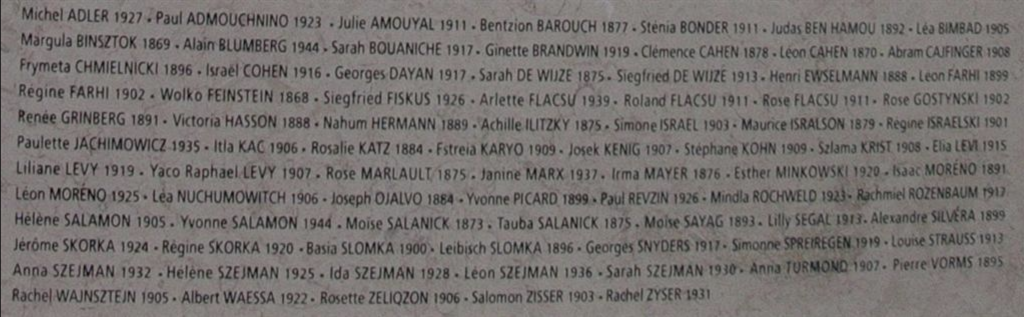

The name of Stania Bonder is engraved on the Memorial to the Holocaust, at the Holocaust Museum in Paris.

Stania Bonder's name is engraved on the Memorial to the Holocaust, at the Holocaust Museum in Paris - Top raw, third from left

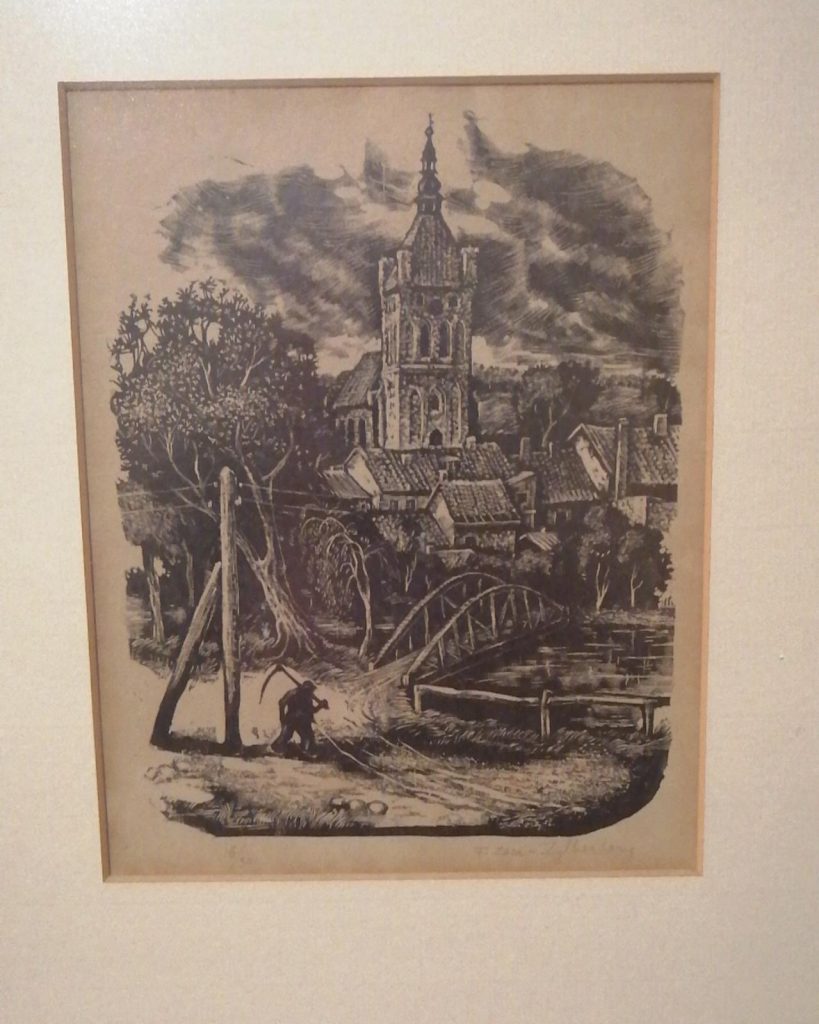

Woodcut, print 16/30 (date is not available). Signed F. Zber - Zylberberg. From the collection of Amos Avivi. Dan Fliderblum-Avivi's son