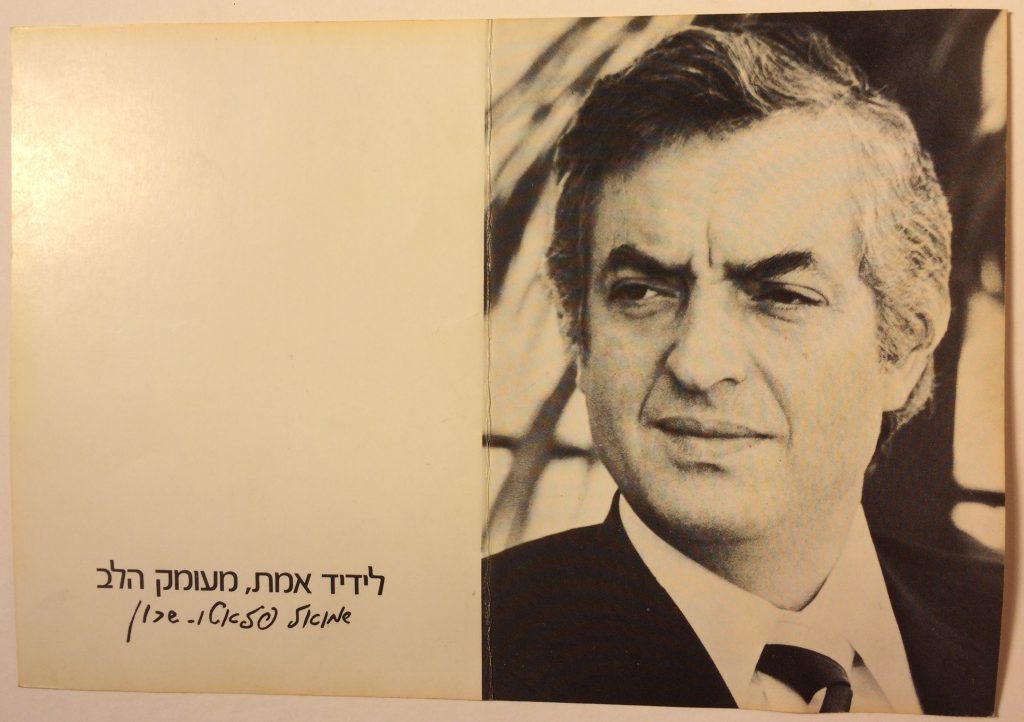

"A Lone Man to the Knesset"

Pommy spear headed many broad-spectrum and political campaigns in Israel. He was known as the man who mastered the art of persuasion. Enclosed herein is one of the more colorful and controversial election campaigns to the Knesset

How it All Started

On a frigid February night in 1977, the moon cloaked behind ominous clouds, Tel Aviv stirred with the eerie brilliance of thunderstorms and flashes of lightning. The Hadar household shivered beneath this celestial spectacle when a ring echoed through the frosty air, piercing the stillness of the night. The voice on the other end belonged to Meir S., an emissary of destiny, Pommy's comrade from the years of youth.

"Pommy," he uttered urgently, "you must save a Jew." A mandate that hung in the air, a whisper that set events in motion. "In half an hour, a driver will pick you up."

At the appointed hour, the chauffeur materialized, and Pommy was whisked away to Savyon, a Tel Aviv suburb. There, in the cold night, he found himself face to face with Samuel Flatto-Sharon, known to intimates as Sammy. A meeting destined, a conversation unfolding in the rhythmic cadence of English, as Sammy, then, was more familiar with the tongue of Shakespeare than the ancient whispers of Hebrew.

Born in Lodz, Poland, to a lineage that bore the Jewish stamp, Sammy's family had fled the clutches of Nazi occupation to the haven of France. In Paris, a city of whispered affluence and clandestine dealings, Sammy began his dance with commerce, peddling cigarettes to students and soldiers. A journey marked by triumphs and echoes of the title "King of the Paris Recycling Industry," he spun a web of enterprises that spanned continents, entwining France, Africa, the United States, South America, and eventually Israel.

In 1975, the journey led Sammy back to the land of his ancestors, to Israel.

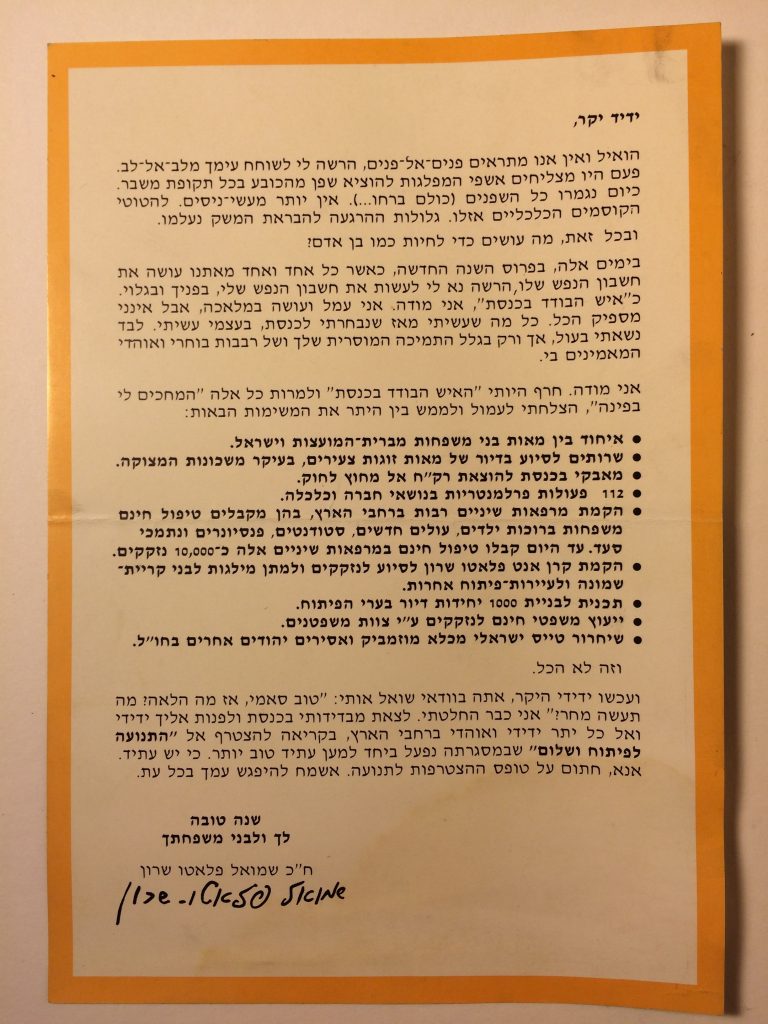

The rendezvous in Savyon unveiled Sammy's plea: a plea to navigate the corridors of power, to secure a seat in the Knesset, the hallowed chambers of Israeli governance. For Sammy believed in the alchemy of political immunity, a talisman against the looming specter of extradition to France. A judiciary system, tainted by the brush of anti-Semitism, had unfurled an international arrest warrant, accusing Sammy of economic malfeasance and tax evasion.

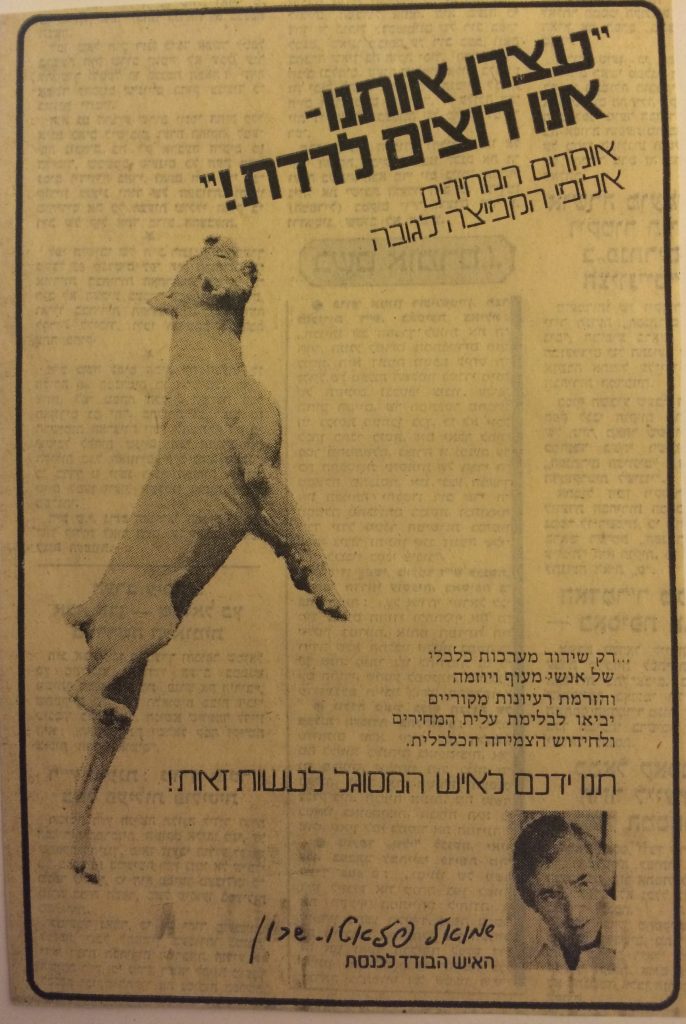

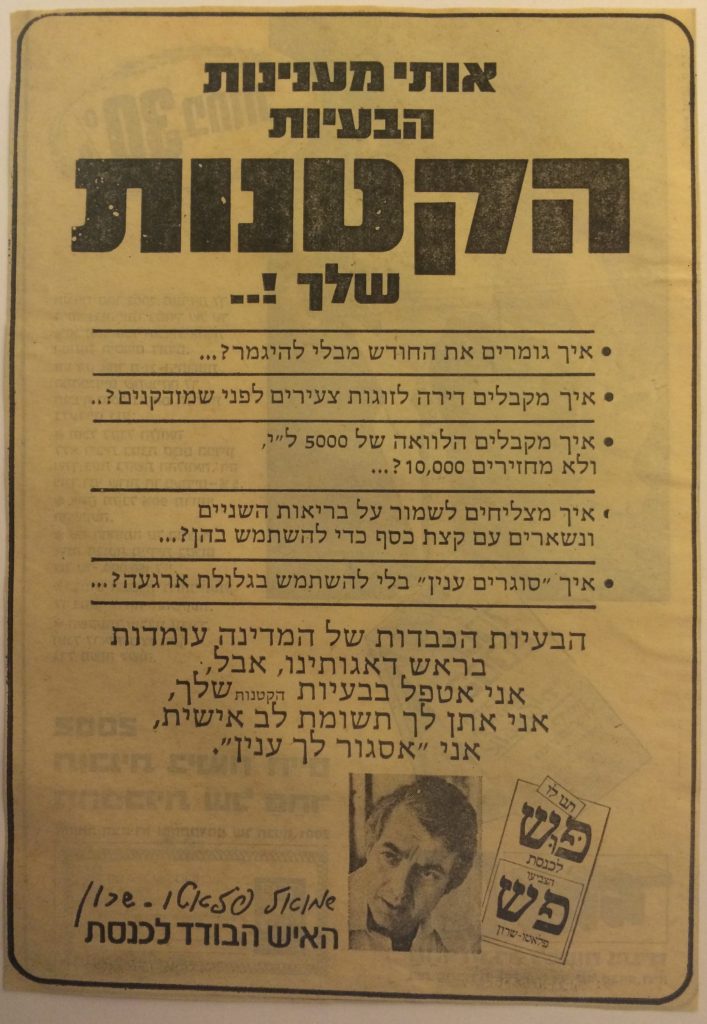

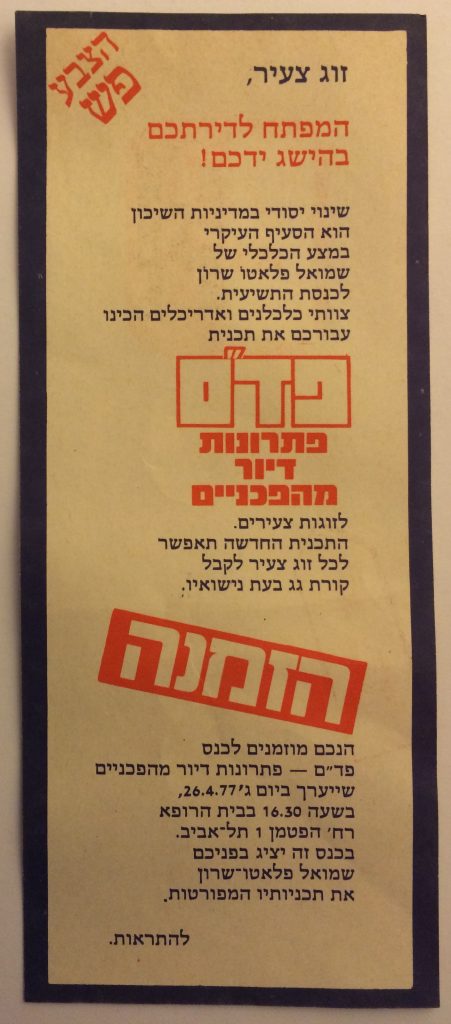

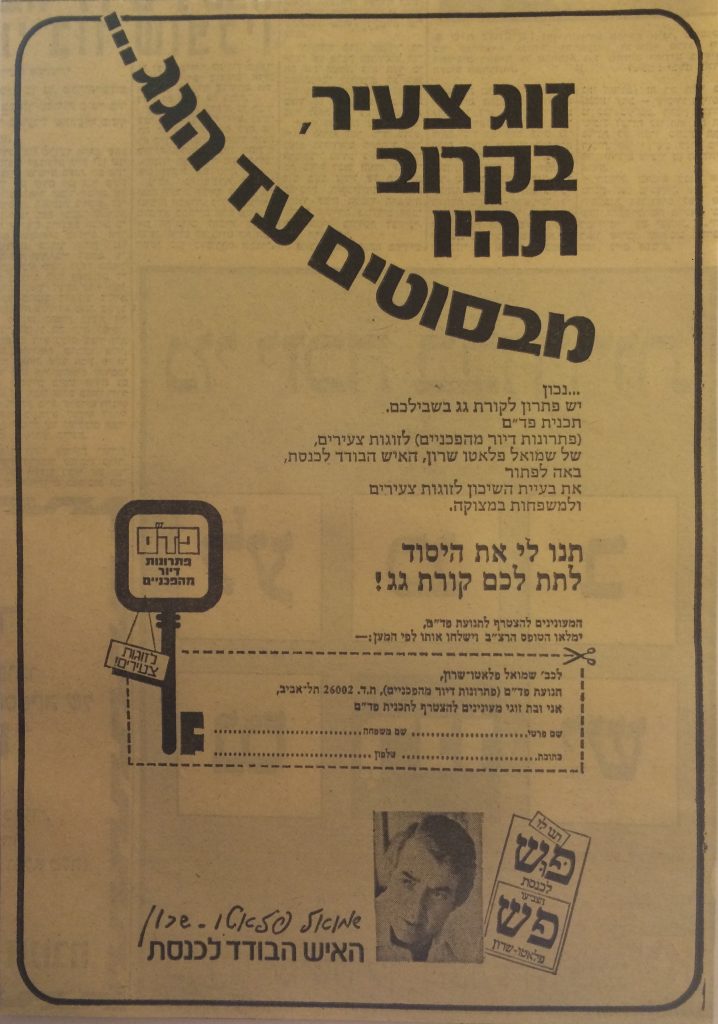

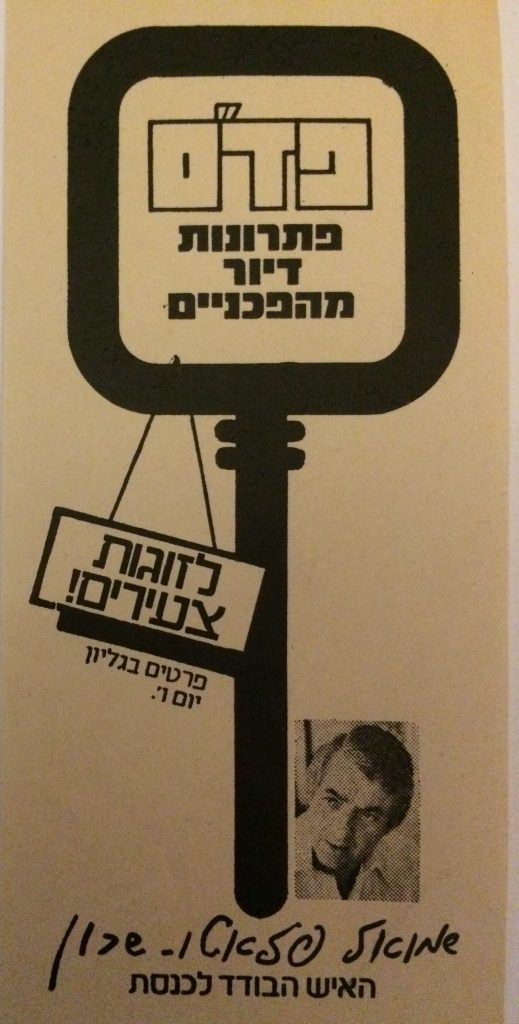

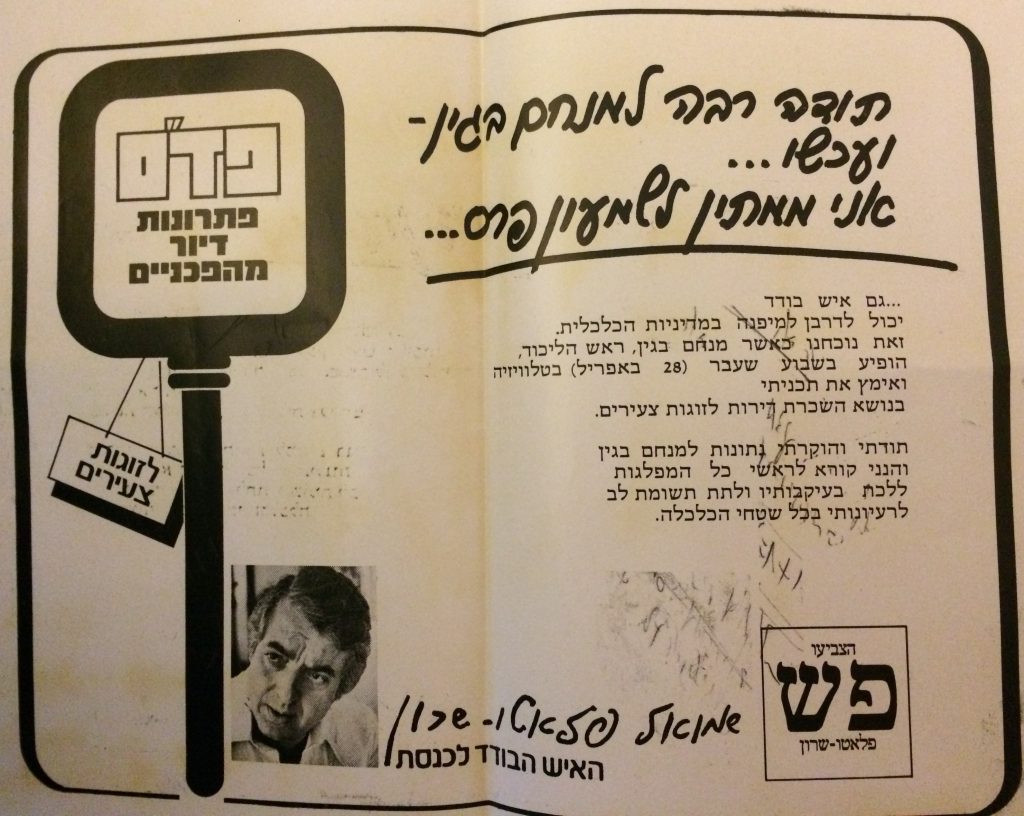

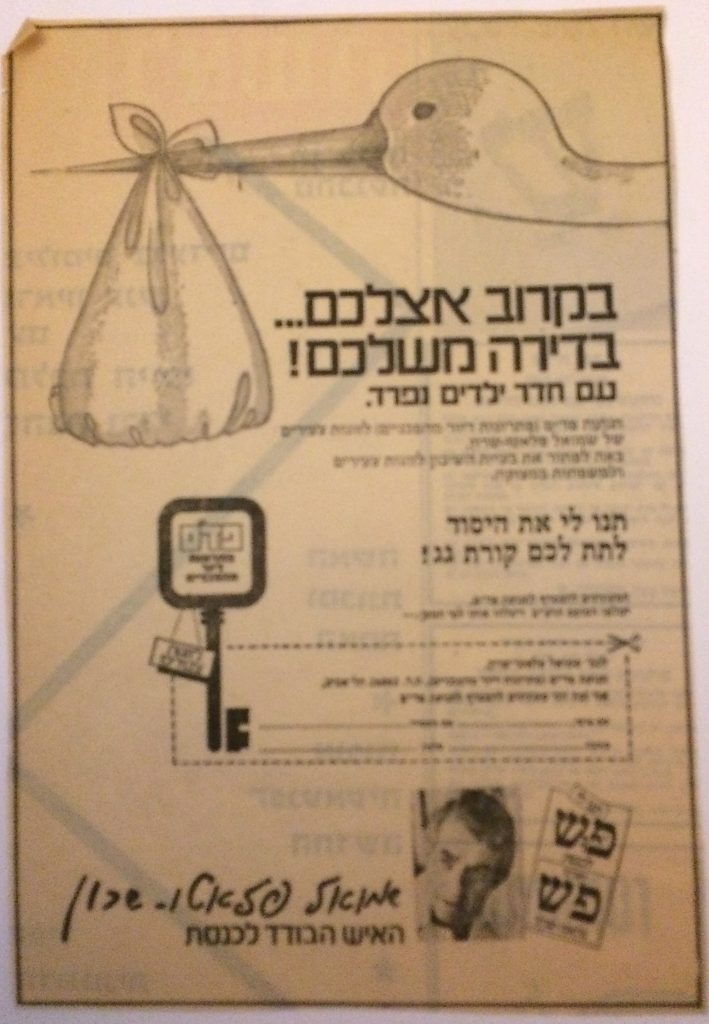

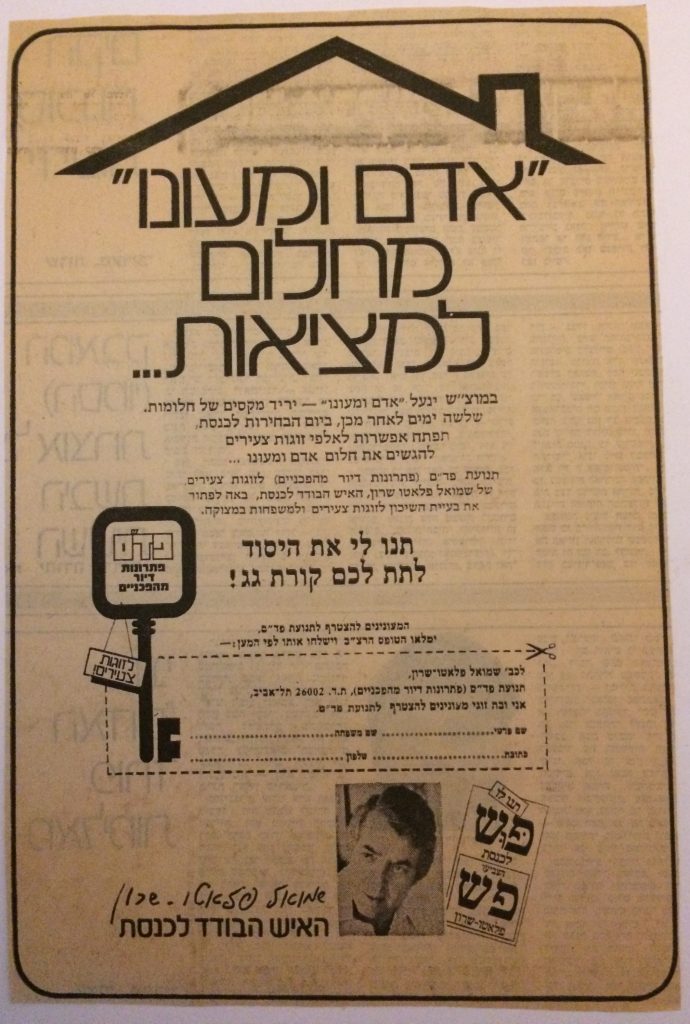

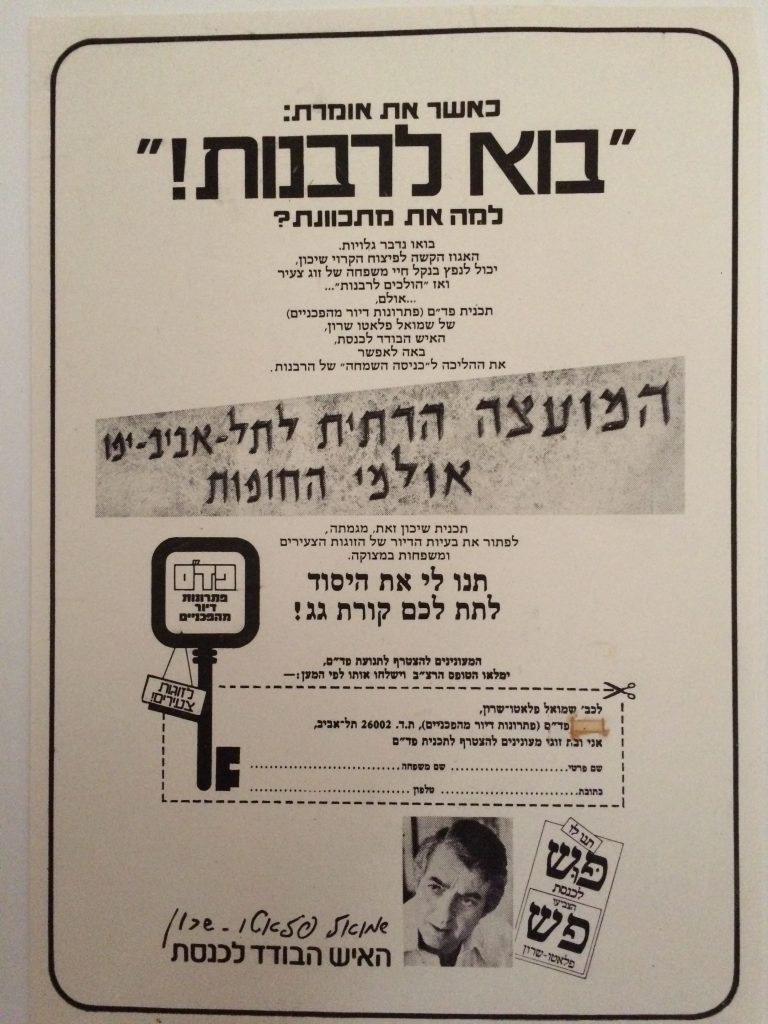

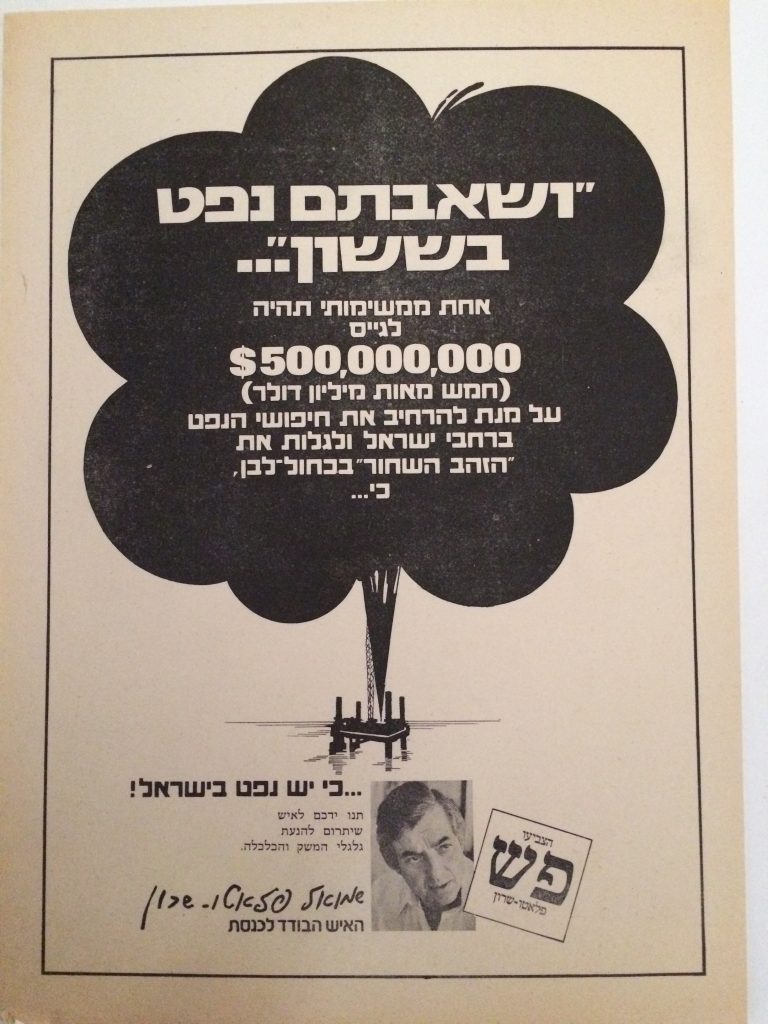

And so, Pommy, a seeker of extraordinary challenges, allowed his thoughts to converge on this new frontier. A torrent of ideas, raw and unfiltered, surged through his mind—a testament to a creative brilliance molded by years in the trenches of journalism. With the clock ticking, Pommy dove into the fray, a maestro orchestrating Sammy's political symphony. Ideas, like streams of consciousness, flowed from Pommy's fertile mind, crafting a campaign that danced on the tightrope of societal issues, championing the cause of newlyweds and the downtrodden.

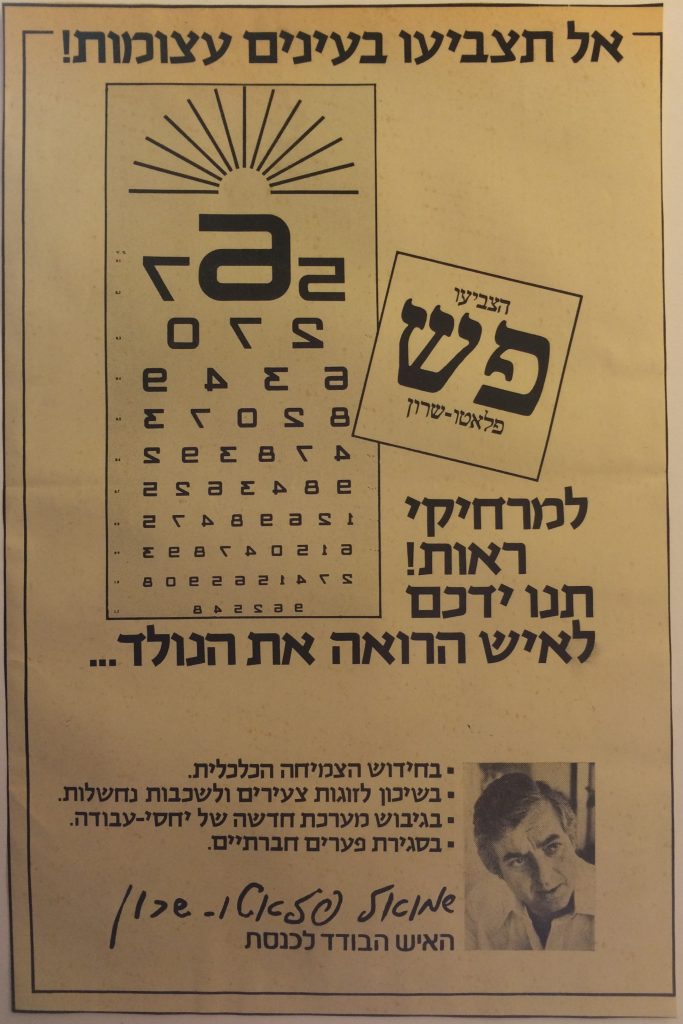

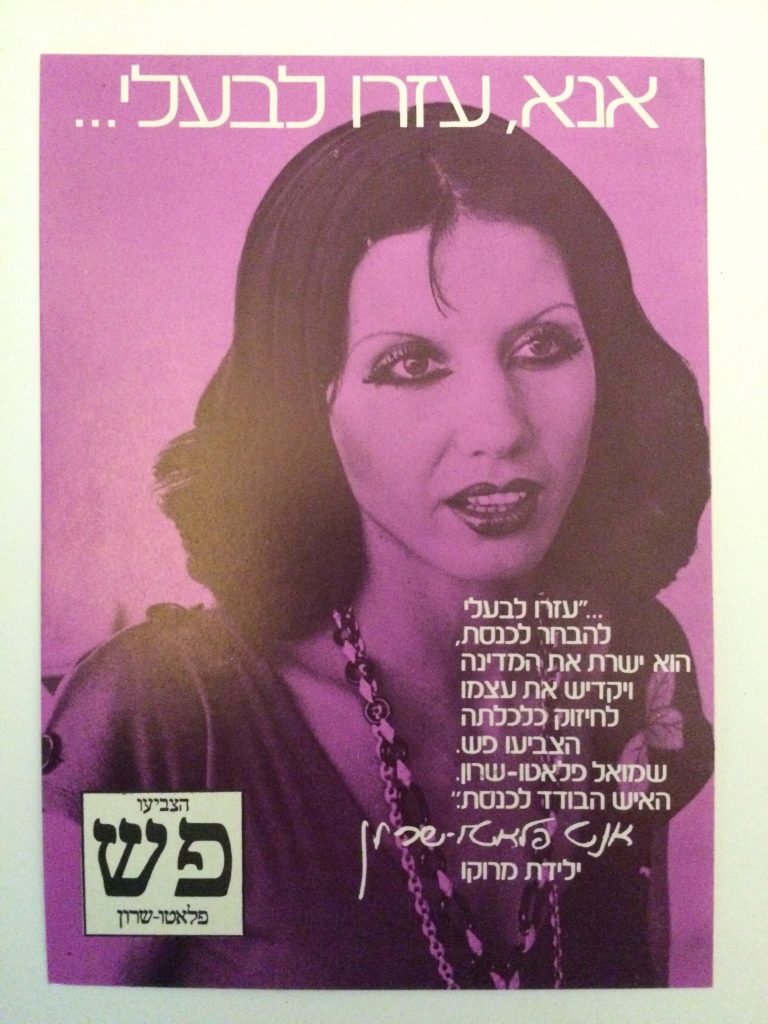

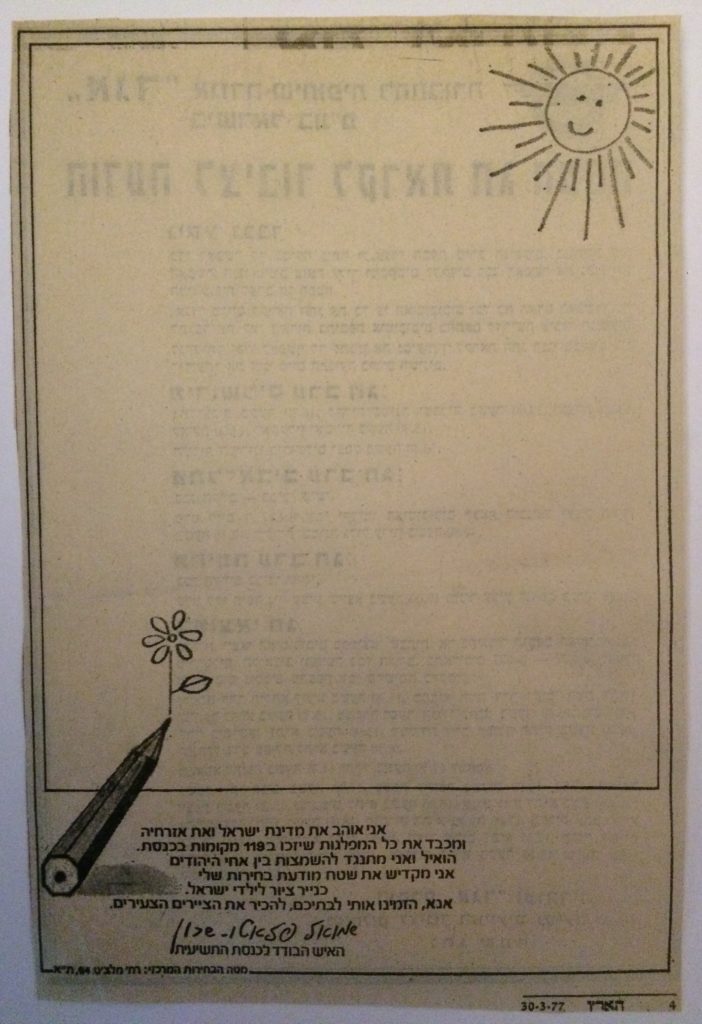

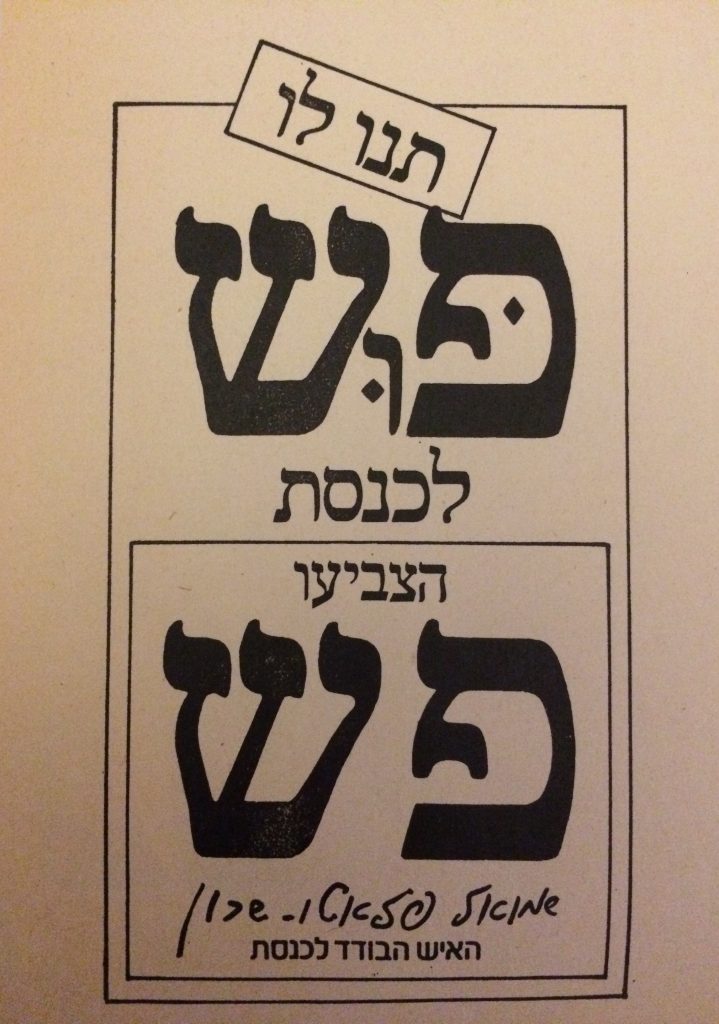

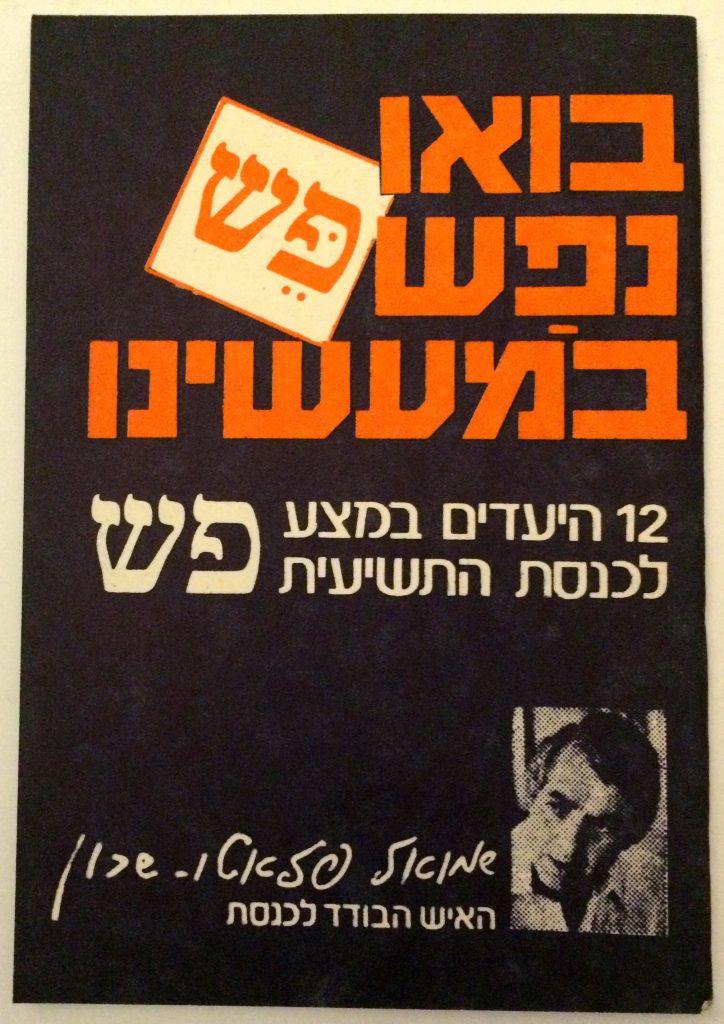

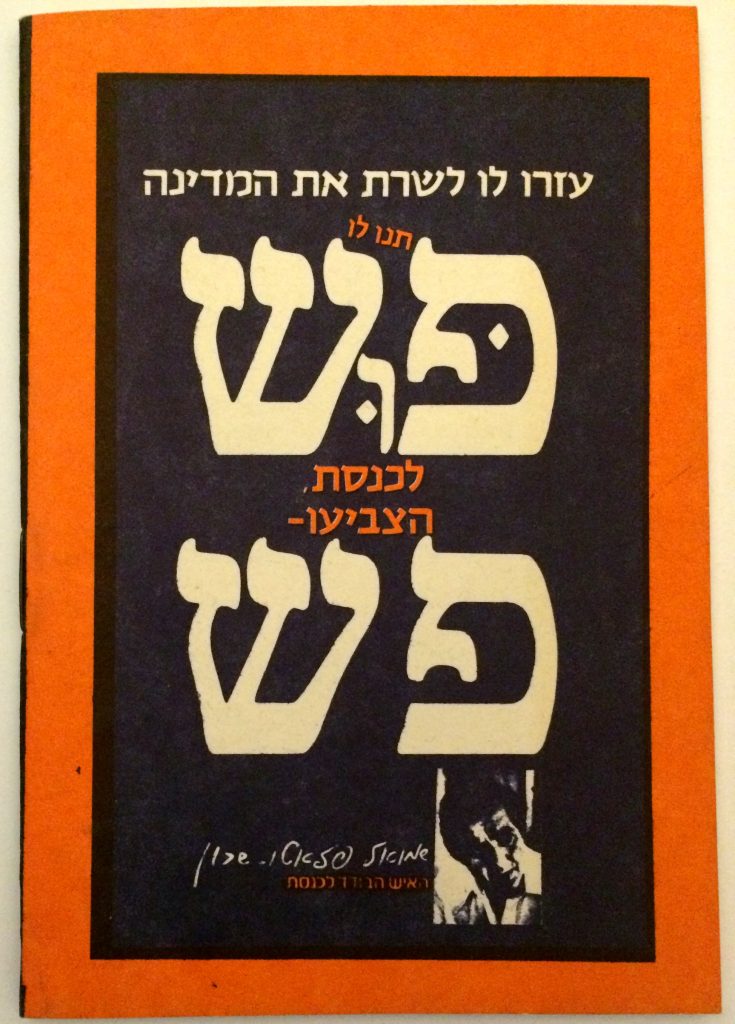

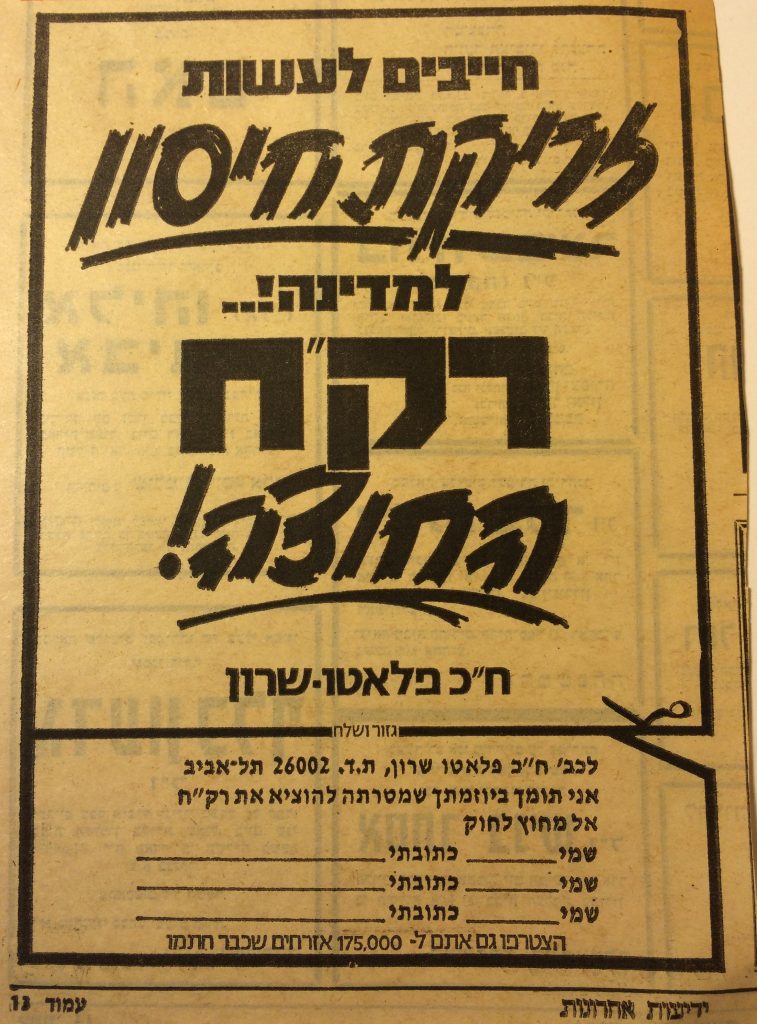

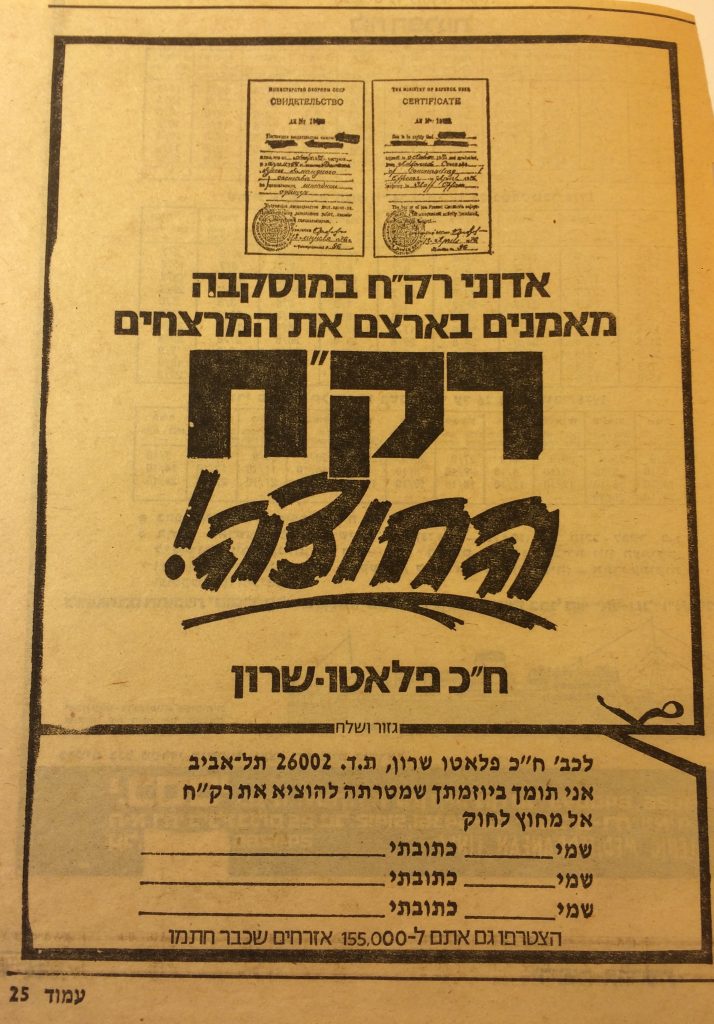

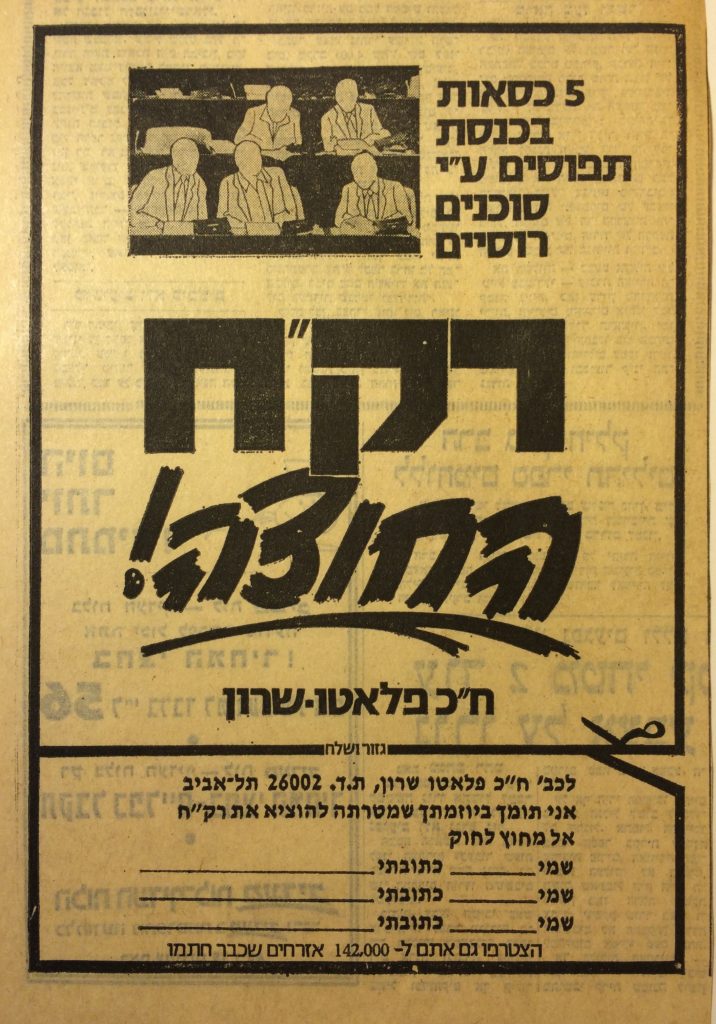

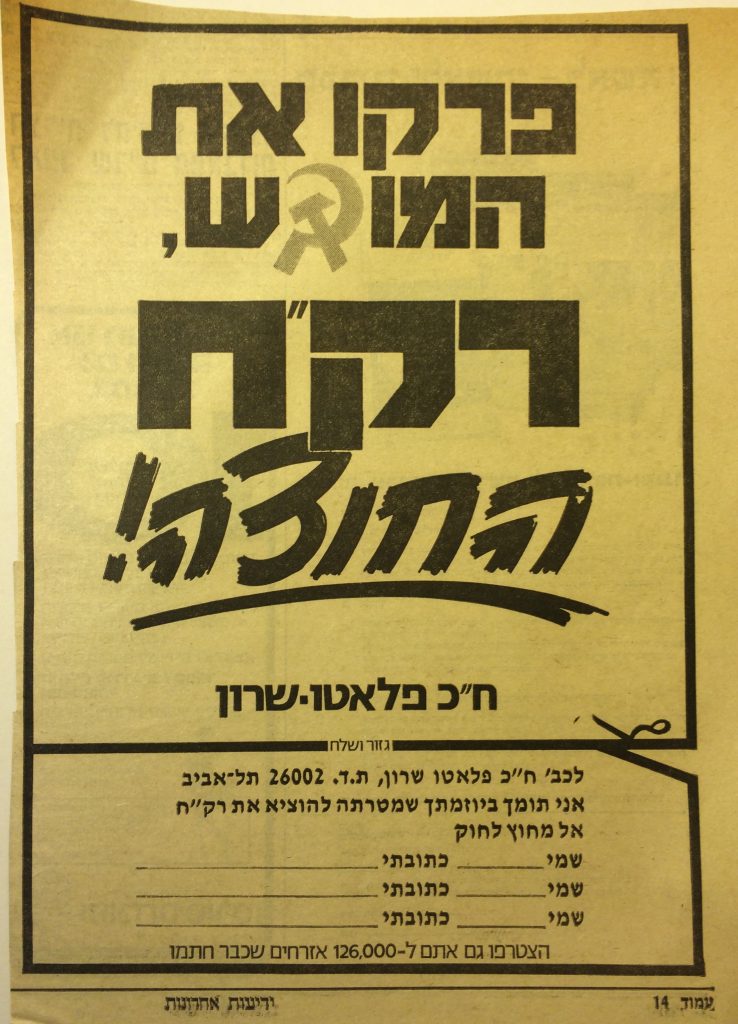

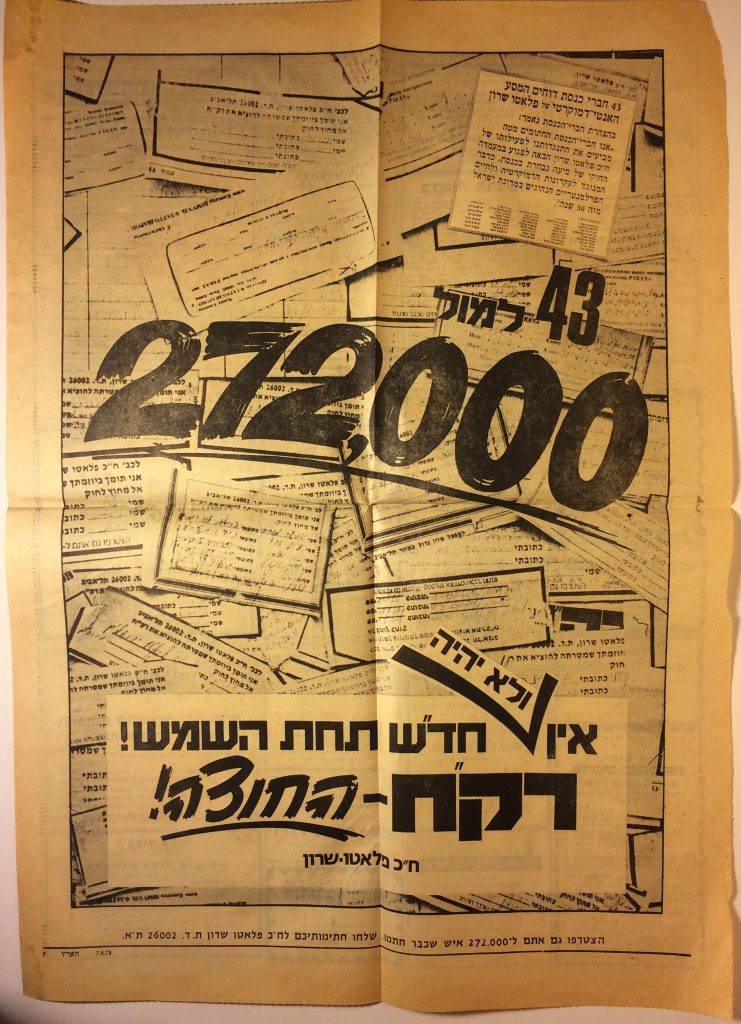

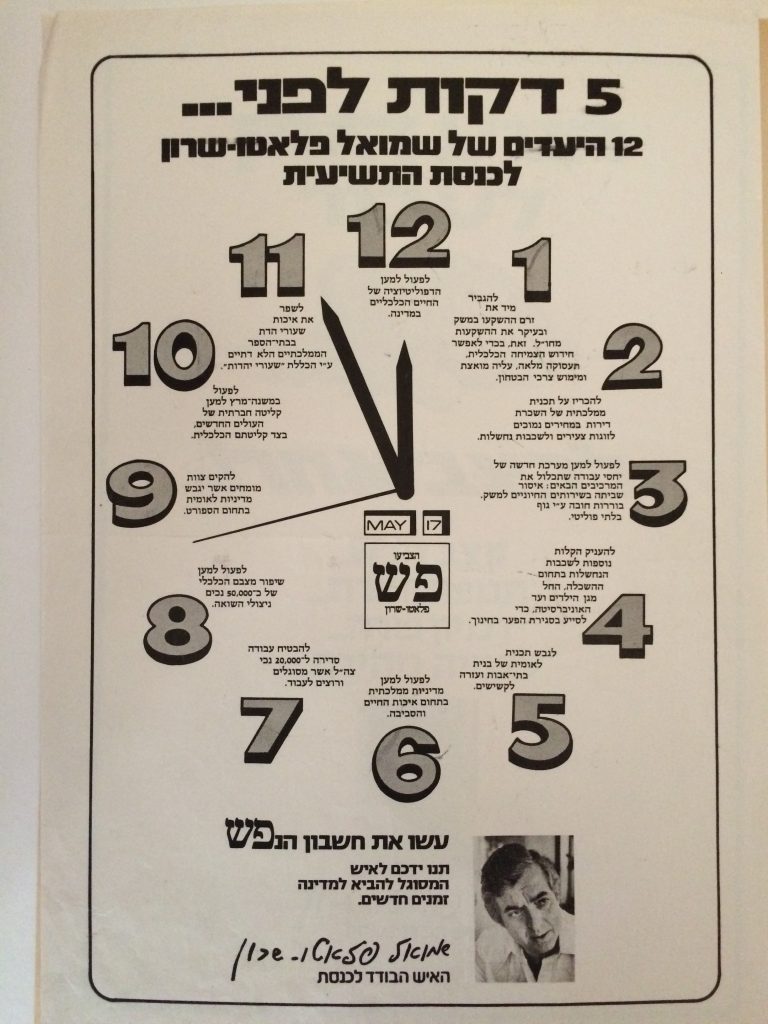

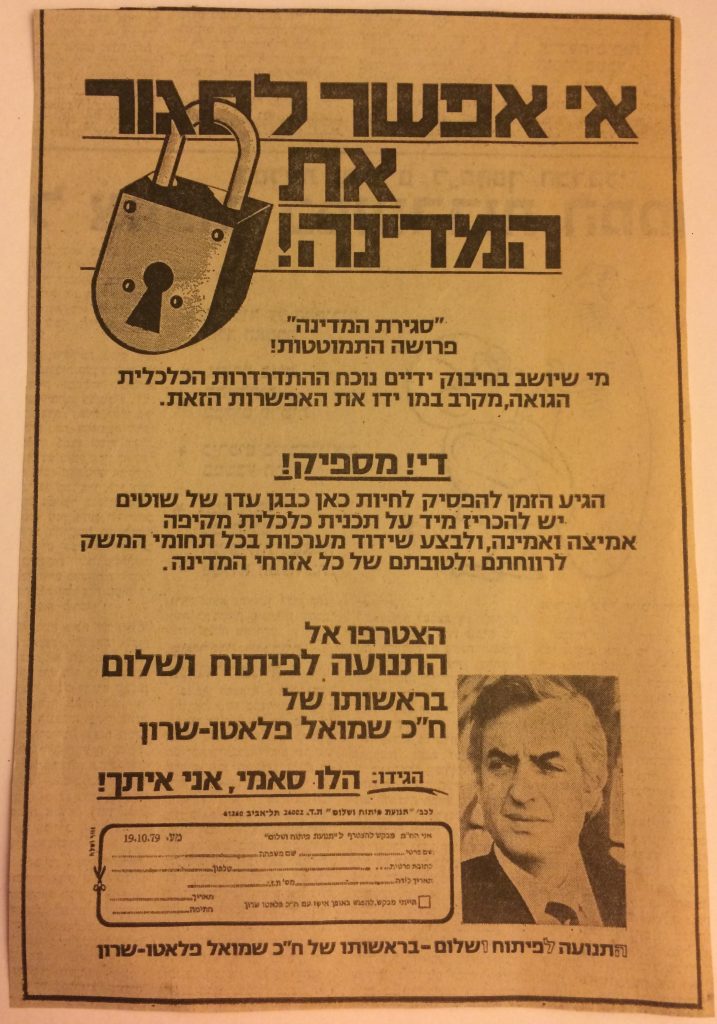

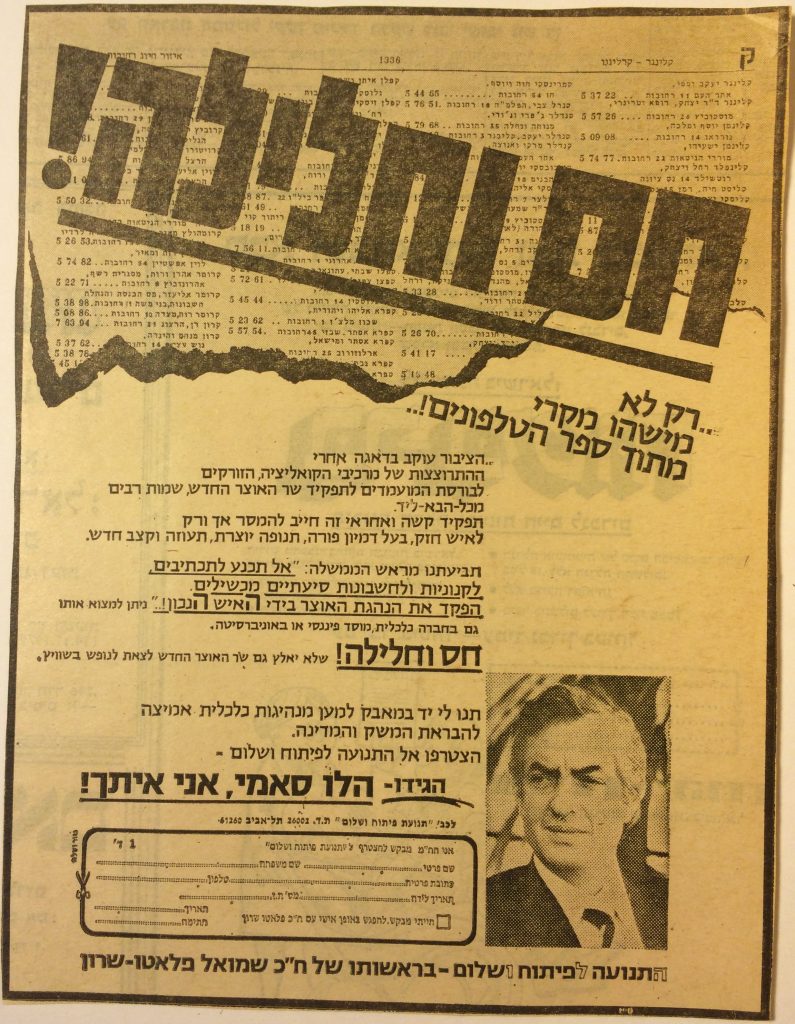

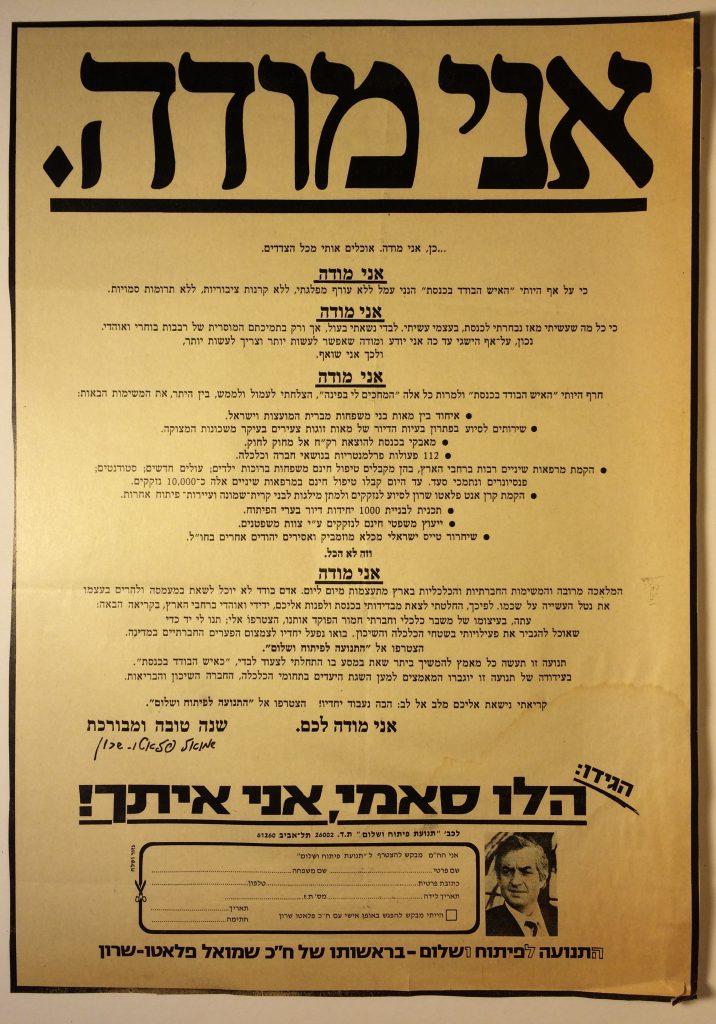

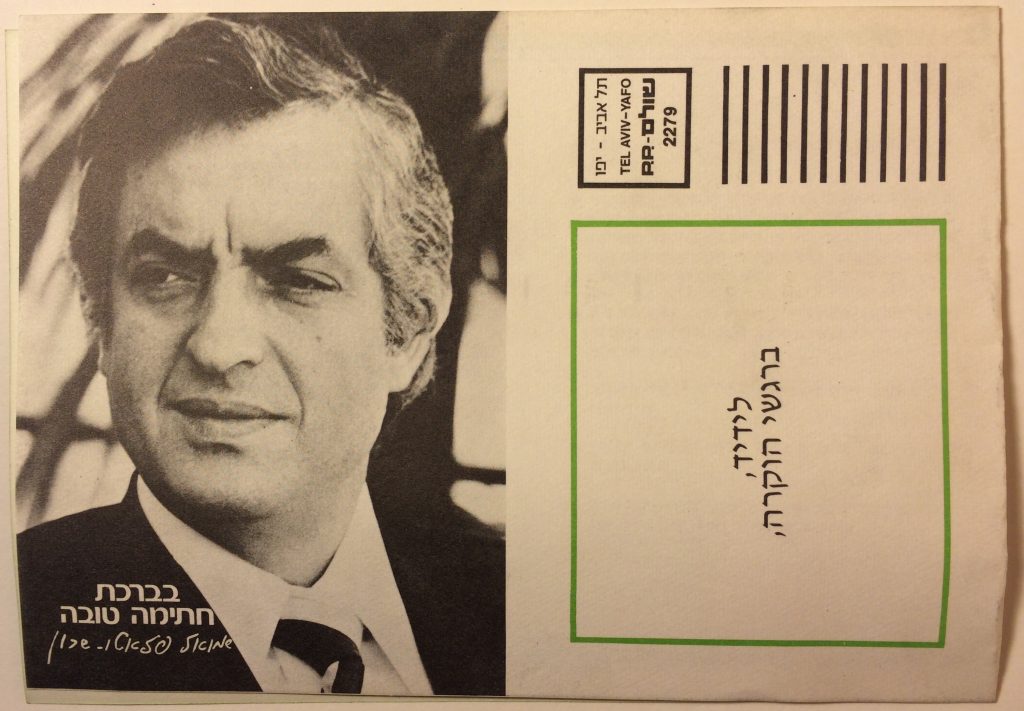

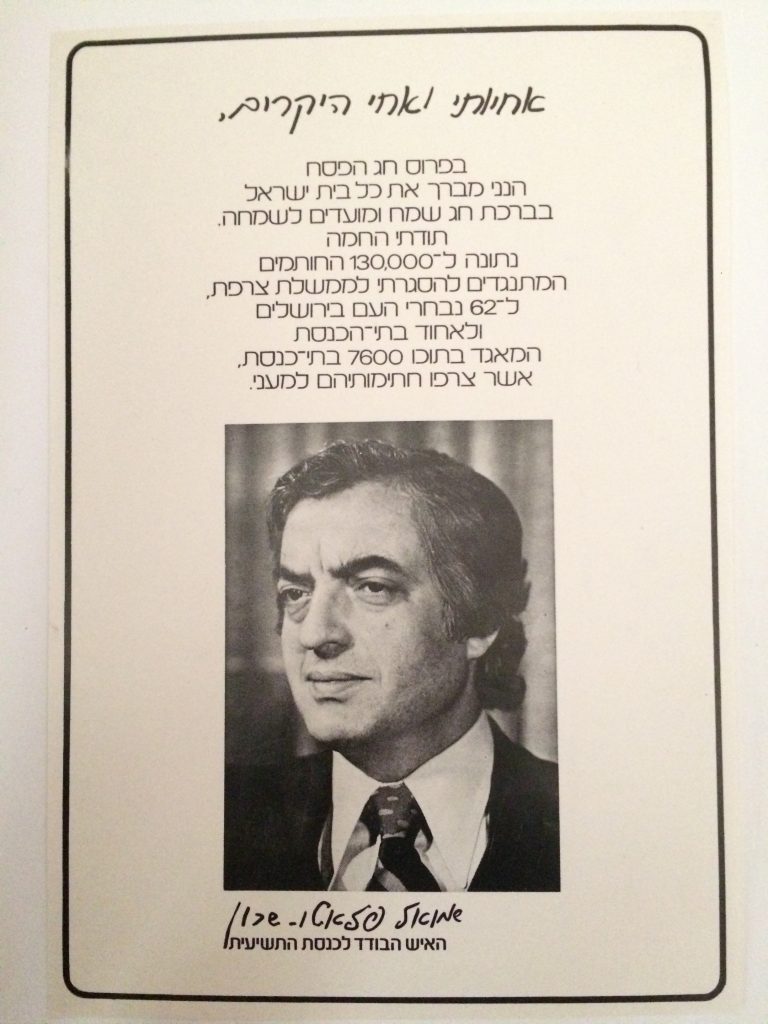

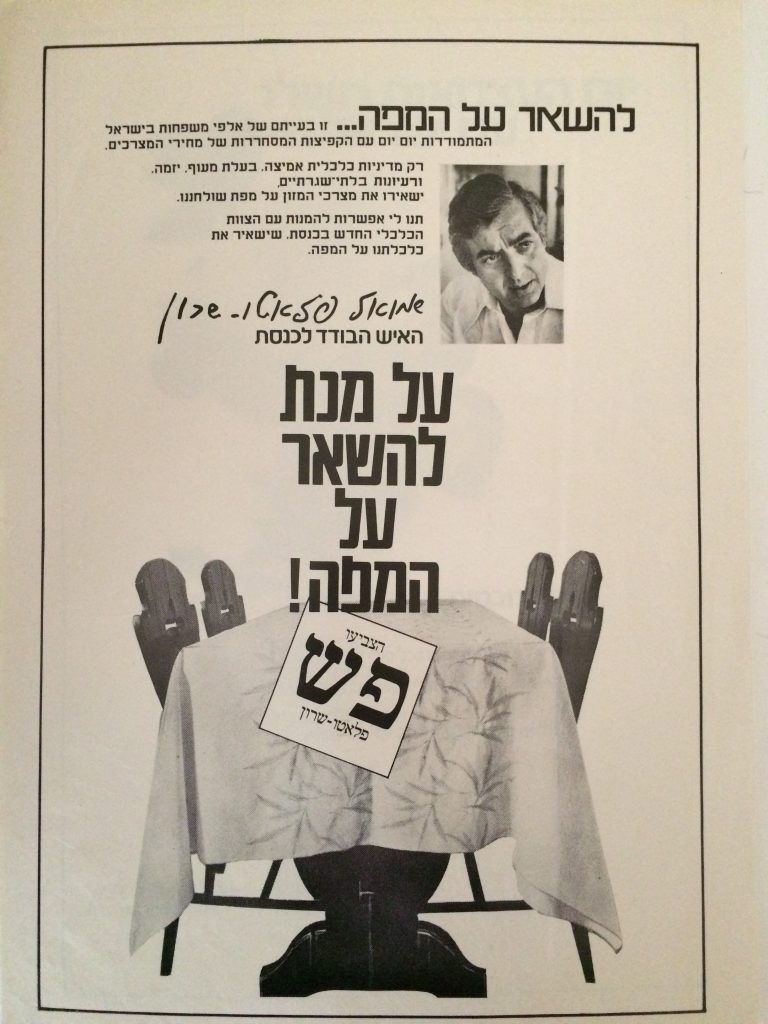

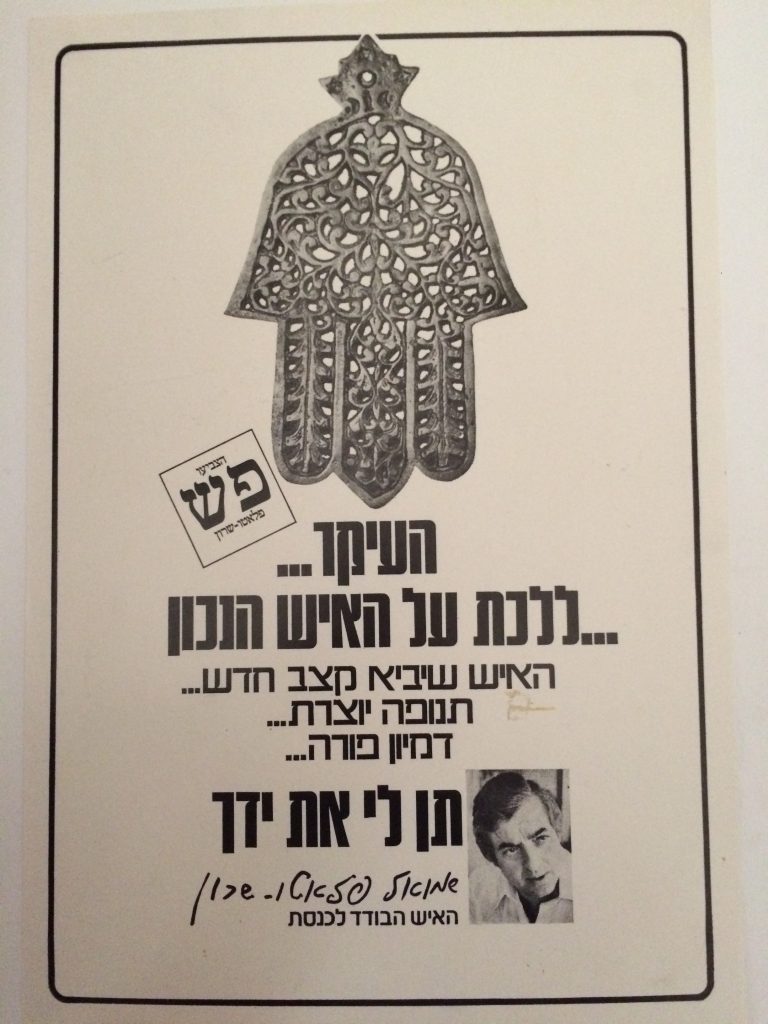

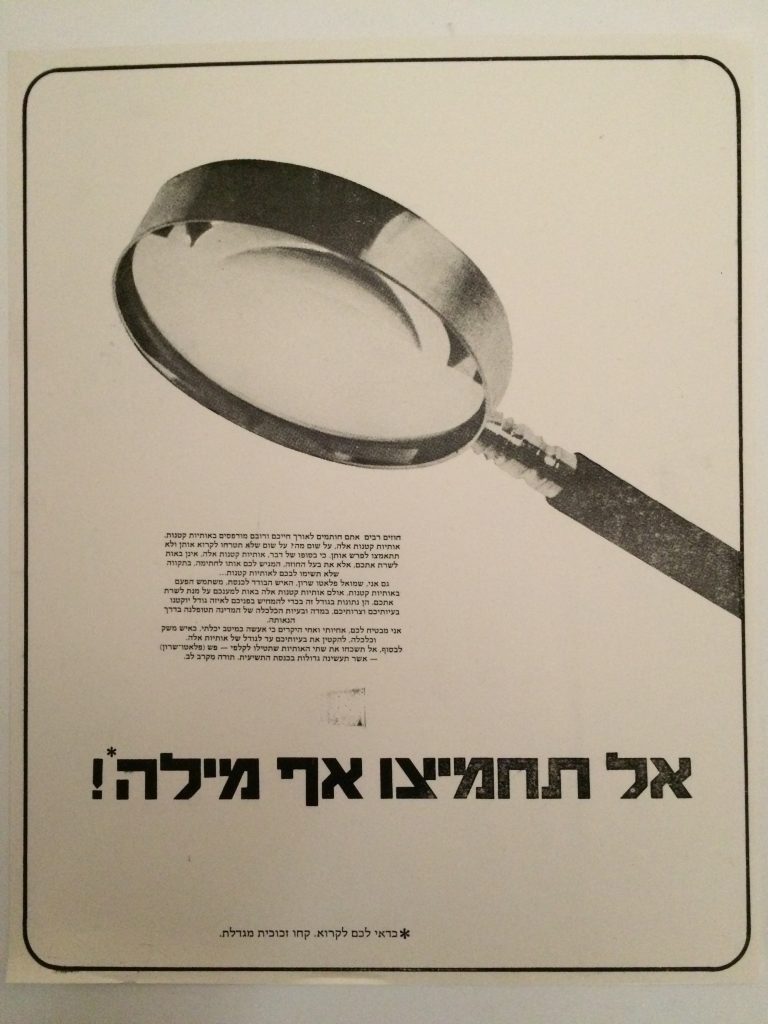

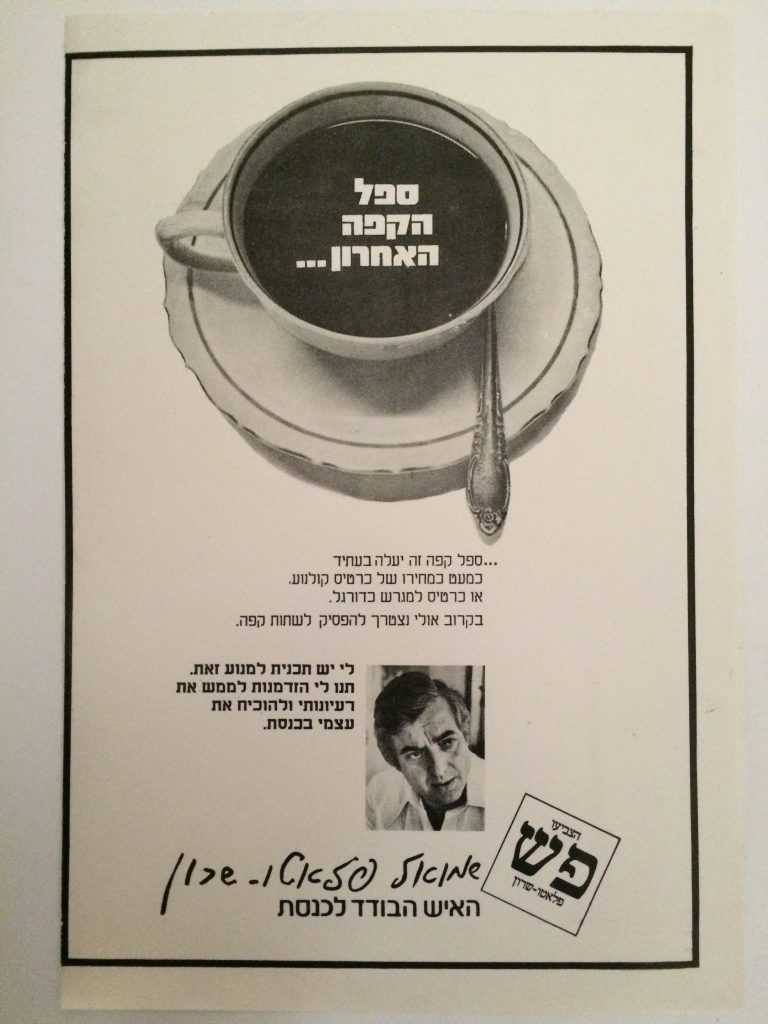

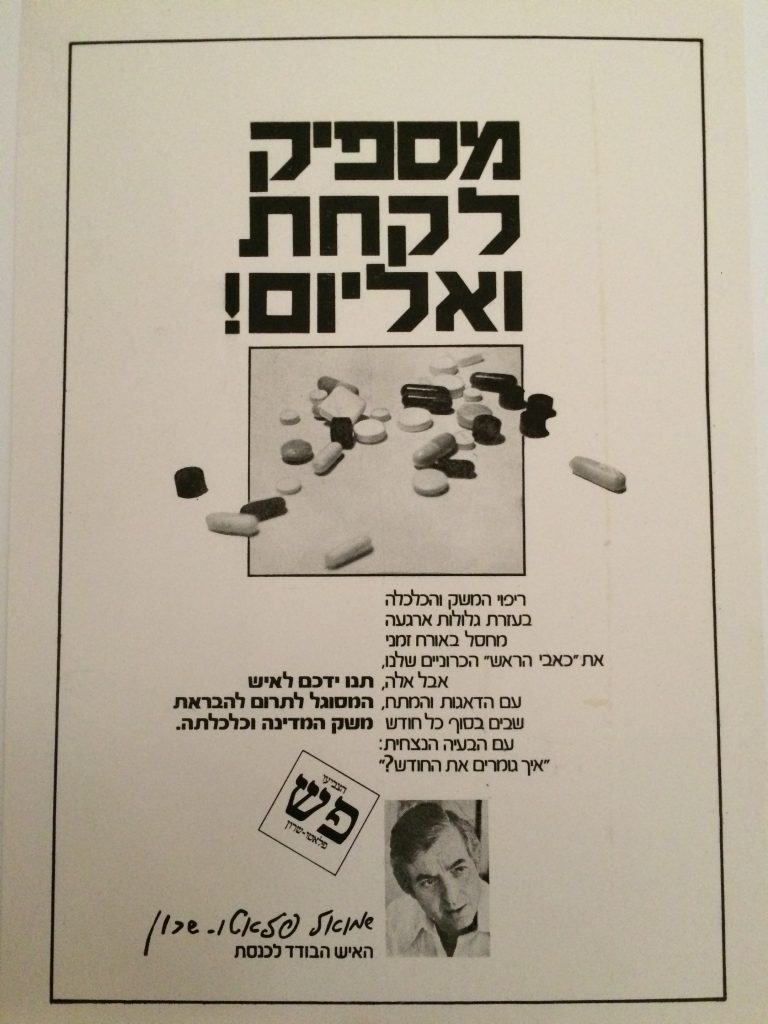

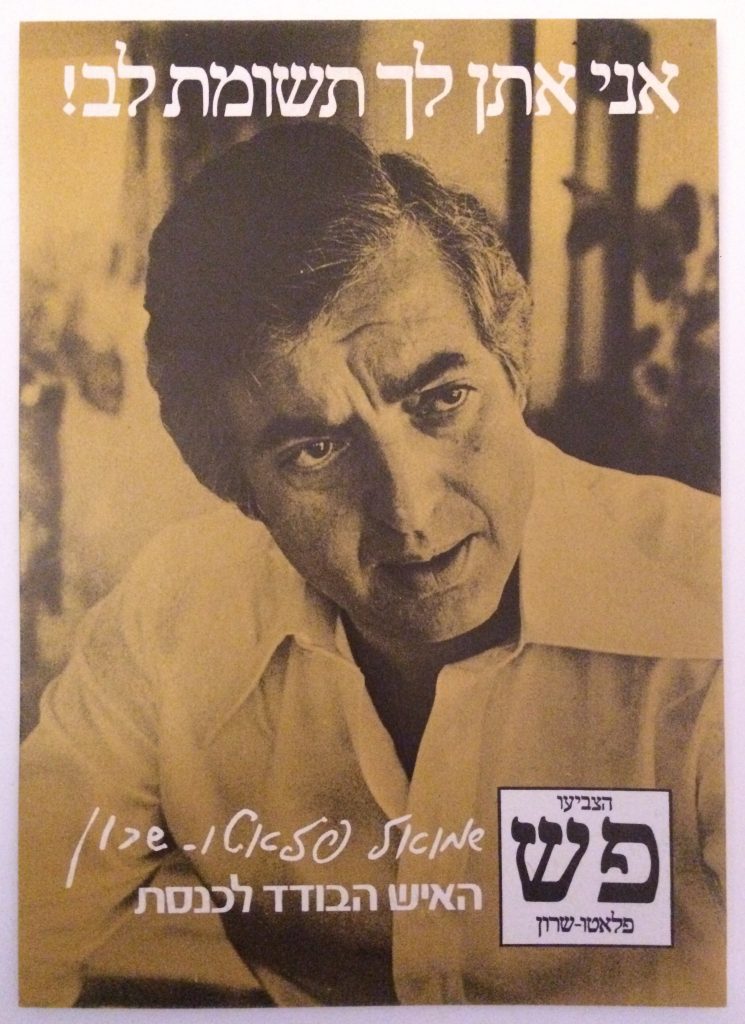

A political party was born, baptized "development and peace," its Hebrew initials, Pay/Shin, mirroring Flatto Sharon's own monogram. The pulse of the nation became Pommy's muse, his daughter Etti an accomplice in the visual language of this political tapestry. Objects were captured in photographs, developed in the darkroom adjacent to Pommy's sanctum, and seamlessly embedded into the ads that adorned the public sphere. Sammy's visage, along with his wife Annette's, emerged from the alchemy of lens and darkroom, shaping an iconography that etched itself into the collective consciousness.

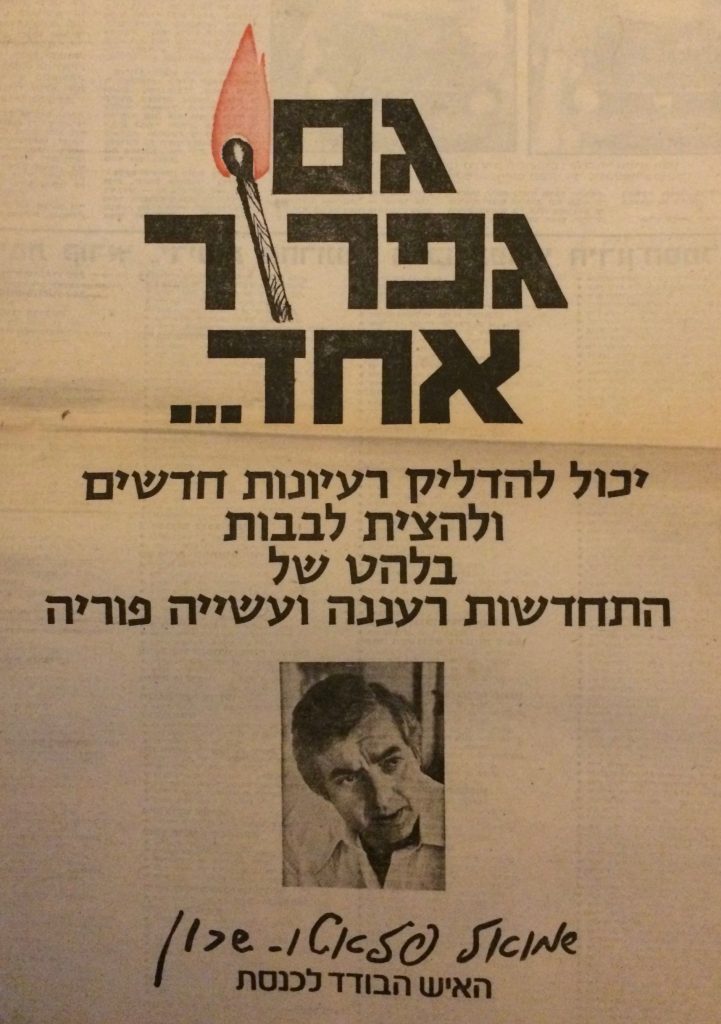

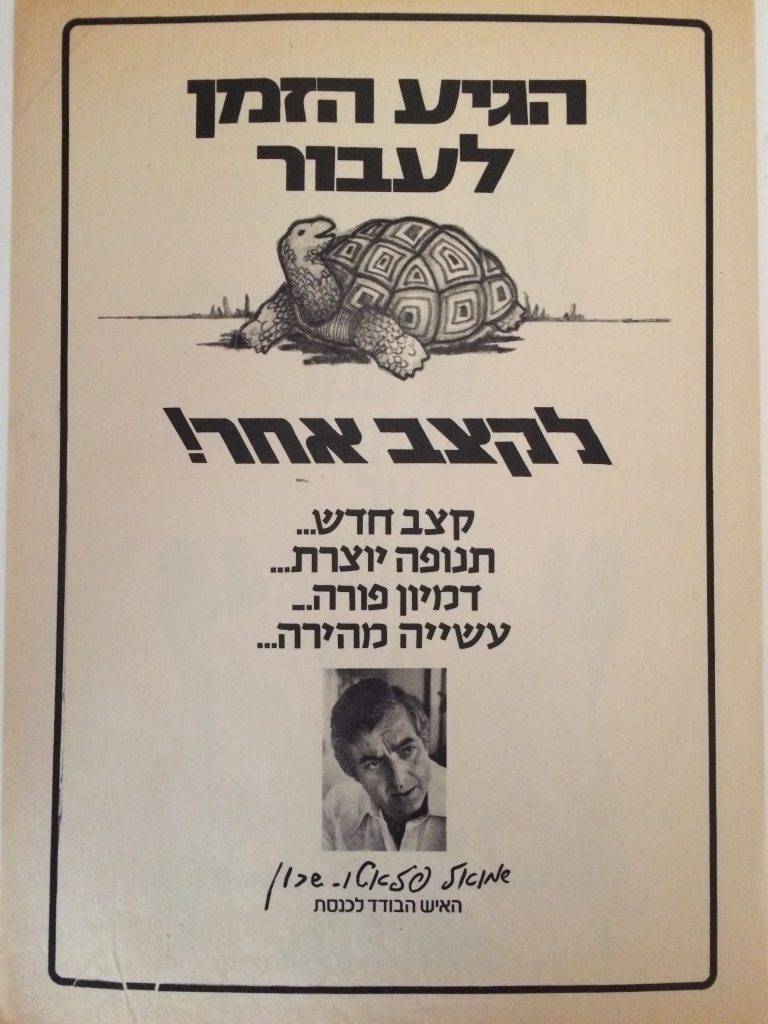

"A Lone Man," proclaimed the slogan—a beacon summoning empathy and solidarity. Pommy painted Sammy as a Jew persecuted by the French legal apparatus, leveraging public sentiment in a dance with France's obstinacy over the extradition of Abe Daoud, the Palestinian mastermind behind the Munich Olympic massacre.

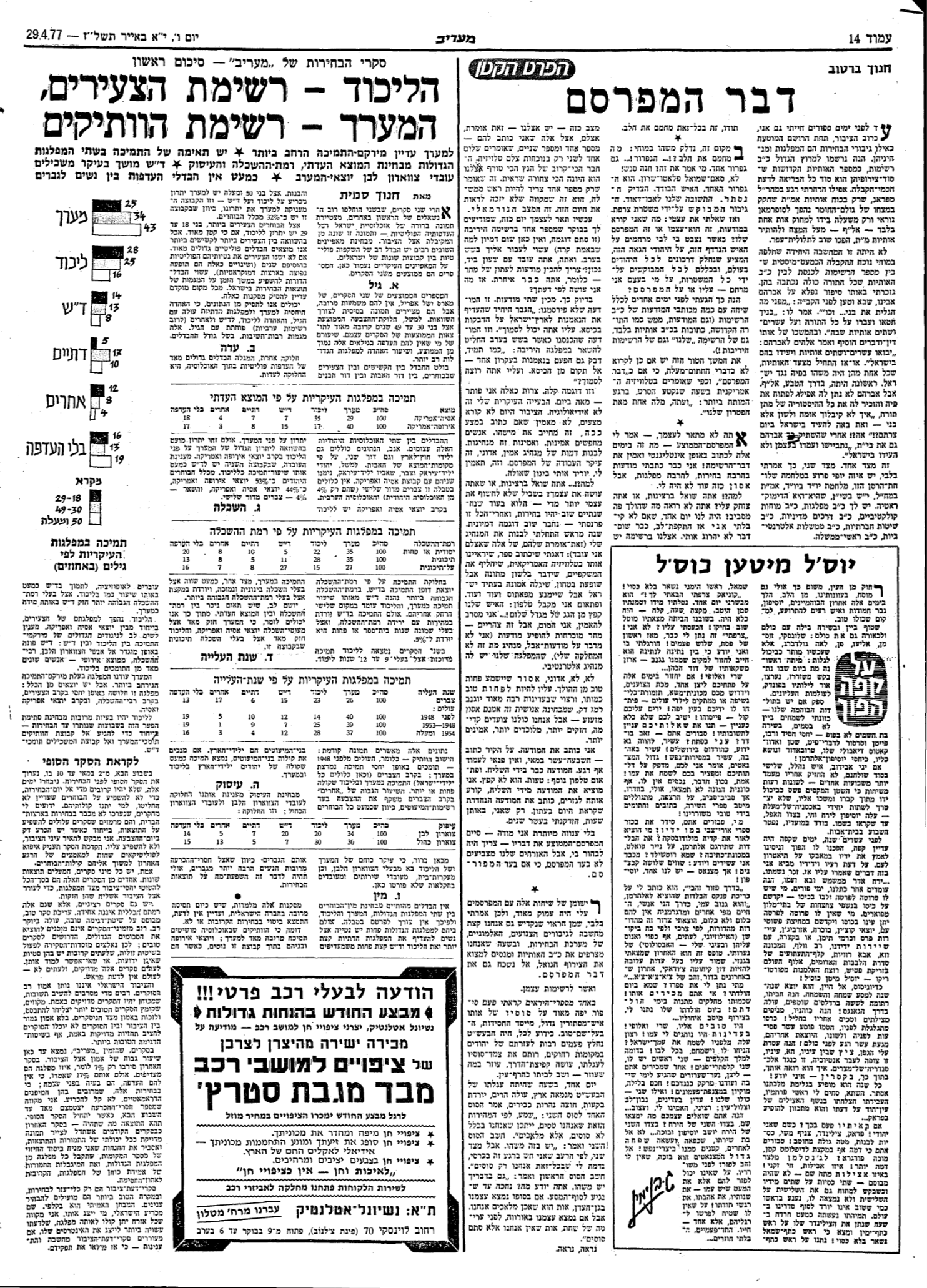

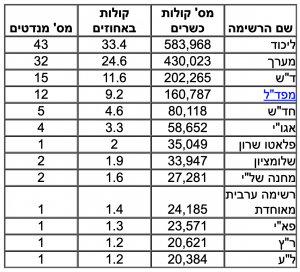

The ninth Knesset election became the stage for Sammy's triumph. 30,594 votes—a chorus of support that reverberated louder than the political symphonies of his contemporaries. A success measured not just in numbers but in narrative, as Flatto-Sharon outshone even Ariel Sharon's newly formed party, Shlomzion, securing two seats with 2% of the vote.

In the swirling maelstrom of the campaign, a pivotal moment emerged like a lone figure on a dimly lit stage. It was the juncture where Sammy, sensing the currents of victory wrapping around him like a warm cloak, turned to his confidante Pommy. Their friendship, forged in the crucible of political machinations, had become the stuff of legend in the backrooms and smoke-filled chambers. In a quiet corner of the campaign headquarters, Sammy, his eyes glinting with the sheen of impending triumph, broached a proposition to Pommy that would forever etch itself into the annals of their shared history. With an air of camaraderie, Sammy extended an invitation, a golden ticket to the political circus. He urged Pommy, the words dripping with sincerity, to stand alongside him as a second candidate. A proposition that promised not only political accolades but also the deepening of their bonds, as friends turned comrades in the arena of power.

Yet, Pommy, the wordsmith and provocateur extraordinaire, declined with a nonchalant grace. The air hung heavy with unspoken truths as he explained his role as a publicist and a weaver of political satire. A "free agent," he declared, untethered by the constraints of a political persona. His allegiance lay not with the rigidity of party lines but in the fluidity of ideas, a dance of words that knew no partisan boundaries. In the end, Sammy may have stood victorious on the podium of politics, but Pommy, the wordslinger, remained true to his craft.

A Lone Idea-Man

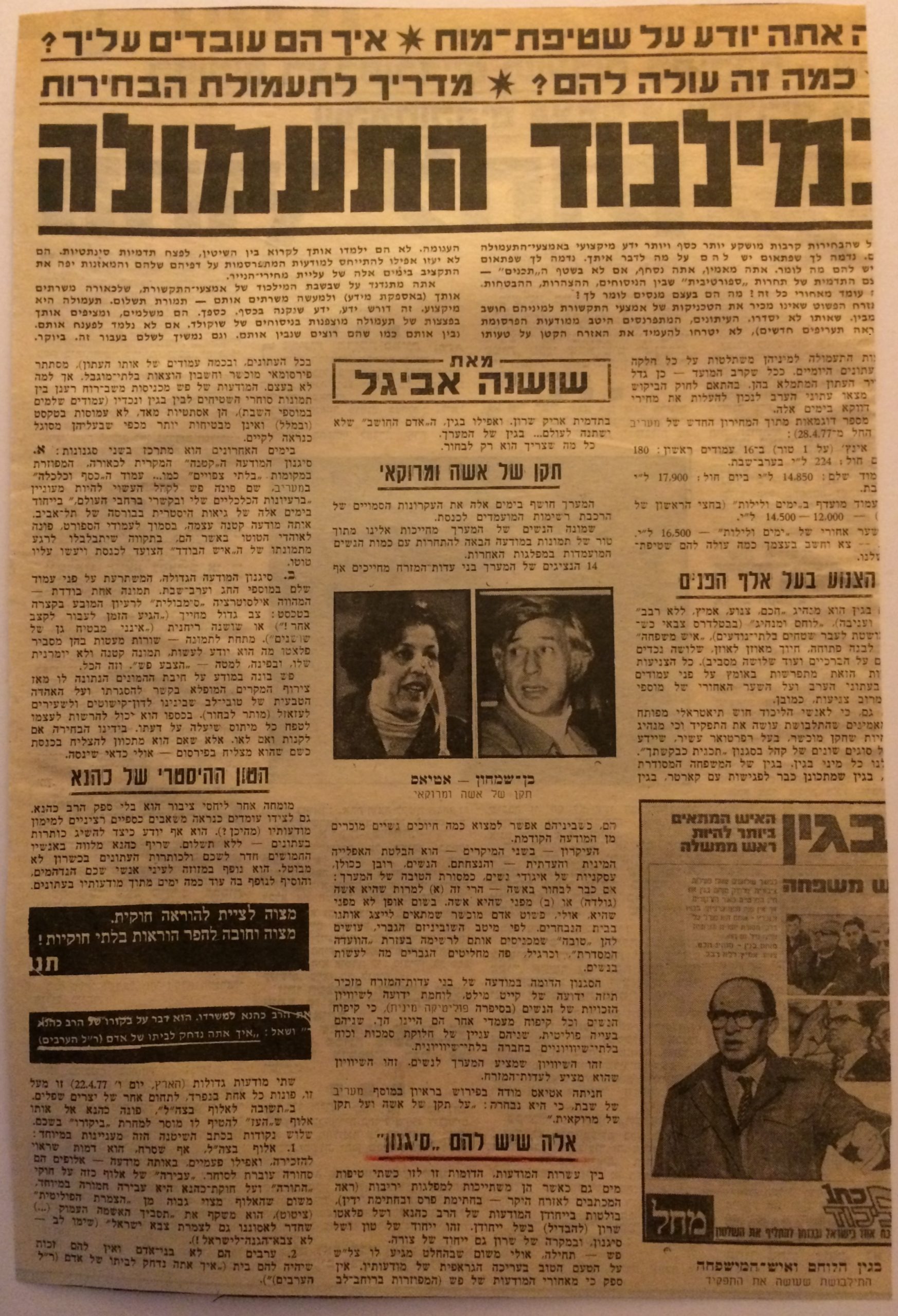

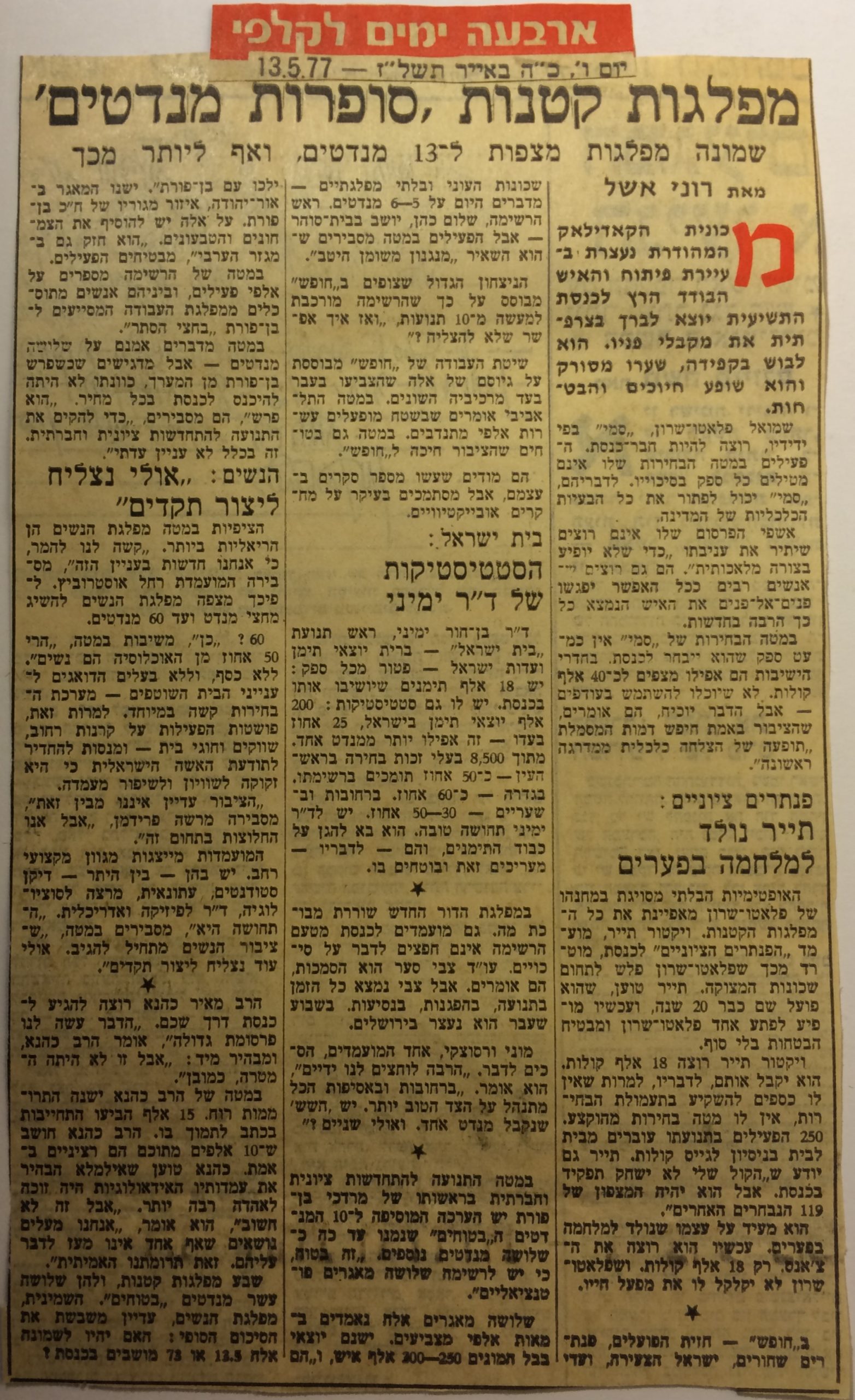

In the political circus of 1977's Knesset elections, where promises were as fleeting as the gusts of desert wind, one man stood singularly poised at the center, orchestrating the grand spectacle – the Lone Man of Ideas, Moshe, Pommy, Hadar. In the ink-stained pages of Ronnie Eshel's article, "Small Parties, Counting Mandates," the narrative of Flatto-Sharon's campaign unfolded like a carefully scripted drama. "His Advertising Wizards …" (Four Days to the Ballot Box, May 13, 1977).

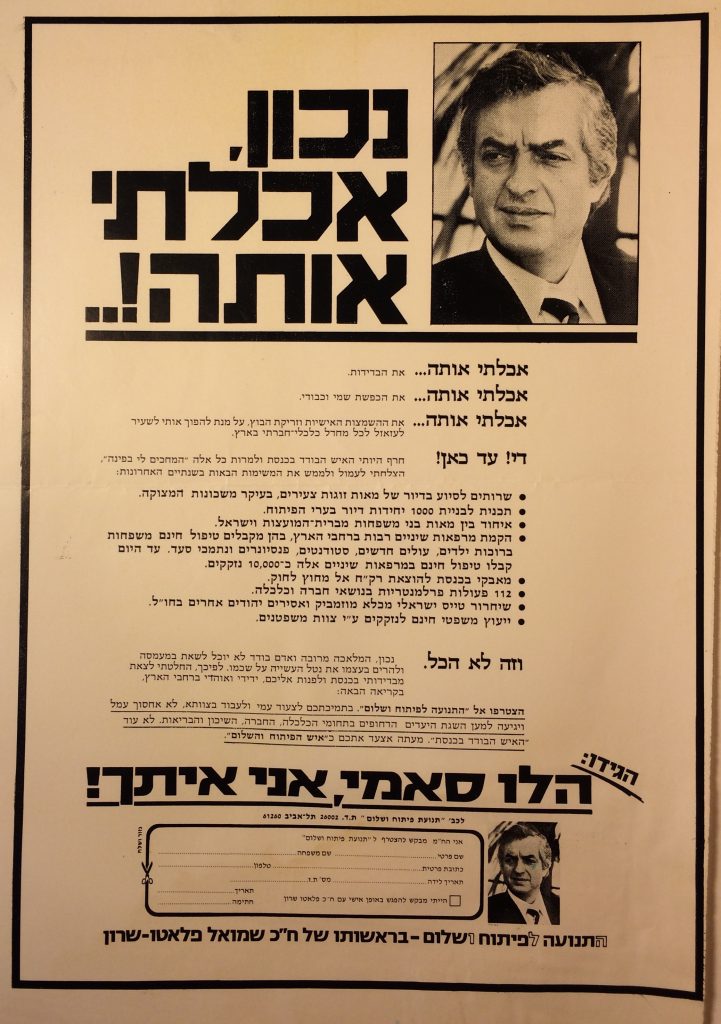

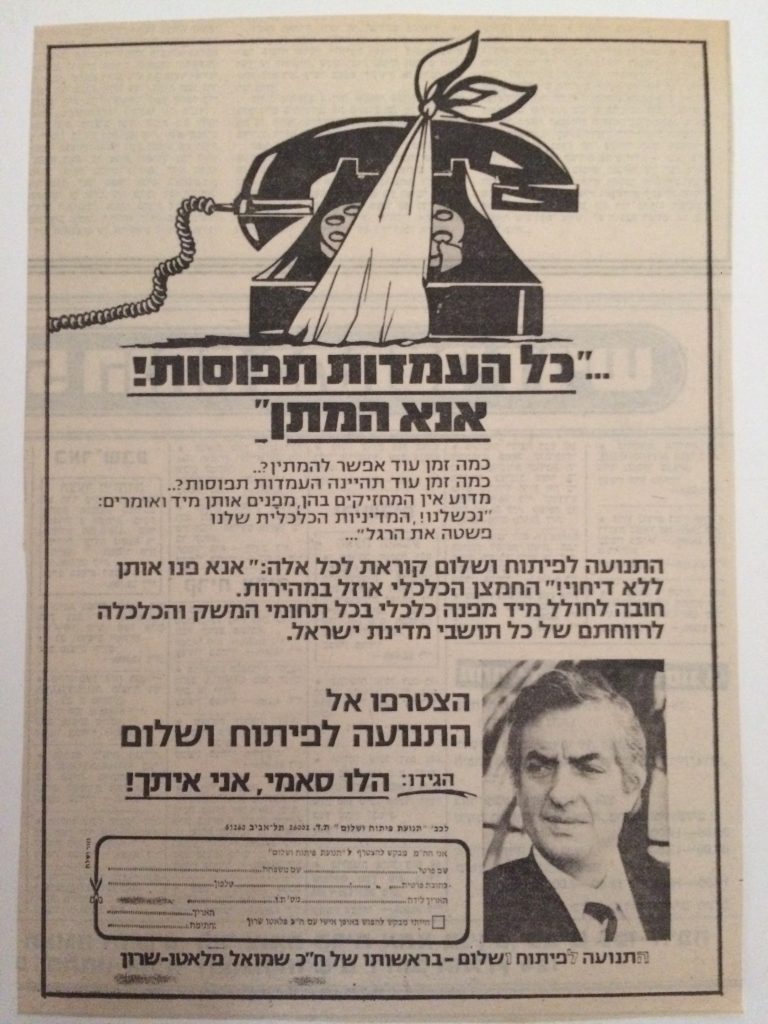

Prof. Jeremiah Yuval, in his in his penetrating analysis, dissected the strategic maneuvering of publicists who molded the clay of Flatto-Sharon's public image. The Lone Man to the Knesset (May 13, 1977), he wrote: "Basically, it was the job of the publicists who took on the image of Samuel Flatto-Sharon as a potential Knesset member. Admittedly, they too had to change an image. But, for that matter, they were free to paint their new 'creation' in whatever they thought was attractive. This is to give to the public, who wanted to prevent his extradition to France at all costs, the moral justification for choosing him for the Knesset. They created, on the one hand, an image of a ‘lone man’ – that is, poor, and, on the other, equipped him with ideas that might be absorbed in different sectors of the population.” Yet, as Prof. Yuval astutely noted, the Achilles' heel of this campaign lay in the grandiosity of promises that one lone Knesset member couldn't possibly fulfill.

Shoshana Avigel, a keen observer of culture, dissected the propaganda machinery in her piece, "Propaganda Hook." Amidst the sea of mundane political ads, the distinctiveness of Flatto-Sharon's campaign stood out like a rare gem. There is no doubt that behind Pay/Shin's ads (widely distributed across all newspapers, and in several pages of the same newspaper), lurks a talented publicist and unlimited expense account." Avigel showered praise on the artistry of Pay/Shin, the maestro behind the visuals, who wove a tapestry of aesthetic appeal across newspapers, defying the clichés of political messaging. "But why not?" she continued, Pay/Shin's ads bring a fresh breeze among the carpet dealers' images and [Menachem] Begin's grandchildren (entire pages of the Sabbath newspaper supplement) are aesthetically pleasing, not laden with text (and copy) and no more promises than the candidate is likely to deliver."

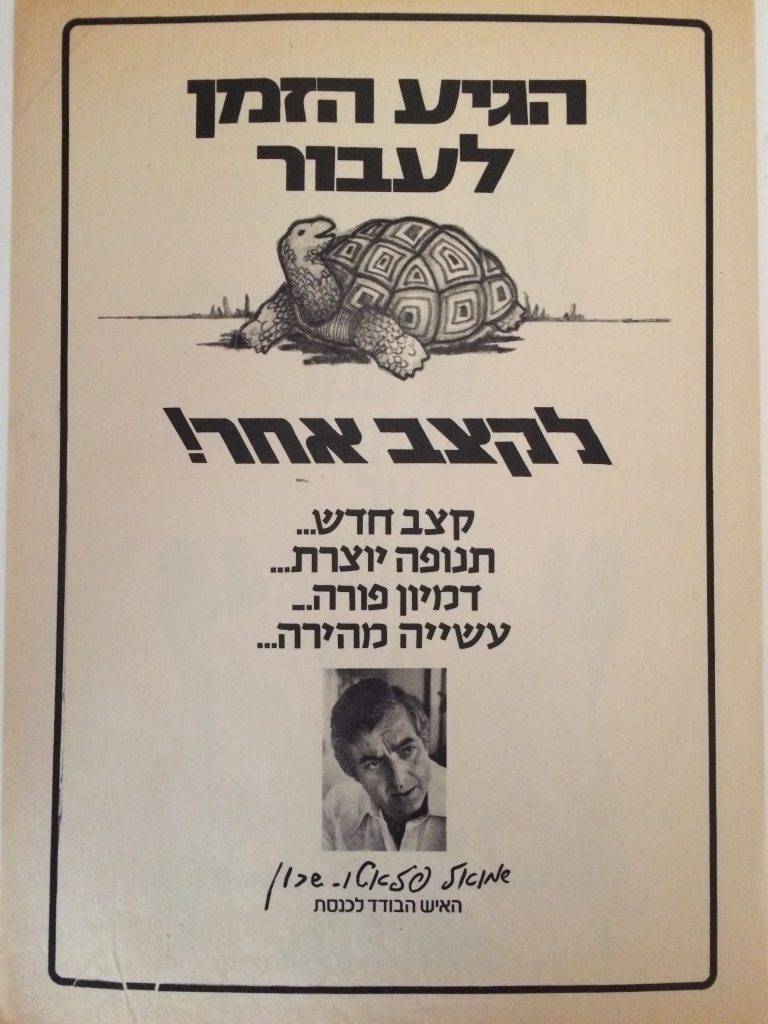

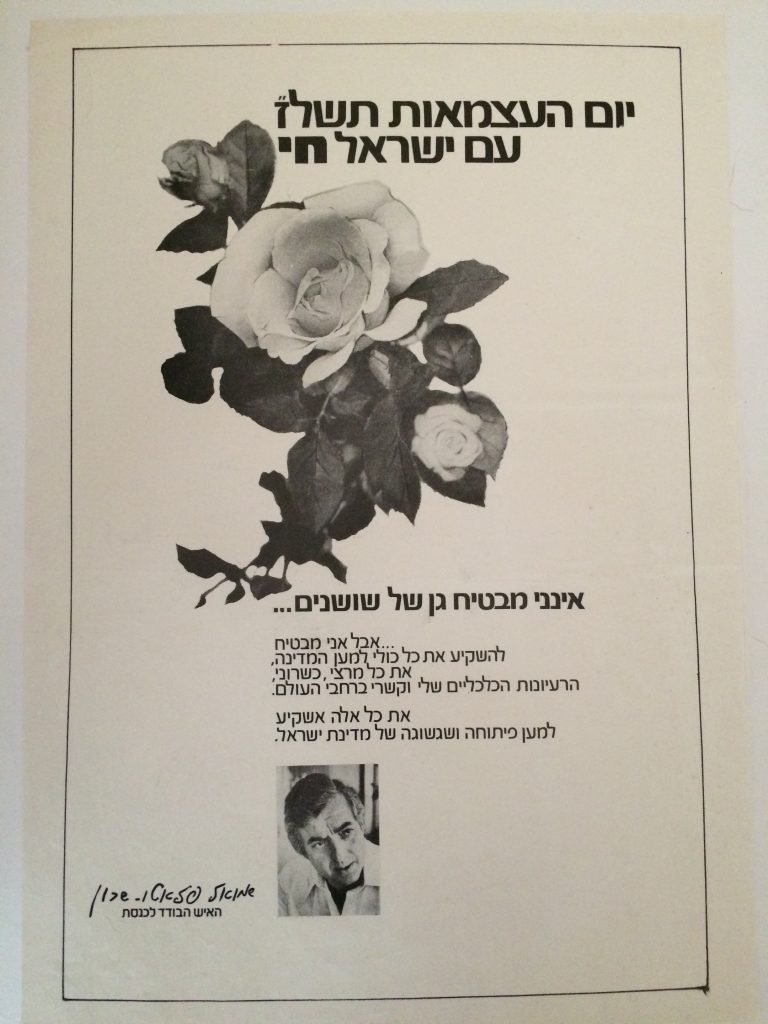

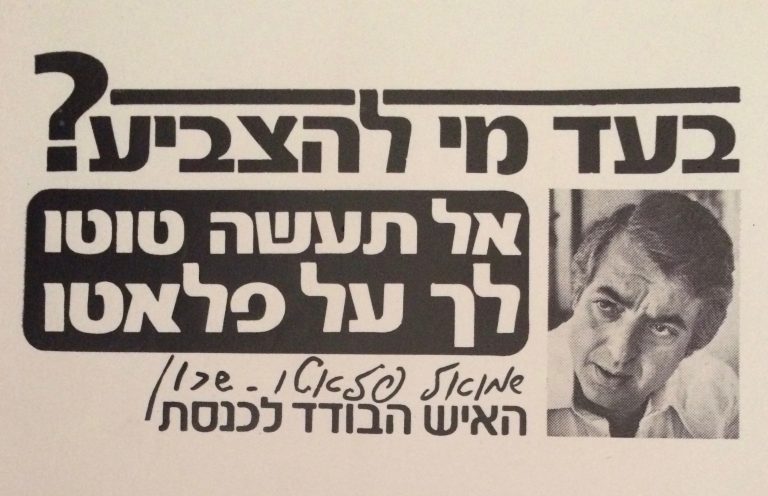

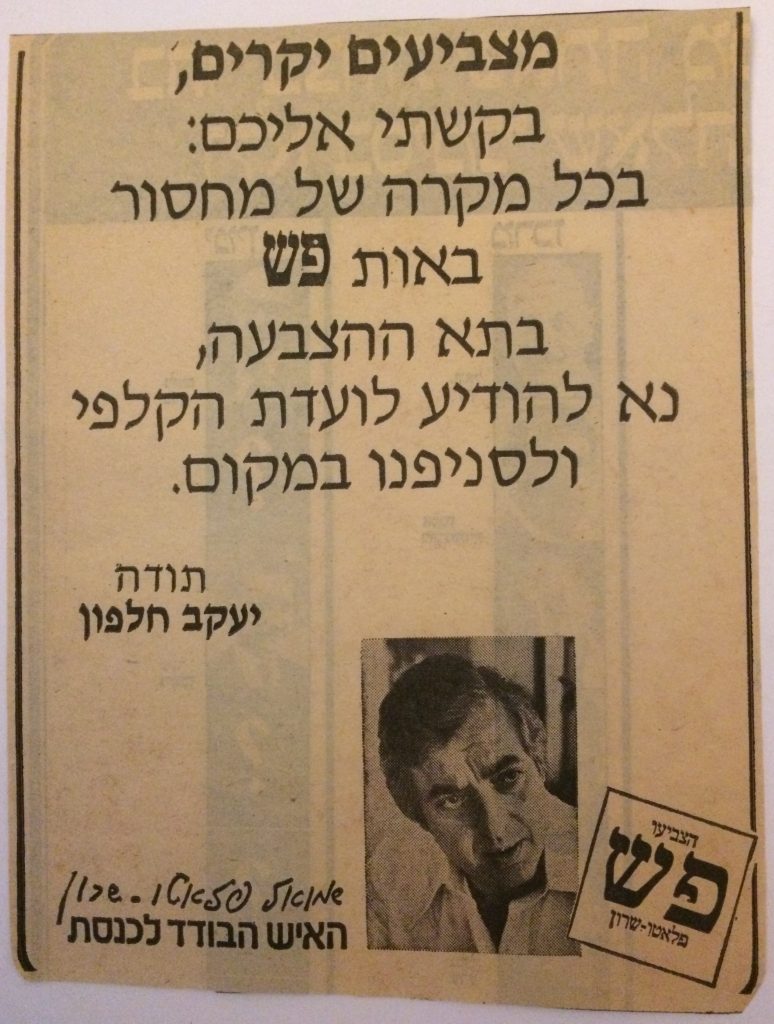

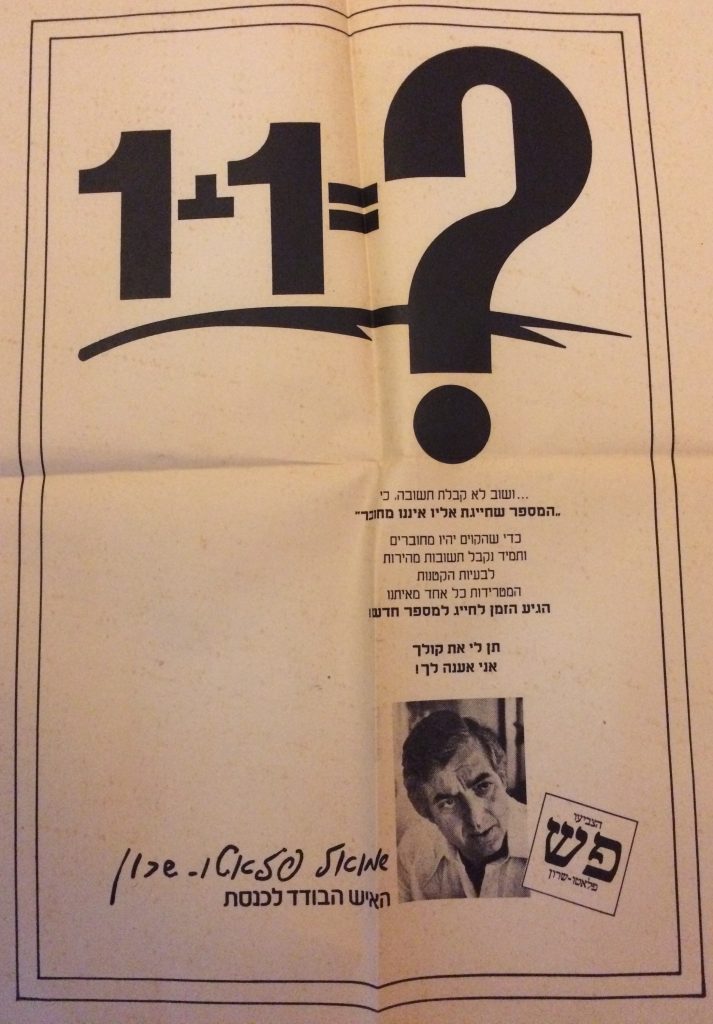

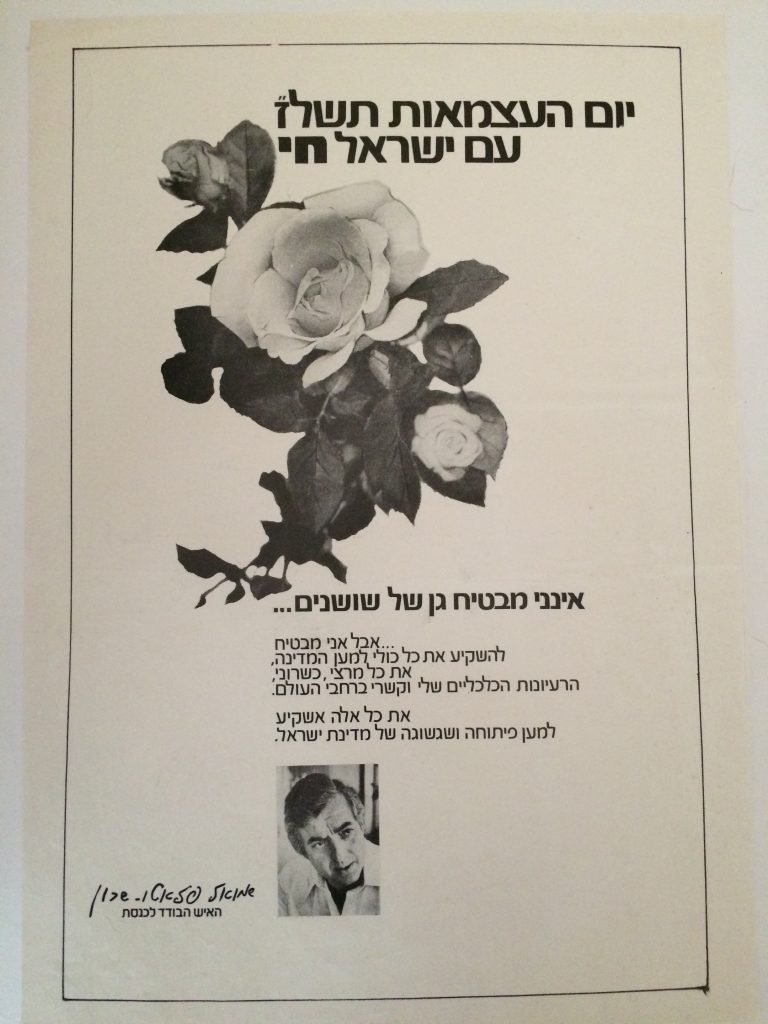

Mrs. Abigal, with her discerning eye, dissected Flatto-Sharon's ad strategy. From strategically placed small ads in unexpected corners to full-page spreads in holiday supplements, she underscored the calculated chaos that Flatto-Sharon orchestrated. She wrote, "In recent days he [Sammy] has been concentrating on two styles: A. The seemingly casual small style ad, scattered in ‘unexpected’ places like… the Money and Economy page in Ma’ariv, where Pay/Shin appeals to audiences who may be interested in ‘my’ economic ideas and connections around the world, especially these days of hysterical tidal wave in the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. That small ad, in the sport section, appeals to the sports’ betting fans, hoping to be confused for a moment by the picture of the Lone Man marching to the Knesset and bet on him. B. The big ad style, which spans an entire page of holiday and Saturday supplements. One solitary picture – an illustration, symbolically, of the briefly expressed idea in the text: a big smiling turtle (‘It's time to move in a different pace!’) Or a fragrant rose (‘I don't promise you a rose garden’). Below the picture – a few lines in which Flatto explains what he knows how to do, a small and unpretentious picture of him, and in the corner below ‘Vote Pay/Shin’. And that's it."

The campaign played on the sympathy garnered from his extradition case, blending myth with reality, she noted. "Pay/Shin has been consciously building on the messes’ affection since the ideal coincidence about his extradition and the natural sympathy of our kind-hearted Don Quixote and scapegoats (pick and choose). With his money he can afford to cultivate any myth that comes to mind. We have the choice of whether to buy or not. But if he intends to succeed in the Knesset as he does in advertising – he might as well try.”

Yuval Elizur, in the Ma’ariv Newspaper article dated April 24, 1977, writes: "Only One Match…," screams one of the giant advertisements for the Ninth Knesset candidate, Samuel Flatto-Sharon. And justice for him, but not necessarily because the same match "would spark new ideas and turn-on hearts with a passion of fresh renewal and fertile creativity," as the millionaire's talented advertisers contended, but because it could ignite the fragile structure of Israeli democracy. And this warning is not only aimed at questioning Flatto-Sharon's innocence from all the heavy charges brought against him in French courts. The impression is that if all the candidates on all the lists were required to prove that they were honest and heartfelt, or even just to give details of their assets and bank accounts’ deposits, many, from the various parties, would decide to quit the election run."

Delving into Flatto-Sharon's method and style, Elizur commended the excellence of the ads. "And in regards to the style of the ads published in the Israeli press. They are actually excellent in their design and caption. They are less insulting and more thought-provoking and planning than the ads of almost all other parties running for this year's election. Whoever examines the ads, from the early ones ‘dedicating’ the ad space as a drawing paper to the children of Israel and announcing that he ‘respects all rival parties who will win the 119 seats in the Knesset’ [Israel has 120 seats all together] will find them highly professional worthy of praises."