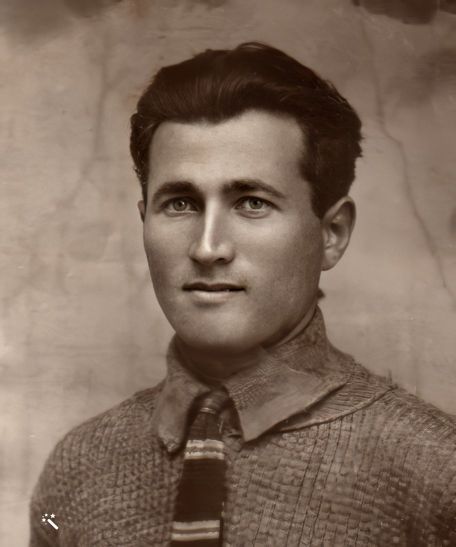

Aaron Pomerantz

1901-1930

Aaron Pomerantz (Moshe “Pommy” Hadar’s father) was born in 1901 in the city of Aleksandraw, Lodz, in central Poland. His parents were Moshe Nathan Pomerantz and Sarah Pomerantz nee Nordenberg. In 1904 his brother Isaac was born. A sister named Friedel was born (date unknown). She died during a surgery at the age of 12. In 1912, his sister, Masha was born. Two months before Masha's birth, the father, Moshe Nathan, died of typhoid. Sometimes after the father's death, the family relocated to Rypin.

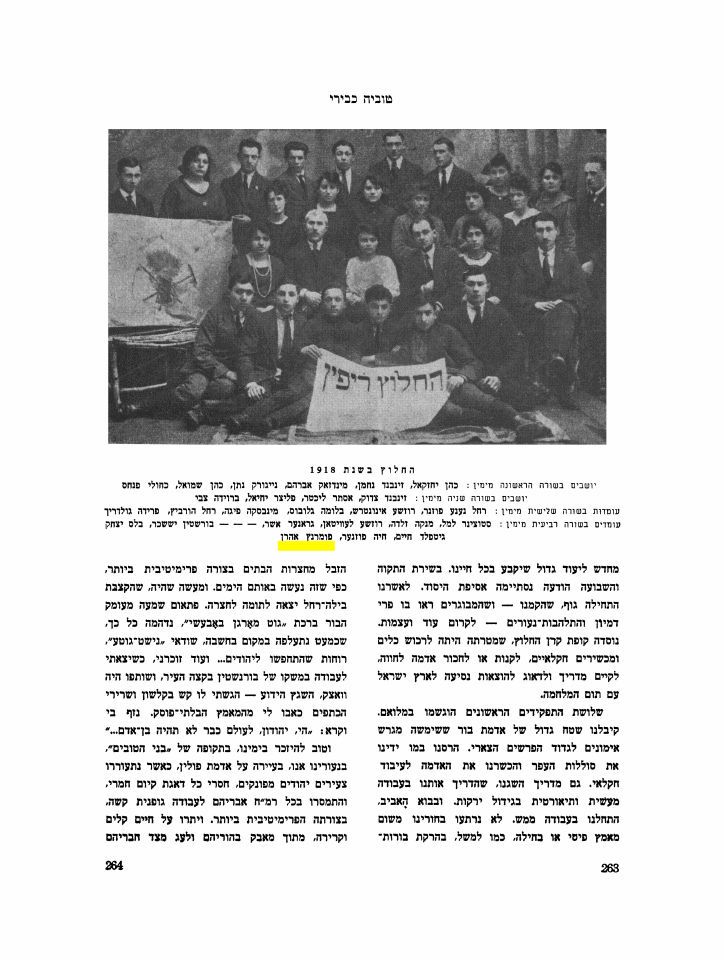

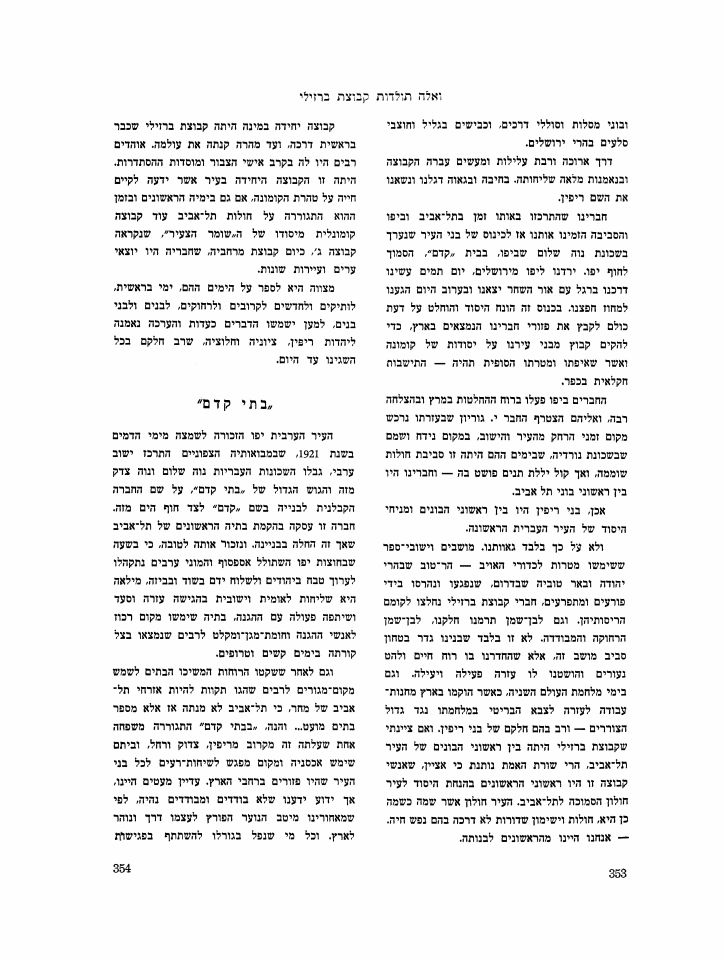

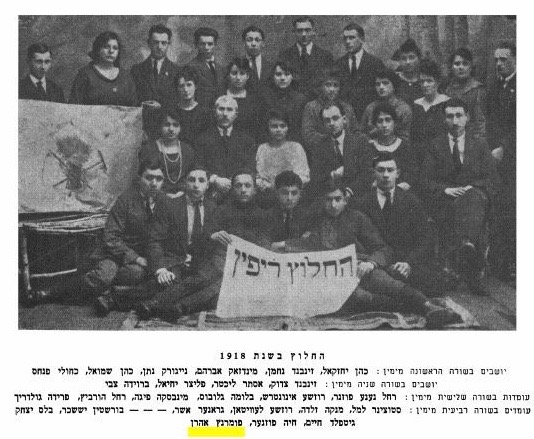

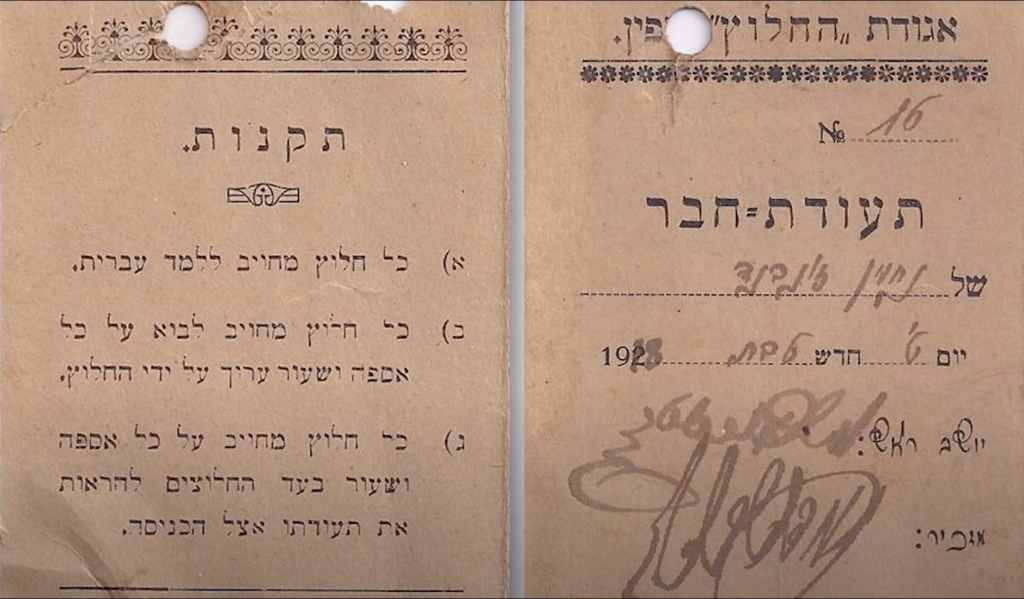

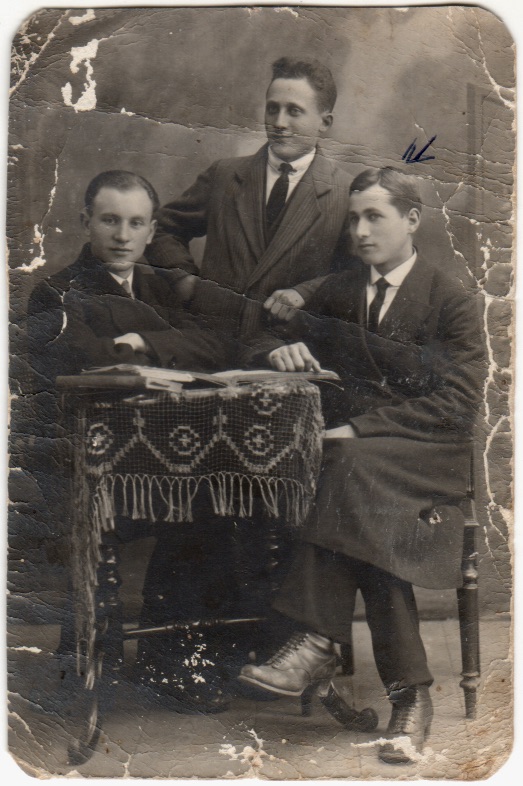

The HeChalutz in Rypin, 1918

Aaron Pomerantz, Last row, standing first on the left

Certificate of membership and rules – the "HeChalutz" Group of Nachman Zonband from 1918, brother of Avraham Shabtai (Zonband), husband of Masha (Aaron's sister). The certificate was obtained courtesy of the Shabtai family.

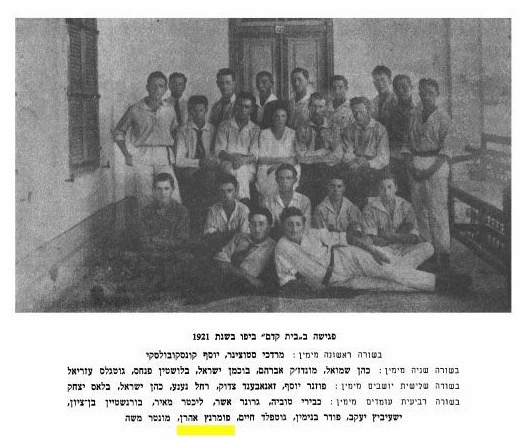

Aaron Pomerantz with the HeChalutz – Rypin group in memory of the first group to Eretz Israel, February 9, 1921. The photo from the album of the Shabtai family, Rachel and Zadok – brother of Avraham Shabtai, husband of Masha, sister of Aaron Pomerantz

On a rainy winter day, in 1917, in the midst of the First World War, a group of young men and women from the city of Rypin gathered at the community center, paving the groundwork for HeChalutz, The Pioneer. Then and there they decided on the shape of the flag – seven stars against a white light azure, a hammer and a scythe combined with a wheat stamen. Aaron Pomerantz was one of the founders of HeChalutz. Their goal was to train young people for future agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel. Their first step was to raise the financial capital needed to lease a farmland, purchase farm tools and equipment, hire an agronomist, who would guide them on practical and theoretical agriculture tasks; and raise further funds to pay for travel expenses to Israel at the end of the war.

In February 1921, Aaron Pomerantz, immigrated to Israel, with the first group of HeChalutzim (pioneers) from Rypin, Poland.

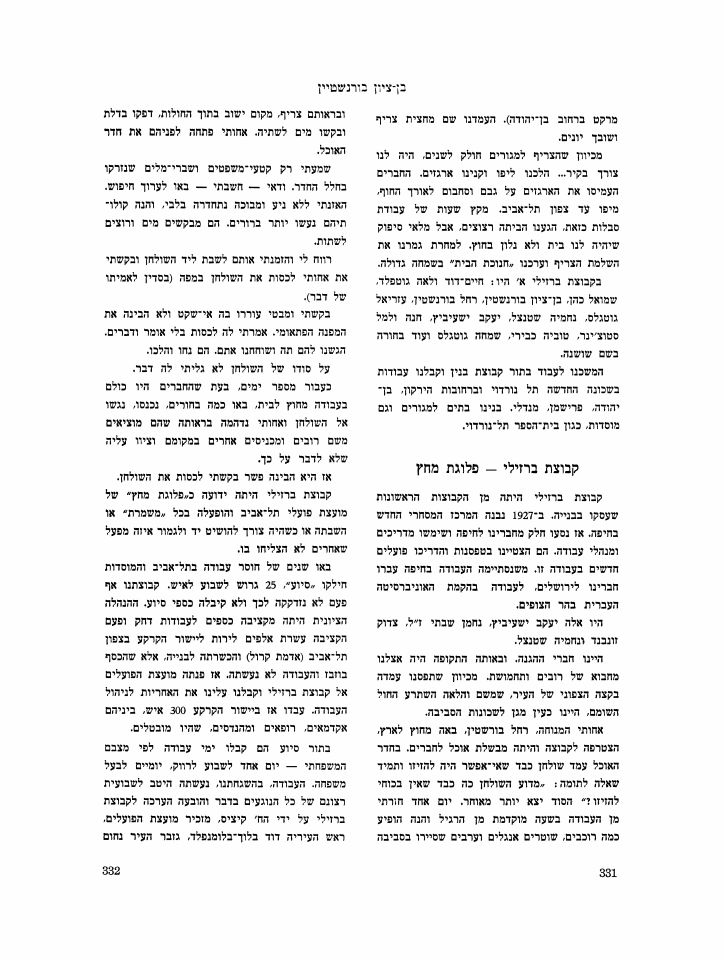

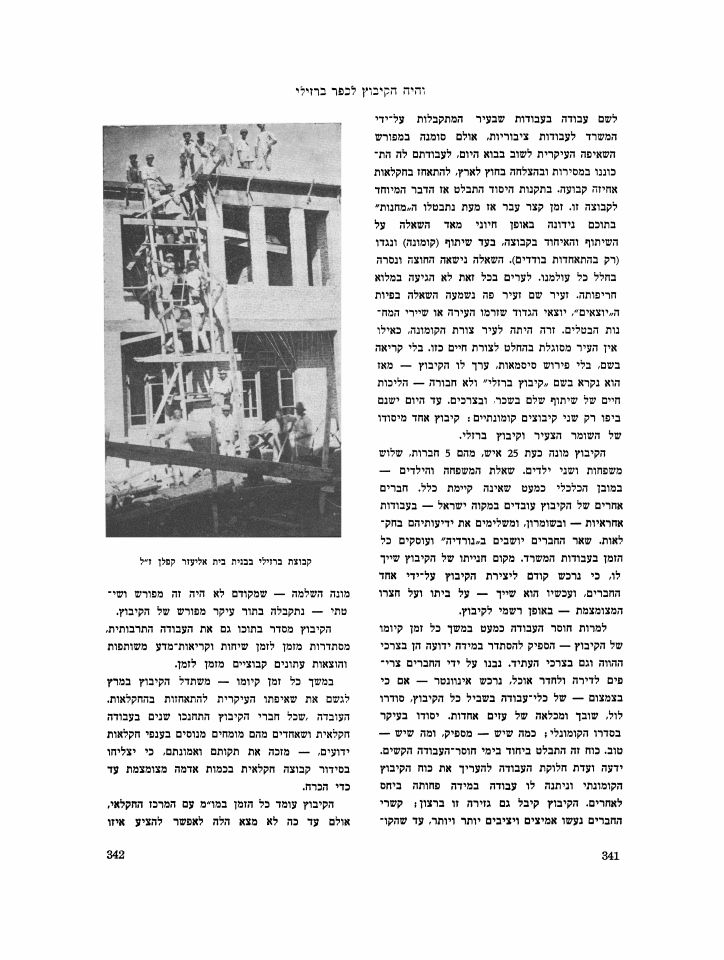

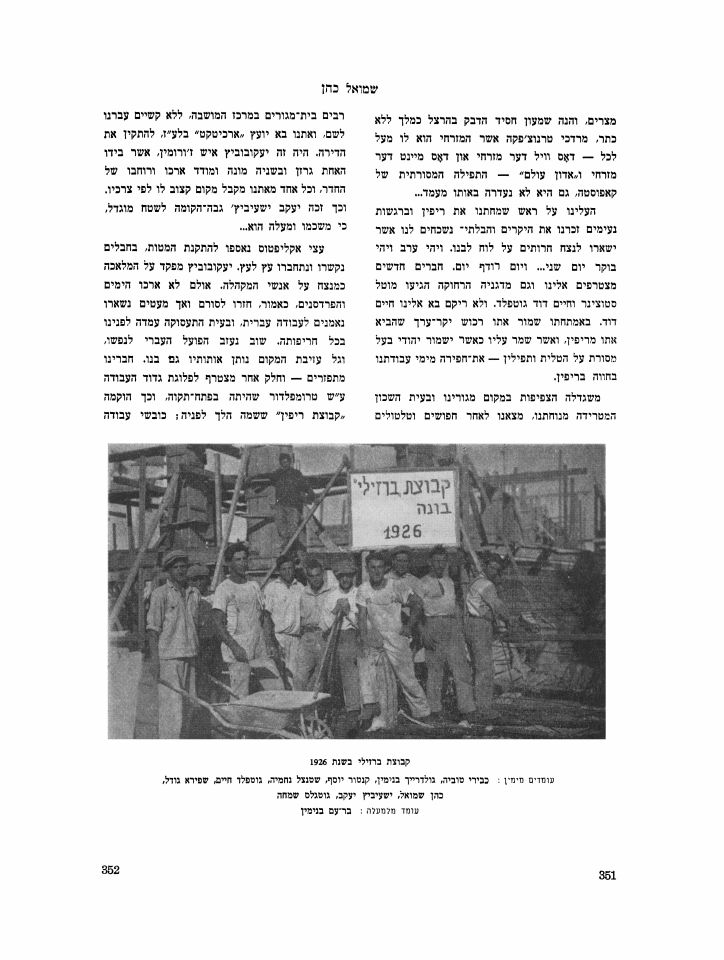

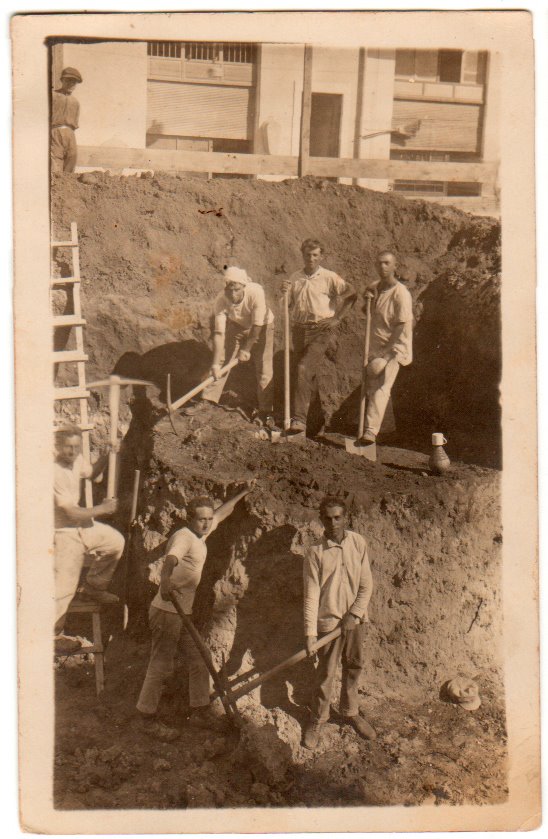

In late 1921, Aaron, with few friends from Rypin, founded the Rypin Group, which later became a Barzilai group (named after their friend, the group's spokesman and secretary of the Tel Aviv Workers' Council, Ze'ev Barzilai, who drowned in the Yarkon River). Their reputation preceded them as hardworking, miners, road pavers, admirable construction workers and well-trained crew of excellent specialists. They penetrated the building industry and carried out great contracts to the satisfaction of the Ministry of Public Works and the Building.

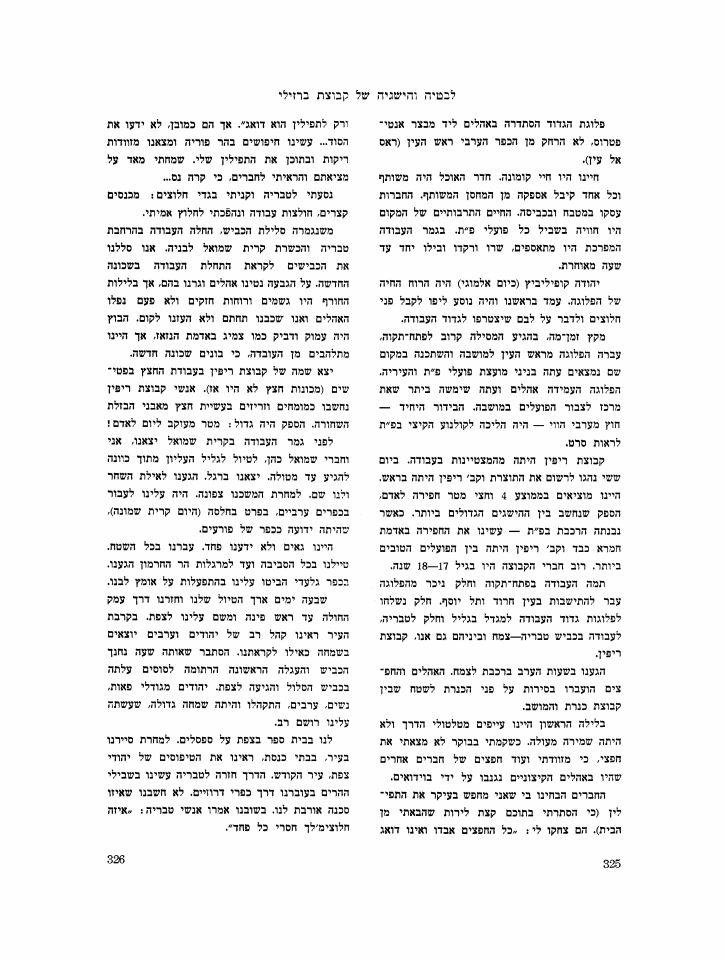

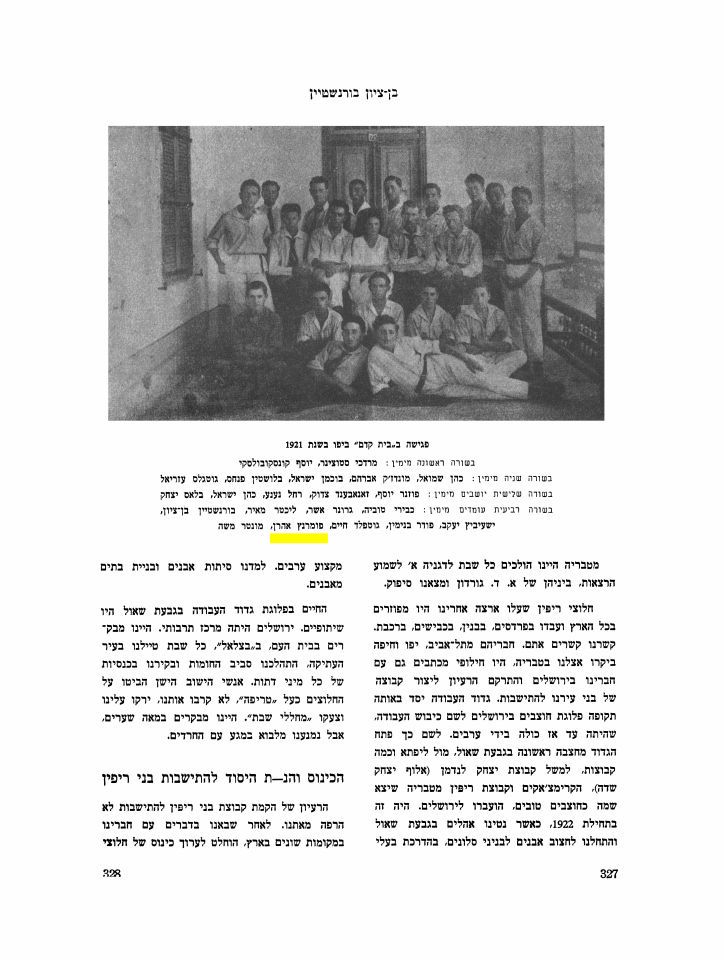

Meeting in Beit Kedem, Jaffa, 1921

Aaron Pomerantz , fourth row, second from left

Office of Public Works - "Bureau of Employment" at the time

In the same year, 1921, the General Organization of Workers in Israel “The Histadrut” was established to look out for the interests of Jewish workers. They formed the Office of Construction and Public Works under the name of Batz (בע"ץ), an acronym of Binyan veAvodot Tziburiot (בניין ועבודות ציבוריות, lit. Construction and Public Works) as a cooperative society, in the spirit of the socialist working groups – the ideology of fulfilling Zionism through the occupation of labor and the establishment of a layer of Jewish workers in the Land of Israel to strengthen the control of the Jewish people in its country. They engaged in organizing and contracting groups of people for public works and also acted as an employment bureau.

The Construction and Public Works engaged initially in paving roads and then it turned to construction work in cities and farms, drying wetlands and establishing irrigation plants. It also worked on the design and construction of government buildings, hospitals, schools, ports, bridges, police stations and post offices in the service of the British Mandate administration in Palestine. In addition to the ministry's activity in building the country and securing employment for Jewish workers, it contributed to the professional training of immigrants and their adaptation to manual labor. Many historians attribute the activities of the Construction and Public Works to the growth and socio-economic development of the Israeli society in its early days. The emphasis of this program was to provide new immigrant integration and financial security – creating a new whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Throughout its operation the Office of Construction and Public Works was under water, suffering from enduring deficits. Some of the deficits stemmed from the fact that the workers, after being trained and becoming professionals, moved to work as self-employed workers at higher wages, leaving unskilled workers in the service of Construction and Public Works. In 1924 the Histadrut decided to extend its responsibilities of the Construction and Public Works by founding a company named “Solel Boneh,” based on the organization but managed as a business corporation. Aaron started working for Solel Boneh as a construction supervisor.

Aaron in the top row in the middle, hand on the waist

Aaron in the middle, hand on the waist

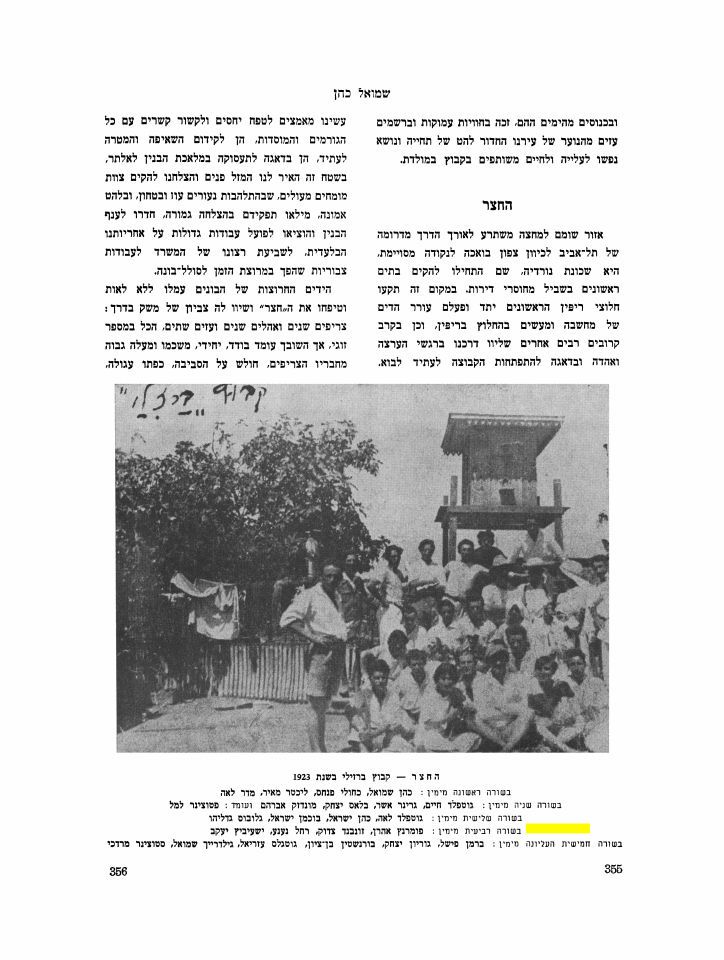

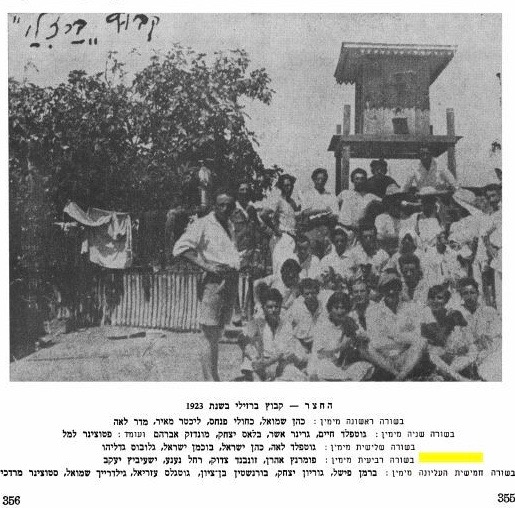

The First Commune in Tel Aviv

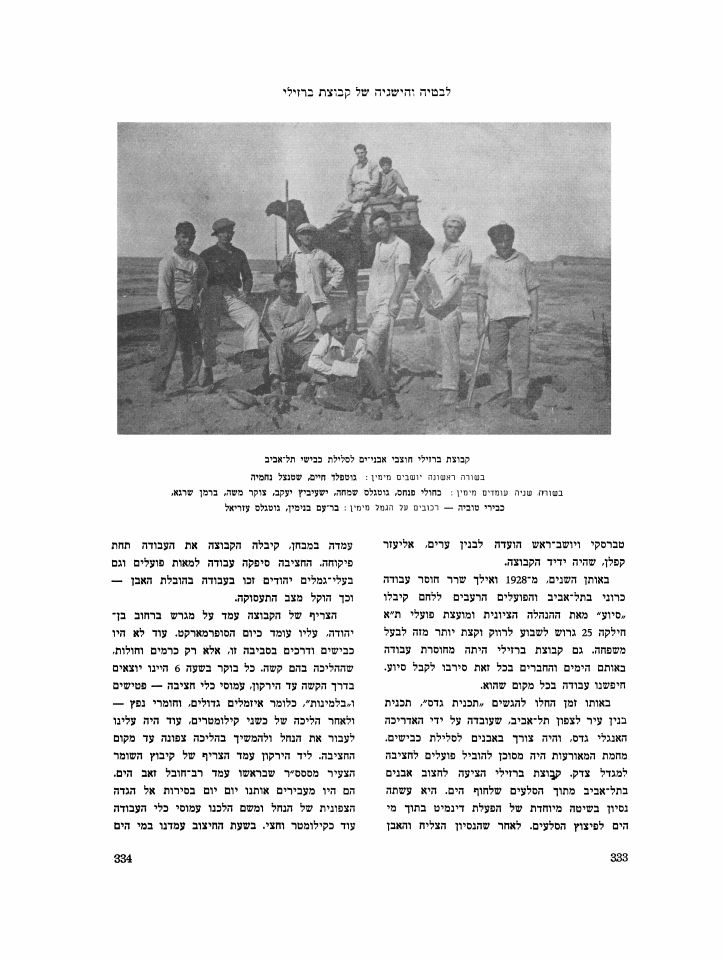

In the heart of Tel Aviv in 1922, between vineyards and sands, the Rypin pioneers and the Barzilai group set up a home and inaugurated the first commune in Tel Aviv. With the help of the friend Yitzhak Gurion, a remote location was purchased in the Nordia neighborhood (today's Dizengoff Center), which in those days was a desolate sand dune.

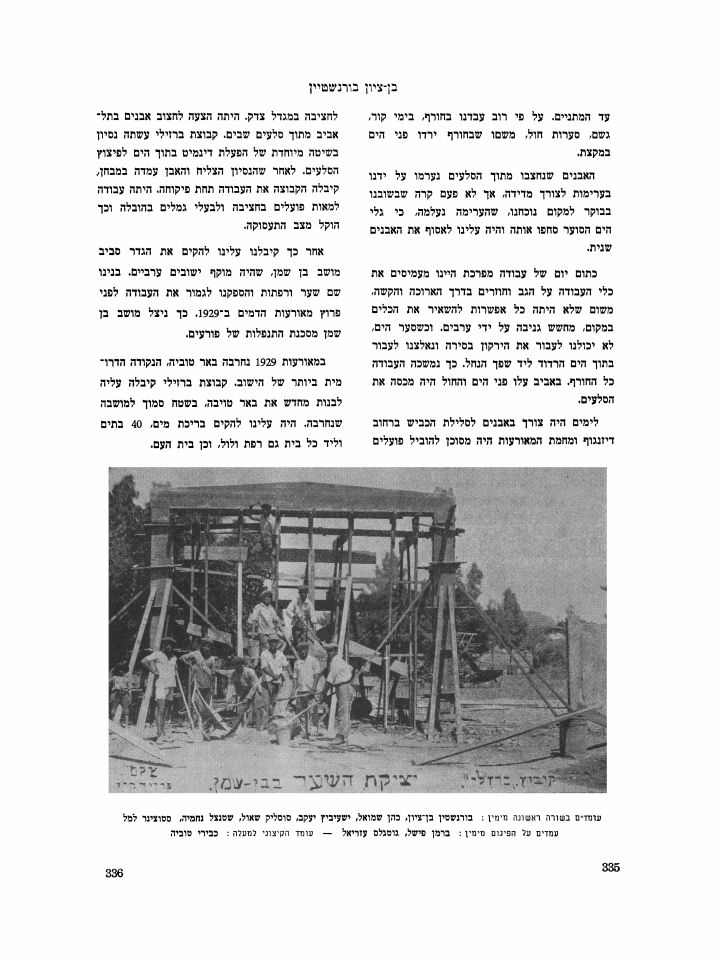

Ben Zion Bornstein wrote, "We set up tents and a hut as a living space with a dining room. We were about 25 guys and one woman. The group was formed for the purpose of an agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel, but because the Israeli Agricultural Center of the Workers' Union lack funds, we worked as construction workers and formed an urban Kibbutz.” (Rypin Yizkor Book, 1964, P. 329)

The yard at Kibbutz Barzilai, Nordia, Tel Aviv, 1923

Aaron, fourth row, first on the right

Aaron Pomerantz, third in the middle points to the plans

Aaron Pomerantz, bottom row, second from right, with hand on the waist

According to Samuel Cohen’s account regarding the History of the Barzilai Group in Rypin Yizkor Book (Pages 349-359), he writes, "Our friends were among the first builders of Tel Aviv. And this is not our only pride. We constructed farm land in boarder settlements that served as targets for enemy bullets – Har Tuv in the Judean mountains and Be’er Tuvia in the south, who were harmed and destroyed by rioters. Members of the Barzilai group, resurrected the ruins. And we also lend a helping hand to moshav Ben Shemen… And during World War II, when work camps were erected in the country to help the British army…The group members were the first to lay a foundation to the city of Holon…”

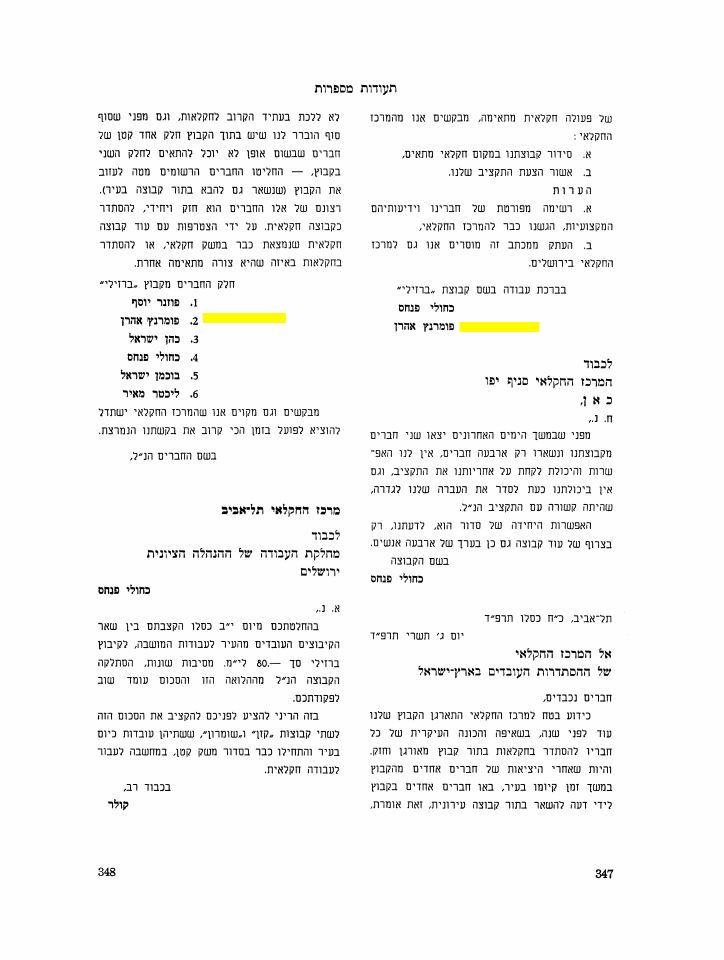

The urban kibbutz in Nordia, continued its existence until 1924. "In the meantime, a few friends had dropped out, they found mates and left the group to started their own families. After the departure, the kibbutz splitted into two: one part rooted in construction and the other half aspiring to form a land settlement. 'See a letter from October 1923 sent to the Israeli Agricultural Center of the Workers' Union, which is signed by Aaron Pomerantz.

According to the letter, the members signed below want to split from the members who wish to remain as an urban group. They decided to leave the urban kibbutz, "The will of these members is strong and unique, to strive and build an agricultural group."

At this point, no more documents or concrete evidence could be found to determine what happened next. History and family facts suggest that Aaron Pomerantz stayed in Tel Aviv, met Bracha Zibenberg and got married on or about 1925. Conversations with relatives, point to Aaron’s innate grasp of building construction, engineering, architecture, and a keen eye to real estate. Aaron began to climb the professional ladder, becoming a foreman in the Public Works Office and then a building supervisor.

In August 1926, his first and only son, Moshe (Pommy) Pomerantz (Hadar) was born.

In 1927, the Barzilai Group served as instructors and managers for construction projects throughout the country. They were known as the “infiltrate squadron” of the Tel Aviv Worker’s Council. They were activated every shift or downtime or to complete projects that others were unsuccessful executing. They were active members of the Hagannah and hid guns and ammunition in a slick (cache) inside the dining table in their Nordia Hut.

In 1928, the Barzilai Group helped fulfill the Geddes Plan, the first blueprint for the city of Tel Aviv (the center of Tel Aviv and the Old North), which was designed by the English architect Patrick Geddes. Stones for pavements of roads and sidewalks were needed. Because of the hostile incidents, it was dangerous to lead workers to the quarry at Migdal Tzedek. The Barzilai group proposed to excavate stones in Tel Aviv from the rocks offshore. The group tried a new and a special method by using dynamite in the seawater for rock blasting. After the experience was successful and the stone was put to the test, the group got the job contract. The quarrying provided work for hundreds of workers.

In 1929, the Histadrut or the General Organization of Workers in Israel aimed to free the urban worker from the burden of high rent, improving living conditions and creating labor-workers culture. Aaron was appointed to supervising manager (until he had fallen ill) at the construction of the first workers neighborhood in Tel Aviv, with thirty-five single-story with an auxiliary farm of about half an acre adjacent to each home. The neighborhood was designed by engineer David Tuvia on a 30-acre site in place of an almond vineyard, owned by the Jewish National Fund and located between Keren Kayemeth L’Israel Avenue and La’sal Street. The price of each house was about 350 lira Eretz-Israelit and most of the landowners paid it in installments. Pommy's father, Aaron Pomerantz, and his wife Bracha bought a parcel at 3 Keren Kayemeth L’Israel Avenue.

In 1930, Aaron contracted tuberculosis and was sent to Hadassah Hospital in Safed, where three years earlier, a TB department was established due to the clean and crisp air quality up in the northern mountains. Gradually, the hospital moved to treat only lung and tuberculosis patients and only one ward remind open, serving as a maternity ward.

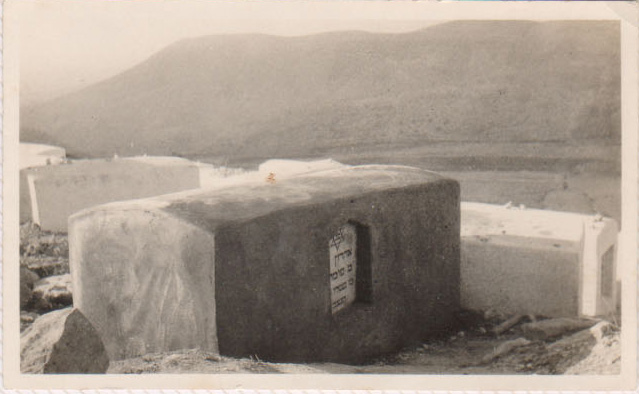

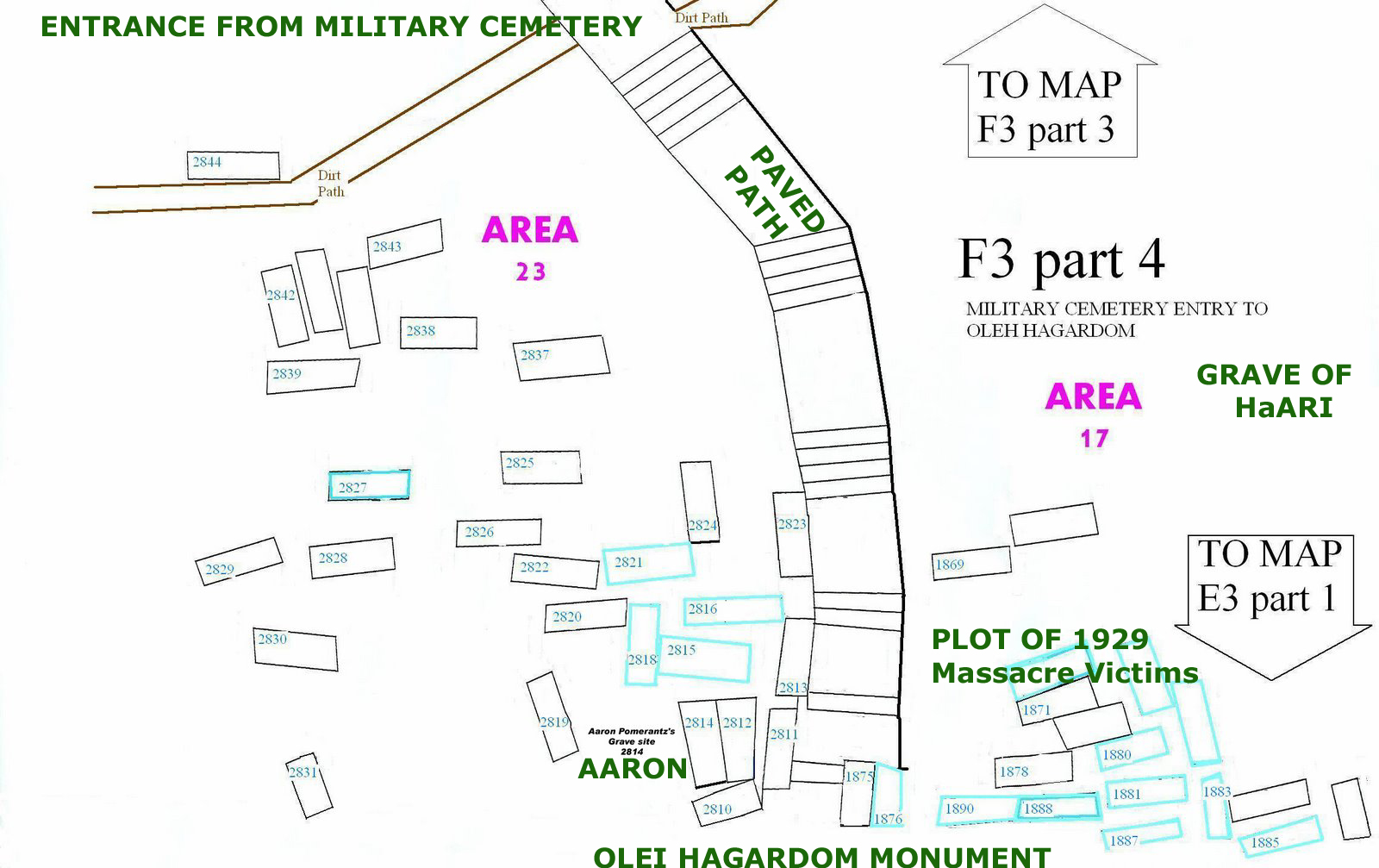

Aaron Pomerantz succumbed to TB on the second candle of Hanukkah, 1930, at the age of 29. He survived by his wife, Bracha and his four-year-old son, Moshe "Pommy." Over eighty years of exploration, disappointments and anticipation have taken Pommy to locate Aaron's grave. In 2009 the tomb was found. Aaron is buried in the old cemetery in Safed. His grave located on the other side of the path where the slaughtered victims of the August 29, 1929 Safed riots were buried; and few yards above the memorial to Olei Hagardom (Hebrew: lit. "those who ascended to the gallows"). At a parallel pathway from Aaron’s grave is the grave of Isaac Luria (The Ari).

FINDING AARON'S GRAVESITE, 80 YEARS LATER

THE MIRACLE OF PICTURES The Following two images led me to discover, my paternal grandfather, Aaron Pomerantz’s grave. In 2009, after a year of remodeling my parents’ home, a leak from a defected water filter in a new refrigerator, flooded the whole downstairs. The incident prompted me to digitalize all my parents photo albums and mementos. During the process I discovered the enclosed images.

BACKGROUND

Aaron Pomerantz died from tuberculosis (TB), at age 29, ninety years ago, on the second candle of Hanukkah. Aaron was a close friend of David Ben-Gurion and a supervising manager at the first paving and building company in Israel (Solel Boneh). In late 1929 Aaron was appointed to supervise the construction of the first workers neighborhood in Tel Aviv, and Ben-Gurion’s home. In mid 1930 Aaron contracted TB and was sent to Hadassah Hospital in Tzfat (Safed), where three years earlier, a TB department was established due to the clean and crisp air quality up in the northern mountains. Nevertheless, Aaron succumbed to the infectious disease and was buried in the old cemetery in Tzfat (Safed). The cemetery covers 120 dunums (29.5 acres) and over 4000 tombstones, which spreads out over a steeply sloping hill facing Mount Meron. While the cemetery is best known for the great scholars from the Middle Ages who are buried there, it is also known as the burial grounds for Jews who lived in the area thousands of years ago.

At the time of Aaron’s demise my father was 4 years old. As my father approached adulthood, he longed to visit his father’s gravesite but to no avail. Over the years and during Israel War of Independence in 1948, many of the tombstones at the ancient cemetery in Tzfat (Safed) were desecrated and vandalized by Arabs. The registration records and gravesite maps were either destroyed in fire or vanished circa 1939. Furthermore, landslides as well as the slow and steady erosion of the slopes, took down many of the tombstones, adding further confusion.

For years my dad searched for the grave site. As time passed, my father became more apprehensive about searching for Aaron’s gravesite; dreading renewed disappointments. Nevertheless, he proactively looked for the gravesite, each time dealing with another blow of frustration and another loss. With the passage of time, my father came to the conclusion that the father he barely knew, lived on the slopes below the Old City of Tzfat (Safed), breathing clean mountain air and being part of the great mystique of the past.

Every year, on the second night of Hanukkah, my father would light a yahrzeit candle, hoping for a miracle – that one day he would find his father’s gravesite. In my late teens, I was at Tzfat (Safed) for a weeklong artist retreat; I attempted to locate the gravesite and the tombstone but left empty handed. Over the years, my brother and I made additional efforts to travel to Tzfat (Safed) in attempts to locate the gravesite but gained nothing.

THE MIRACLE PICTURES

When I started digitizing our family’s photos and mementos, I came across a picture from late 1930 or early 1931 of my grandmother (with her brother-in-law, Itzhak Pomerantz) seating on the slope below the Old City of Tzfat (Safed). She is holding a plaque bearing the name of Aaron Pomerantz and his date of demise. In another picture, you can see the actual tombstone.

The above discoveries charged me with a renewed hope. For the first time, I had Aaron’s correct Hebrew date of demise; and I also held a noticeable location. In addition, the tombstone was not a vertical tombstone. It was a freestanding stone coffin, constructed as a monument. This plain sarcophagus like grave had an indentation on the front panel bearing a plaque with Aaron’s information.

I didn’t want to inform my father or raise his hope, yet, again. I started meticulously researching various sites, until I came across the name of Laurie Rappeport, Coordinator of the Livnot U'Lehibanot (in Hebrew – To Build and To Re-Built), who also runs Safed Tourist Information Center. I e-mailed her all my information and the following day she replied with the name of Haim Sidor.

Tzfat’s (Safed) second resource for genealogy researchers is a well-known tour guide, Haim Sidor, who has embarked on a remarkable project of mapping the Tzfat cemetery listing, photographing and mapping the graves. With little support or funding, Haim has, for many years, been quietly visiting the Old Tzfat cemetery several times each month, walking

through the weeds which cover the tombstones to try to decipher the names, birthdates, parents' names, and another information which can be found on these tombstones.

I immediately e-mailed Haim the name but not the pictures. Within 15 hours, he replied:

“I have been working on mapping, registering and photographing the Old Cemetery for many years. My work is only partially complete but so far I have covered about 1/3 of the legible graves. I am happy to inform you that the grave you are searching for is among those that have been mapped and photographed (the dates and other information correspond to the information you sent) and I should be able to find it again reasonably easily. Attached you will find a picture I took some years ago.”

I clicked on the icon and opened the picture. As soon as I saw the weathered plaque, my heart leaped and tears started tumbling onto the keyboard, cascading down and washing away years of mystery.

I forwarded the e-mail to my father and called to inform him of the Miracle in Tzfat (Safed). There are no words to describe my father’s happiness and relief. He was over an obstacle, which has been ever so present for almost 80 years.

FATHER AND SON REUNITE

We immediately made plans to travel to Israel and to Tzfat (Safed). On October 21, 2009, my father, mother and I arrived at the Old Cemetery in Safed. Next door to Rabbi Isaac Luria (HaAri) burial site, at an altitude of 2,953 feet, we entered the Military Cemetery and climbed down the steep hill and long stairs. As we descended, we passed by tombstones with inscriptions that revealed the presence of sages and mystics; further down we saw the burial site of the victims of the 1929 Arab pogrom (massacre) in Safed. Few feet away, at the end of the path, we spotted the monument to the Jewish underground fighters who were hung by the British (Oleh HaGardom – "those who ascended to the gallows"). To the right of the path, next to a large cypress tree, we located Aaron’s tombstone.

At last, my father, at age 84, had achieved a lifelong dream, paying his long-awaited respect to his father, Aaron. The feelings overflowed, unlike any I had ever experienced before. My father discovered the truth, yet until we have felt its force, it was not ours. Like red lanterns, the site light up our hearts as love, mystique and serenity reunited Father and Son.

Aaron Grave, Old Cemetery, Safad 1931

Pommy, for the first time ever, at Aaron's grave, October, 2009

Grave # 2814

The historian and the tour guide, Haim Sidor, built a comprehensive database of the graves at the Old Cemetery in Tzfat. Aaron's grave was one of the graves, he mapped

At the conclusion of sheloshim (the formal 30 days mourning period), Bracha and her brother-in-law, Yitzhak Pomerantz, on the slops of the Old Cemetery, holding Aaron's grave marker, January 1931

Aaron, on the left holding Pommy. Next to him his Bracha. In the middle is the matriarch, Sara Pomerantz. To the left his brother, Yitzhak and sister Masha, 1928, Tel Aviv

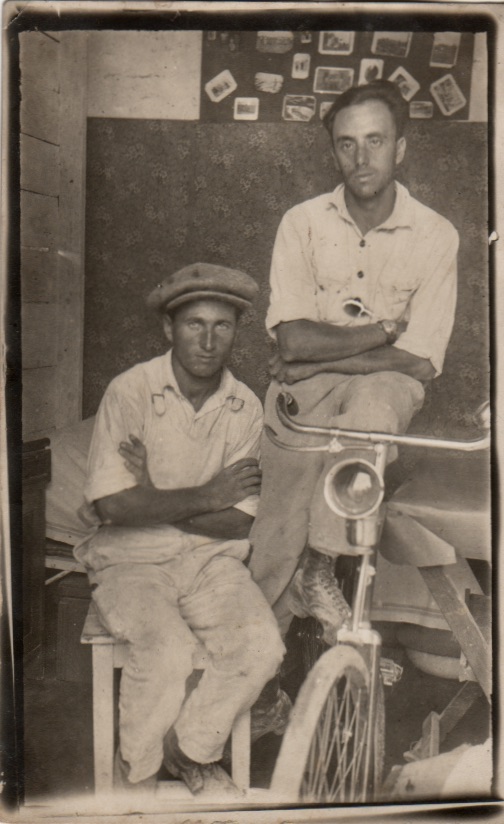

Aaron on the right, with an identified guys

Aaron on the right, with his brother Yitzhak

Aaron and baby Moshe at the Tel Aviv beach, 1928

Aaron and Bracha

Aaron, on the left

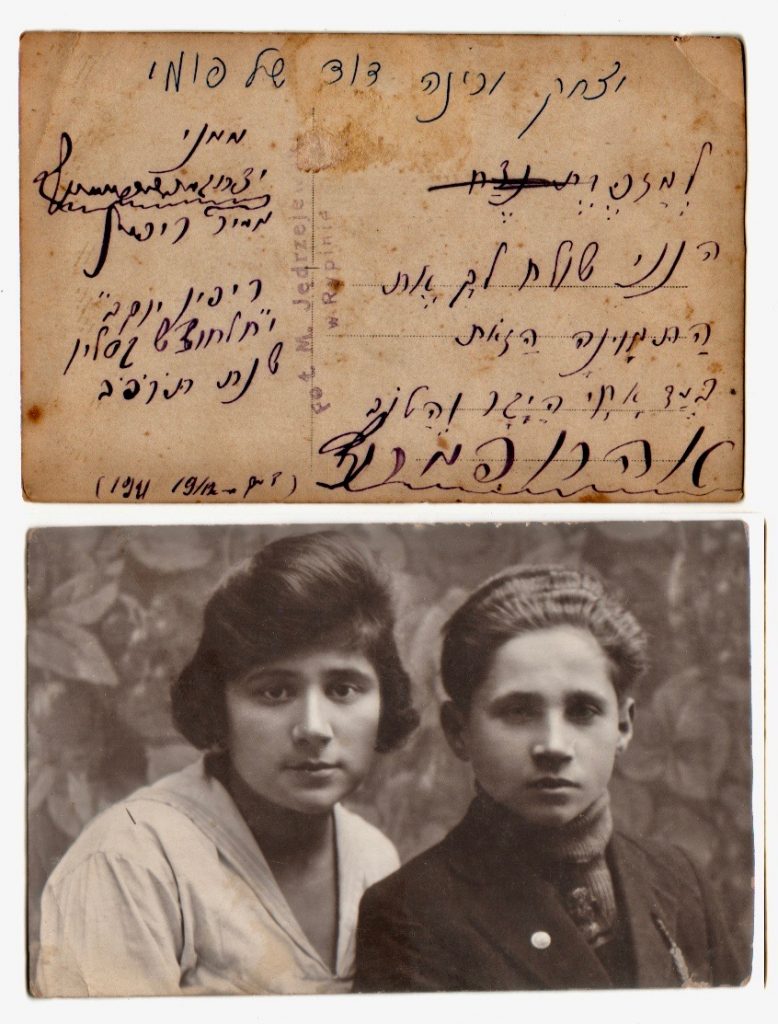

Postcard from Yitzhak, in Rypin to his brother in Israel, dated 19 December 1921. According to the inscription, the girl is Rina, was later became, Yitzhak's wife

Aaron (top row first on the right) with a group of unidentified individuals

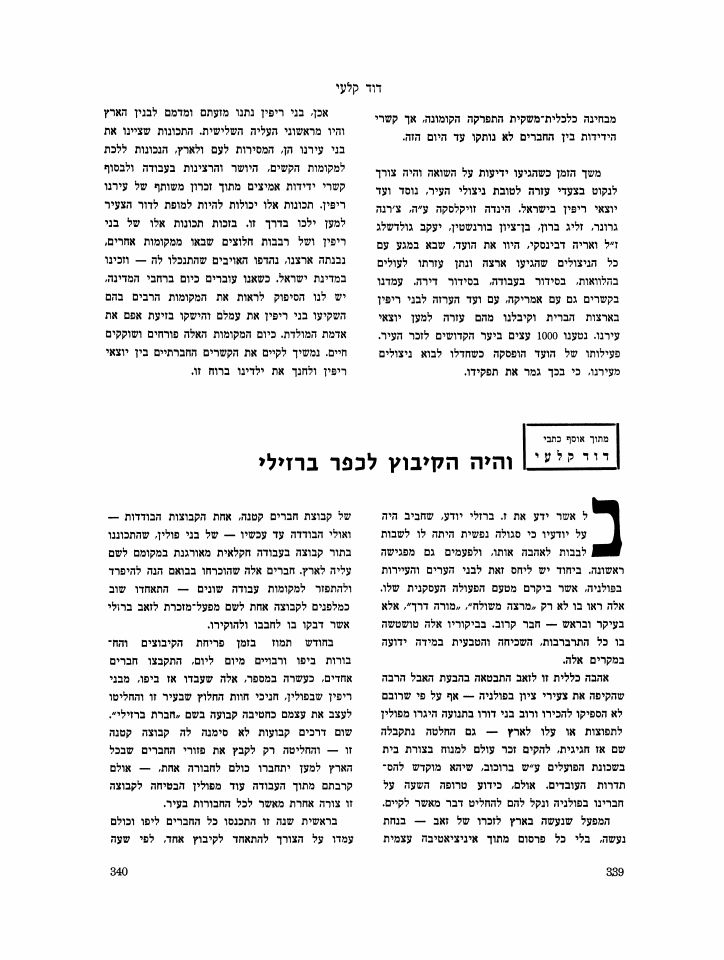

Rypin and the Barzilai Group, Rypin Yizkor Book, 1964